Story highlights

An Australian navy ship is expected to keep searching a small area into Tuesday

It is trying to regain a signal that it picked up Sunday that could be from Flight 370

If it detects the pings again, it will deploy an underwater vehicle that can look for wreckage

Without a new signal, the possible area will be larger and take longer to search

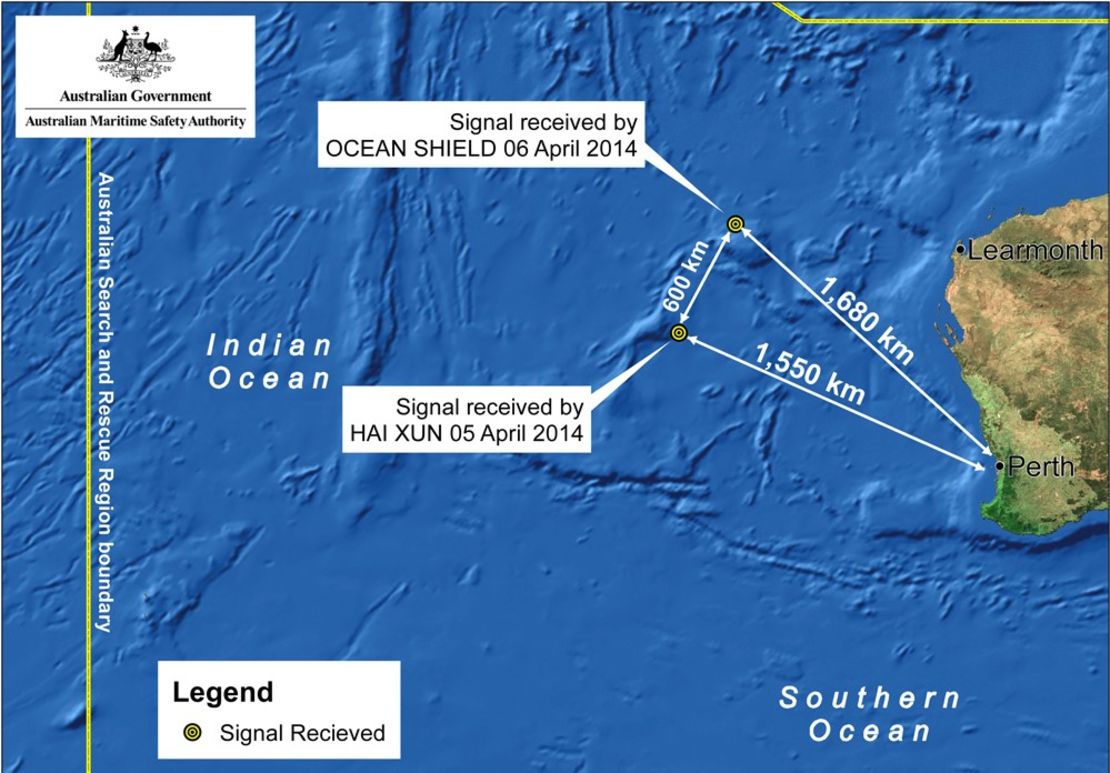

The pings detected by the crew aboard an Australian navy ship in the southern Indian Ocean have given those searching for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 renewed hopes of finding the missing plane.

Australian officials leading the search said the signals picked up Sunday were consistent with those transmitted by an aircraft’s flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder.

But the officials warned that they still need further evidence, such as a visual sighting of wreckage on the seafloor.

“There are many steps yet before these detections can be positively verified as being from missing Flight MH370,” Angus Houston, the head of the Australian agency coordinating search operations, said Monday.

Here’s an explanation of what the next phases are in the underwater hunt for traces of the passenger jet.

Do searchers have enough pings to figure out where they’re coming from?

No, not yet.

The Ocean Shield, an Australian navy ship that’s slowly towing a pinger locator through the water, is going back and forth over the area where it twice picked up a signal Sunday.

“The focus is on trying to reacquire the acoustic signal they had 24 hours ago,” said Commodore Peter Leavy, who is coordinating military contributions to the search.

As of Monday morning, the high-tech pinger locator, supplied by the U.S. Navy, hadn’t redetected the pings, officials said.

“Probably for the next 24 hours, Ocean Shield will continue its runs back and forth over the area,” Houston said.

Why is it crisscrossing the same area?

The aim is to use triangulation to pinpoint the location of whatever is transmitting the pings, according to Cmdr. William Marks of the U.S. 7th Fleet. “For us in the Navy, this is kind of our bread and butter,” he told CNN.

The crew of the ship does this by towing the pinger locator along a series of intersecting lines across a relatively small area of ocean.

If the sound is picked up along three different lines that cross at the same point, “that’s a pretty positive indication of where the signal’s coming from,” Marks said.

But it’s a slow and painstaking business. By the end of its runs Tuesday, Ocean Shield expects to have thoroughly covered only a 3-mile-by-3-mile box, according to Leavy.

Each run across the area takes the ship seven to eight hours. That’s because it’s moving slowly – at about 3 knots (3.5 mph) – and because turning around with the huge length of cable that’s dragging the pinger locator through the ocean depths is a delicate, drawn-out process.

What happens if they pick up another signal in that area?

At that point, they will deploy an unmanned underwater vehicle that’s on board the Ocean Shield, the Bluefin-21. The vehicle, also from the United States, is able to generate maps of the bottom of the ocean and “determine if there’s something unusual on the seafloor, like aircraft wreckage,” said Houston.

“In the event of finding something unusual, the autonomous vehicle will come back to the surface and will then be fitted with a camera,” he said. “And hopefully, we would then be able to pick up imagery.”

But one potential problem is that the water in the area the Ocean Shield is searching is about 4,500 meters (14,800 feet) deep, the limit of the Bluefin’s range.

“We’re right on the edge of capability,” Houston said.

If the area of the seabed where the pings are coming from is any deeper, then the search crews would need remotely operated vehicles that can go even farther down. Houston said officials are looking into what other vehicles could be deployed, if needed.

What if they don’t pick up another signal?

If the pings the Ocean Shield’s crew have detected are from Flight 370, they could cease at any moment. The batteries powering the locator beacons on the missing plane’s flight recorders could already have expired. At the very most, they could last another week or so.

Without another signal, the members of the search team will have to take a look at what information they have been able to gather.

“If we’re unable to fix the location, the people who are out there have to do an analysis of everything they’ve got and make an assessment of whether they would deploy the underwater vehicle in the most likely area,” Houston said.

“I would anticipate that’s what will happen: The underwater vehicle will be deployed and continue the work,” he said.

But that would mean searchers have far less precision than they would hope to have when searching waters so deep.

“If we have a large area of uncertainty, it will take several days to actually cover what would appear to be a fairly small area,” Houston said. “Things happen very slowly at the depths we’re dealing with.”

READ: Timeline: Leads in the hunt for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 weave drama

READ: Lucrative China-Malaysia relations not derailed by search for MH370

READ: Wife of Flight 370 passenger: ‘I needed to know they were looking for Pauly’