CNN en Español’s Isabel Morales received a fellowship to report this story from the International Center for Journalists.

Story highlights

Despite perils of the desert, many immigrants still risk the journey

Deported immigrants pack a shelter in Mexico, determined to try to cross the border again

With few clues, investigators at an Arizona morgue struggle to identify bodies

Their journey through the desert ended in the back of a U.S. Border Patrol van.

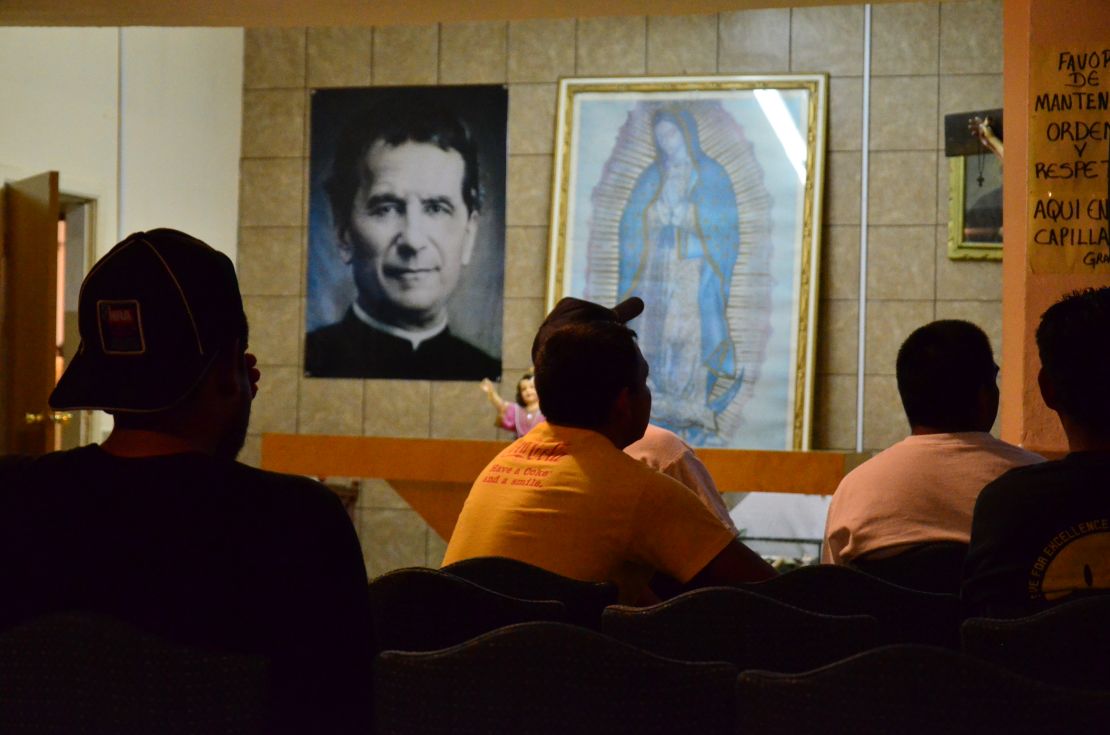

Sitting inside the chapel of the San Juan Bosco shelter for deportees in Nogales, Mexico, Rey and Herlinda rest and wait for another chance to cross illegally into the United States with their children ages 4, 9 and 11 in tow. Temperatures in this stretch of desert that straddles the U.S.-Mexico border hover around 100 degrees.

“I know that I’m putting all three of them at risk, but what else can I do?” said Rey, who says he has lived and worked in the United States without authorization on and off for the past 27 years. Until recently, he kept his family in Mexico, but he says he can no longer afford to sustain two households.

“What’s the motivation? When one of my kids asks for meat or (candy), I cannot just say no,” Rey added. “Mexico never changes. There was poverty when I left in 1986 and nothing has changed.”

The deadliest trip in America?

The hundreds of thousands of immigrants like Rey and Herlinda have tried to cross illegally into the United States over the past two years, even as the government steps up investments in manpower and technology to secure the nation’s borders.

More than 150 end up dead every year. Thousands more get deported every month, according to U.S. Customs and Border and Protection figures. But would-be immigrants keep coming.

“People are still driven by economic necessity to come to the United States by whatever means they can. Some come to join family members already here, others because they are hungry,” said Isabel Garcia, a public defender and a co-chair of the Tucson, Arizona-based Coalition for Human Rights.

“But the fact is that very few are prepared for such a hard trip. Many have to survive days and days in the desert,” she said, “and they can never carry enough water.”

Some make it past the desert and go on to find jobs in the United States. But on the Mexican side of the border, deportations from the United States have become so common that shelters and businesses have opened up, catering to people who’ve gotten kicked out of the United States.

Others come back bruised, robbed by smugglers or worse, says Hilda Irene Loureiro, a Mexican merchant who runs the shelter.

Loureiro says she opened up the San Juan Bosco shelter after seeing deportees huddle in the back of her shop which is located just a few blocks from the fence that divides her city from Nogales, Arizona. She decided to build a place for them to spend a few days in safety.

Dozens of migrants arrive each day at her shelter for food and a chance to sleep on a soft mattress. Most of the time, she says, they leave not to go back to their homes, but to try and cross into the United States again.

“They come here from all over Mexico, but now there are lots Central Americans looking to leave their countries,” she said.

The shelter houses more than 50,000 migrants each year. They can stay for up to three days, free of charge. Its three sleeping areas house 145 bunks, but on any given night up to 360 migrants stay there, finding room to sleep on the floor of the dining room or the chapel.

Portraits of saints and other religious icon fill the chapel, where travelers say their prayers before chancing the desert again.

As the national debate over immigration reform heats up, border security is a top issue on many lawmakers’ agendas.

But from her point of view at the border, Loureiro says she doesn’t think any efforts in Washington to boost border security will have much of an impact on whether people make the dangerous journey.

“The migrants are going to continue trying to get to the other side of the border no matter what. They will do this regardless of danger or consequence,” Loureiro said. “They will do it because they lack economic opportunities in Mexico and they lack the education and (job) skills to get ahead.”

According to the office of U.S. Customs and Border Protection, in fiscal year 2013 a total of 414,397 undocumented immigrants were apprehended after crossing the border illegally into the United States. The previous year, the figure was 356,873.

Arizona desert: Gateway to dreams or graveyard?

For those who make it across the border, it isn’t an easy journey. Thousands of would-be immigrants have died in the desert of southern Arizona in the past 10 years, according to the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office. Most of them die after suffering dehydration in the summer or fall to hypothermia in the winter.

The trek can often last days, as smugglers take them through remote paths in order to avoid detection by the Border Patrol. Wild animals roam the area at night and the people the migrants paid to get them safely across often turn on them, robbing them of their money and abusing the women before abandoning them, according to authorities.

“Many fall into the abuses of the smugglers, sexual abuse,” said Manuel Padilla, head of the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector. “The only thing that matters to them is money, not people.”

Padilla said Border Patrol agents often spot and rescue immigrants stranded in the desert, which is an important part of the agency’s job. However, the agency also focuses on prevention, by educating would-be immigrants of the dangers involved in trying to cross the border illegally.

They ask foreign diplomats at consulates in the United States to spread the word in their countries about the dangers of illegal border crossings, and they try to get the word out in Spanish-language media, Padilla said.

Even so, the phenomenon of deaths in the desert has become so bad that one group of investigators labeled it a “humanitarian crisis at the border.”

According to the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office, in 2012 the bodies of 157 migrants were recovered in the desert. In 2013, the remains of 169 people were found there.

“Since 2001 we’ve had around 2,200 immigrant deaths,” most of them Mexican citizens, said Gregory Hess, the Pima County medical examiner. “When we find only a bone in the desert, a femur … or an arm, it’s not here for long… we take photographs and measurements and DNA” samples.

Unclaimed bodies and bones are buried or cremated after about a year, he said.

Searching for clues

Since a majority of the bodies belong to Mexican citizens, morgue staff are in regular contact with the Mexican Consulate in Tucson.

It isn’t the job Jeronimo Garcia thought he was signing up for when he joined the Mexican Foreign Service. But now he’s become so used to handling human remains that he no longer feels the need to wear a surgical mask to protect himself from the stench of death.

The consulate employee has become a go-to person for American authorities when it comes to finding clues about the immigrants’ identities.

Garcia has earned the trust of U.S. officials because of his track record over the past 12 years, helping to identify dozens of bodies.

“(This one) has dental work. Sometimes teeth give us clues as to where they come from,” Garcia said as he examined cadavers and bones at the Pima County morgue. “Central Americans, particularly Guatemalans, often have ornamental work done. They put copper stars on their teeth.”

Migrants sometimes sew documents into their underclothes, or conceal strips of paper with the telephone number of a contact in the United States or their country of origin, he says. This information can be a solid clue to track down identity.

After the extensive search at the morgue, the bodies are labeled and stored in a freezer. Personal effects and identifications are also stored, as any clue could lead to the identification of a cadaver.

Sometimes, there aren’t many clues. If all that Garcia and the medical examiner’s office have to go on is a set of dry bones, DNA testing is the only viable option.

The Mexican Consulate sometimes pays for the tests when Mexican citizens are involved.

For immigrants from other countries, the medical examiner’s office relies on its growing ties with the New York-based Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team.

The organization, which started out trying to identify remains of dissidents killed during Argentina’s brutal military dictatorship, now has also collected more than 1,700 DNA samples from families in Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, Costa Rica and Guatemala in efforts to help find missing migrants. So far, they’ve identified 65 bodies.

“This is never a happy ending. … We just try to reduce the time that families have to prolong their pain,” said Mercedes Doretti, who directs the organization. “What it means is ending the uncertainty of the family not knowing what happened to their relative, the suffering that everyone goes through.”

Journalist Julian Resendiz contributed to this report.