Story highlights

About 17% of Gitmo detainees return to terrorist activities, report says

As of last month, the Guantanamo Bay detention facility had 154 detainees

Not everyone at Guantanamo Bay has been found guilty of terrorism

Guantanamo Bay detainees have long been considered America’s most dangerous enemies.

So what happens when they walk free – like the five detainees swapped for U.S. Army Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl?

Do they return to terror activities or transition to quiet, private lives away from the mayhem?

Well, it’s a mixture of both.

How dangerous is this latest swap?

Mathematically, it’s not an even swap. But President Barack Obama’s administration maintains it’s not a risky move for the United States.

The five detainees have been at Guantanamo Bay in Cuba for years, and out of commission for a long time. They probably don’t have extensive networks to tap into, according to two senior U.S. officials.

Additionally, there will be fewer U.S. forces to target in Afghanistan since under a new agreement, most troops will be out of the nation next year.

Qatar has also reassured the United States that it will aggressively monitor the detainees, who will be under a travel ban for one year.

How many freed detainees have returned to terrorism?

At its peak, Guantanamo Bay had 770 men believed by the U.S. government to be involved in terrorist activity or military attacks.

That number has dwindled significantly. As of last month, the facility had 154 detainees.

A September 2013 report from the director of national intelligence reflected on what happened to the roughly 600 people who left Gitmo between its opening in 2002 and July 2013.

Of those, 100 – or 16.6% of the released prisoners – were “confirmed” to have returned “to terrorist activities.” Seventeen of those died, while 27 ended up in custody, according to the DNI report.

An additional 70 are “suspected of reengaging,” it said.

“Based on trends identified during the past 10 years, we assess that if additional detainees are transferred without conditions … some will reengage in terrorist or insurgent activities,” the report said.

Does the U.S. keep an eye on freed detainees?

While the former prisoners are no longer under its control, Washington says it keeps track of them, which is the basis of the DNI report.

During President George W. Bush’s administration, some were handed over to authorities in other countries.

Dozens more were released under Obama.

Are American interests more at risk when they get out?

There are a lot of variables, making this a debatable question.

Except for those accused or convicted of the most heinous crimes such as murder, most people are not detained indefinitely.

And studies show the recidivism rate for those in the U.S. legal system typically top 50% or even 60%, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Armed with that knowledge, the idea of a Gitmo detainee returning to his previous ways may not be surprising.

It also depends on where they go from there.

The DNI report notes the dangers of transferring prisoners to nations with conflicts, instability and active recruitment by terror groups.

In other words, a detainee who returns to a place beset by violence – where terrorist groups and attacks are common – is more likely to return to the fold.

Does this mean the U.S. got a raw deal in Bergdahl’s release?

Depends on whom you ask.

Sen. John McCain, a former prisoner of war, is not popping the Champagne just yet.

He knows a thing or two about life in enemy hands after spending more than five years in captivity in North Vietnam. Since then, he has emerged as one of the nation’s loudest, boldest voices on military matters.

And he feels strongly that the United States did not think this through.

“Don’t trade one person for five (of) the hardest of the hard-core, murdering war criminals who will clearly re-enter the fight and send them to Qatar, of all places,” he told CNN’s Anderson Cooper on Tuesday night.

But White House National Security Adviser Susan Rice defended the Obama administration’s decision.

The “acute urgency” of Bergdahl’s health condition justified the President not notifying Congress beforehand that he was being swapped for the five detainees, she said.

Why are terror suspects held at Guantanamo Bay?

The U.S. naval base there was transformed after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Existing migrant detention facilities were revamped to house detainees of the so-called war on terror.

These were men, who though captured in the battlefield, didn’t fit any detention category. U.S. authorities said they didn’t have the same rights as prisoners of war under the Geneva Conventions. Nor did they have the same rights as those detained within the United States.

The Bush administration argued that since the detainees were not on U.S. soil, they were not covered by the U.S. Constitution. It used that rationale to justify the lack of legal protections for those detained.

That made the base sometimes referred to as Gitmo a sort of no man’s land.

How much does it cost to keep it running?

It costs the Defense Department about $150 million a year to keep the facility in operation.

The U.S. pays Cuba about $4,085 a year for the lease, but the latter hasn’t accepted payment since 1959.

Shortly after his inauguration in 2009, Obama signed an executive order to close the detention facility within one year. It has not happened.

Has everyone at Gitmo been found guilty of terrorism

No.

Peter Bergen, a CNN national security analyst, and Bailey Cahall, a research associate at the New America Foundation, wrote in an op-ed last year that said dozens of detainees cleared for release years ago “remain in seemingly perpetual custody.”

“They have found to be guilty of nothing, yet they are being held indefinitely,” Bergen and Cahall wrote.

“Indefinite detention without charge is a policy that we usually associate with dictatorships, not democracies.”

Bergen also heads the New America Foundation’s International Security Program.

Others, though, view the situation differently. They say terrorists don’t play by any recognized rules of warfare or justice; their mission is to kill, with U.S. forces and citizens as their targets.

McCain says that the five men released as part of the Bergdahl deal could be among those attacking U.S. citizens both at home and overseas.

The five “were judged time after time as unworthy … that needed to be kept in detention because they posed a risk and a threat to the United States of America,” the Arizona Republican said.

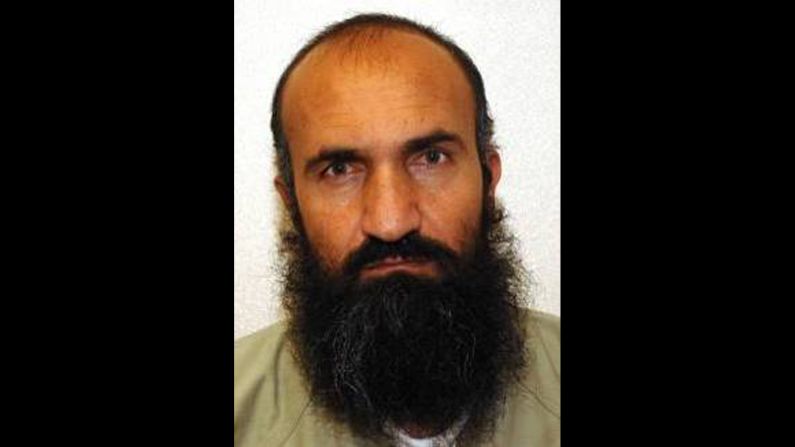

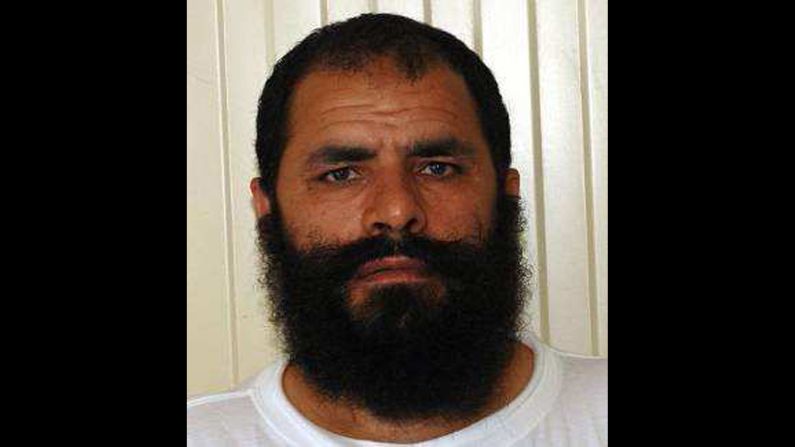

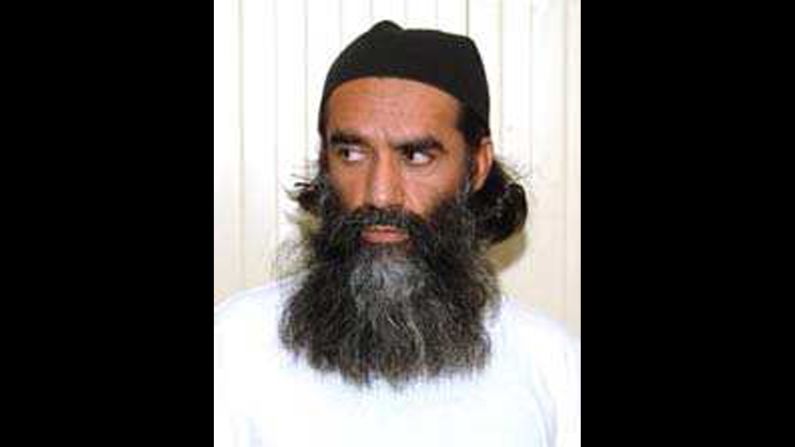

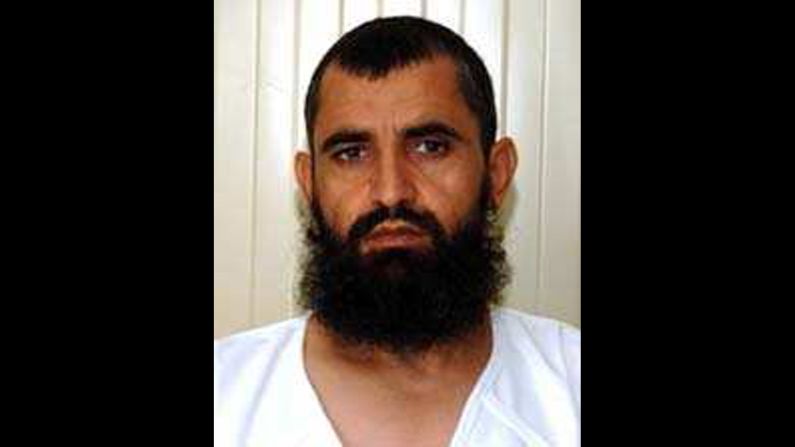

Who were the detainees swapped for Bergdahl?

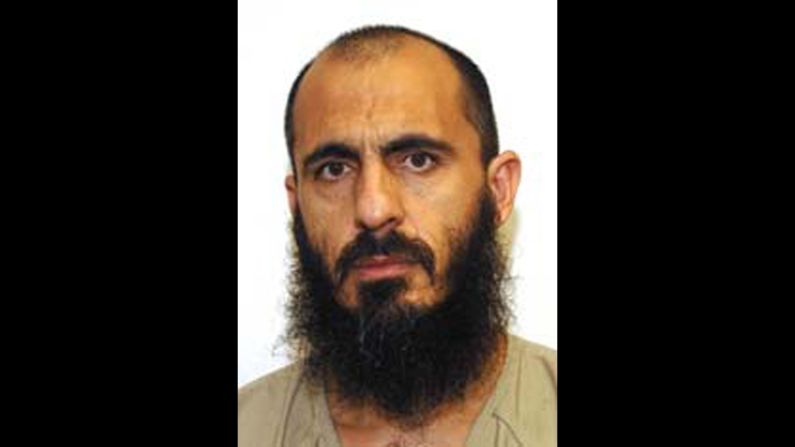

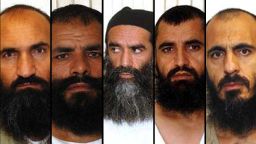

Two senior Obama administration officials identified them as Khair Ulla Said Wali Khairkhwa, Mullah Mohammad Fazl, Mullah Norullah Noori, Abdul Haq Wasiq and Mohammad Nabi Omari.

They were mostly mid- to high-level officials in the Taliban regime who were detained early in the war in Afghanistan because of their positions within the Taliban, not because of ties to al Qaeda.

But some such as Khairkhwa are alleged to have been “directly associated” with Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda’s now-deceased leader in Iraq, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi.