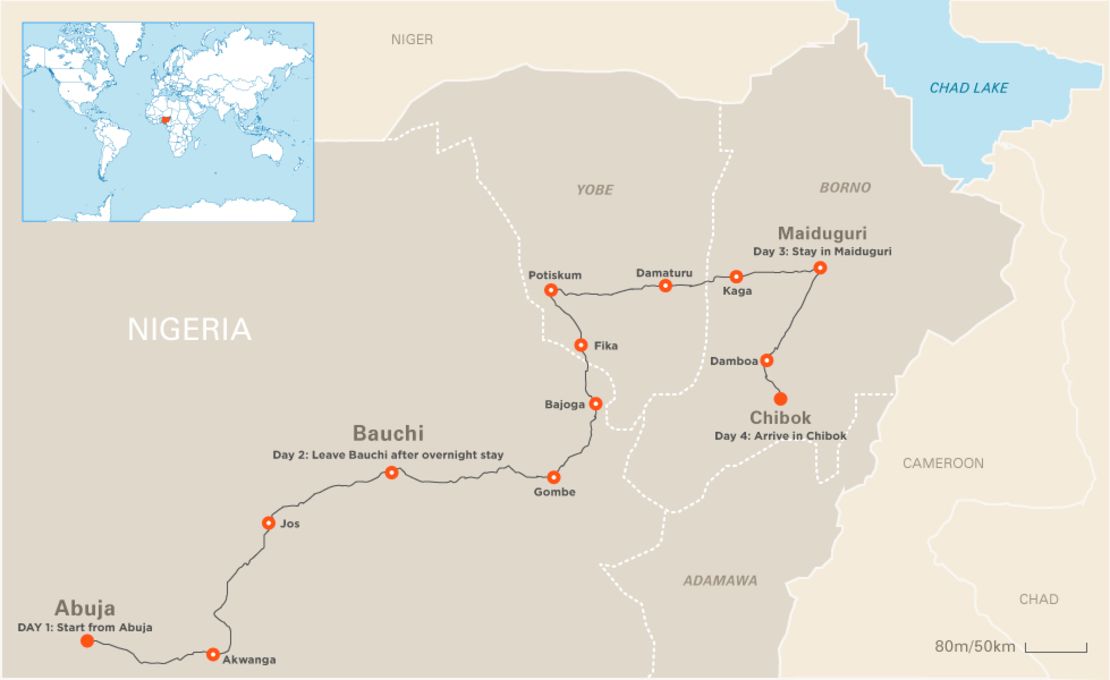

Editor’s Note: CNN’s Nima Elbagir, Lillian Leposo and Nick Migwe made the dangerous journey to Chibok, Nigeria, to gather firsthand accounts of the abduction of more than 200 schoolgirls – and how people in the northeastern town are living in fear.

Story highlights

On April 14, Boko Haram militants abducted more than 200 girls from a school in Nigeria

The schoolgirls had been sleeping at the school in Chibok, in northeastern Borno State

Producer Lillian Leposo was part of a CNN team that spent four days traveling to the village

They passed numerous checkpoints until the final 45 minute leg to Chibok itself

Ahead of the rain-lashed vehicles, tree branches lay across the road. We’d encountered countless military, police and vigilante checkpoints but now we were in Boko Haram’s backyard, we worried if the checkpoints were being replaced by ambushes.

After the kidnapping of more than 200 schoolgirls from a school in northern Nigeria, the whole world’s attention was focused on one village - Chibok – but CNN was the first news organization to send a team to the scene of the atrocity.

Setting up interviews with those impacted by the mass abduction was quite a task, but once in place, the bigger challenge became “how do we safely get there.” I have covered conflict zones before and always focus on the stories we’ll hope to get, rather than the potential danger. That’s how I deal with the fear.

We were trying to find security escorts, but no one was willing to journey to Chibok, which is situated in Borno State – one of the three states considered to be the heartland of Boko Haram.

The militant Islamist group has bombed schools, churches and mosques; kidnapped women and children; and assassinated politicians and religious leaders. It was unlikely they would welcome Western journalists, and those accompanying us, with open arms.

The journey from the relative safety of Nigeria’s capital, Abuja, to the remote countryside stalked by Boko Haram can take 8 to 10 hours, but logistics and security concerns meant that it took us four days.

We traveled in two cars – 4x4s to handle the terrain.

Even before we reached the militant-plagued area, we suffered setbacks. In Bauchi State, a tire on the first car blew-out, causing it to lose control.

Now we were down one car. It was hours before we could find a resident willing to lend his rundown car to us and to travel to Chibok. Eventually this car broke down and had to be abandoned.

‘Why did I come?’

When we entered Borno State, we were hit by a violent storm.

We could see absolutely nothing as strong rains lashed our vehicles. Night had fallen, we were still far away from our destination of the state capital Maiduguri and our driver was unfamiliar with the road. We couldn’t see to the side, behind or ahead.

While covering stories in other conflict zones, there have been instances when the danger was so apparent that I wondered - “Why did I come?” For this story, it was that night as we entered Borno State – in the dark during a strong storm.

The situation was all the more eerie because the storm had brought down branches across the road and we wondered if we were being set up for an ambush.

Eventually, however, we did arrive in the relative safety of Maiduguri, the state’s capital, only to encounter another hurdle.

We had organized a police escort to accompany us for the final, most dangerous leg from Maiduguri south to Chibok. The road is notorious for ambushes and attacks by Boko Haram.

As we readied to journey along it on our third day, our police escort said they could not take us because that morning it had been the scene of a shootout between the militants – who had come from raiding a village - and security forces. One of the officials had been shot in the neck.

Beyond the checkpoints

By the time we left with a police escort the following day, it was about noon.

Our route had all been tarmac until the town of Damboa, from where the road leads to Chibok.

From that point, there’s no tarmac whatsoever. Drivers are forced to swerve left and right to avoid the potholes caused by the heat and it’s really rough terrain – savannah.

Damboa also hosted the last security checkpoint we encountered.

Prior to that we had been forced to stop constantly. There would be a military checkpoint, a few minutes later a police checkpoint and then a few minutes later a vigilante checkpoint – staffed by local men armed with machetes looking out for Boko Haram.

But on the road to the village now the focus of the whole world’s attention because of the atrocity that took place there – there was nothing, not one checkpoint.

We were driving through a vast area of open land, high grass and shrubs. And there was no homestead in sight. Any checkpoint set up by the security forces would basically make them sitting ducks for the insurgents.

Our convoy was on its own.

Our police escorts were armed with AK-47 rifles and we had flak jackets on the seats beside us – kept out of sight so as not to raise questions about our purpose – but our main defense was to drive as fast as possible along the pitted road for the 45-minute journey.

A number of thoughts went through my mind; this was the road to Chibok; militants could storm us from anywhere on that road.

It was a very scary moment. And at the same time I kept thinking, “how is it possible that there is no single security check point towards this village? Not even one?”

Arriving in Chibok we found a spread-out village with a vibrant market with residents buying and selling food stuffs. The most popular stand, however, is the phone charging stand - because there is no power in the homes.

Overnight stay

Our late departure meant we had arrived in Chibok around 3pm and the police said it was too dangerous to return along the same road so we had to sleep over in the village. That wasn’t part of the plan. Ever.

We were offered guest huts to stay in. But we declined as our presence would be so obvious – and of course we didn’t want to be with the police because if there was an attack that would be where a shootout would be.

A very brave local family hosted us, providing us with mats to sleep outside. A village that has lost so much still found reserves of humanity to offer us hospitality.

During the day, Chibok looks like a normal village. But at night is when you see the fear and terror. The women, elderly and children go to sleep. And the young men stay awake, doing patrols, keeping vigil.

CNN’s team joined them, and discovered that one thing was clear: Chibok residents have stopped waiting for the government, they are protecting their own.

See Nima Elbagir’s report on the Chibok night patrol.

See Nima Elbagir’s report on a Nigerian girl who escaped Boko Haram.