Story highlights

Street art campaign "Stop Telling Women to Smile" aims to deter street harassment

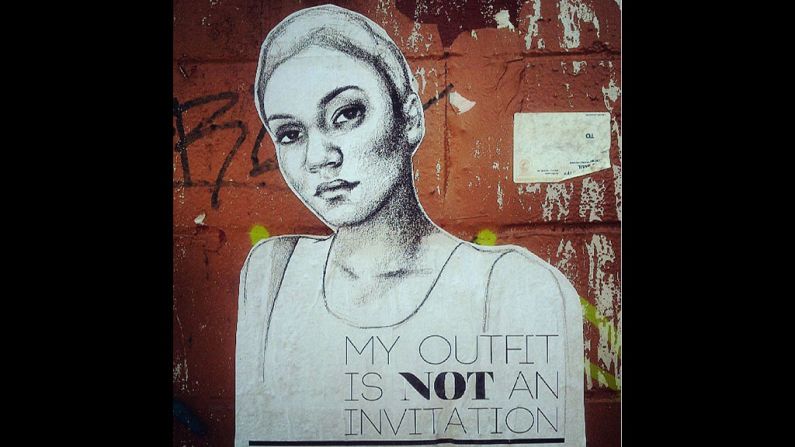

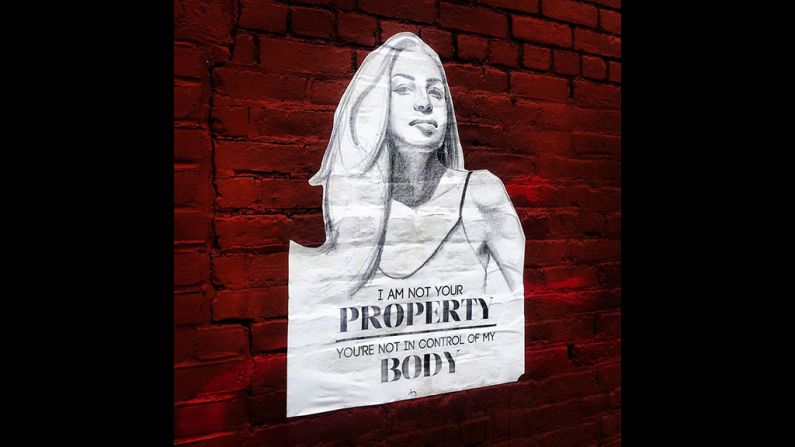

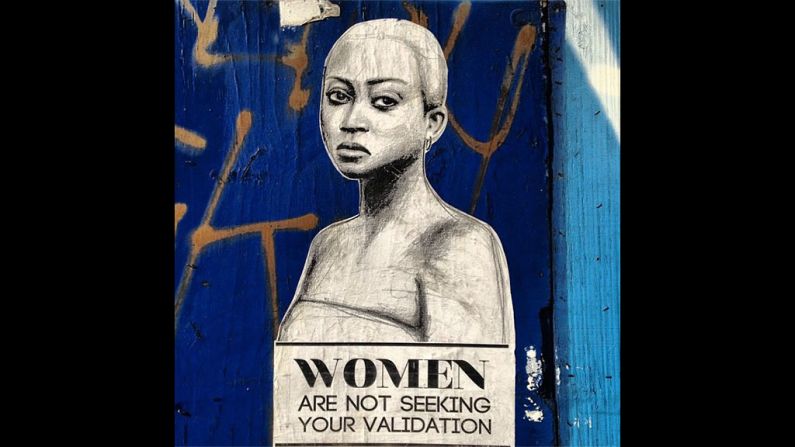

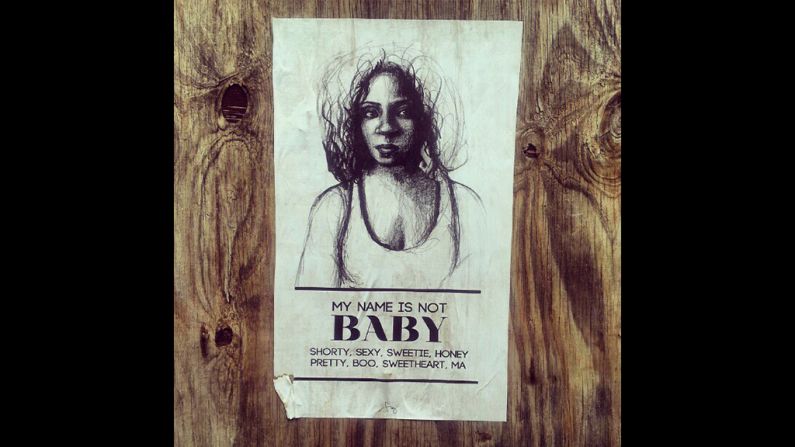

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh sketches portraits with anti-harassment messages

People plastered her posters in their communities for International Anti-Street Hasrassment Week

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh had never heard of the term “street harassment” until two years ago. Before then, she simply considered the hisses and catcalls from strangers in the street an “annoying part of everyday life” that came with being a female.

Now, street harassment is the focus of an ongoing art project led by Fazlalizadeh that’s drawing global attention. This weekend,as part of International Anti-Street Harassment Week, people from the United States to Australia plastered communities with portraits from Fazlalizadeh’s “Stop Telling Women to Smile” series.

Named for a self-portrait of Fazlalizadeh with the message “Stop Telling Women to Smile,” the formidable portraits include sentiments meant to deter street harassment. One piece tells viewers,“You can keep your thoughts on my body to yourself”; another reads “Women don’t owe you anything.”

Fazlalizadeh has spent the past year and a half traveling the country speaking to women and creating new posters based on their experiences of gender-based street harassment.

Her initial goal was to find out how women experience street harassment differently depending on where they live. Women in car-dependent cities described getting calls from men in cars. In cities like New York, Washington and Chicago, women reported men groping or leering at them on public transportation.

What seems to be universal is the impact, Fazlalizadeh said. It leaves women feeling vulnerable and unsafe in their communities, as if their sole purpose in leaving the house each day is to entertain men. It makes women think twice about what they wear, the routes they take, even their body language.

“The way that it affects women and things they go through have pretty much the same theme: Women are out for consumption and for your enjoyment,” Fazlalizadeh told CNN. “It creates a sexually hostile climate in our streets and communities.”

Since she started out papering the streets of Brooklyn in 2012, Fazlalizadeh has forged partnerships with community-based nonprofits and advocacy groups to create and share her work. She works with them to arrange talks with women and get permission from property owners to post her work on walls or in public spaces. She encouraged people who participated in Friday’s global poster-pasting night to act within the bounds of the law.

For Anti-Street Harassment Week, Fazlalizadeh put up posters in Atlanta with members of the community. In a talk at Georgia State University earlier in the week, she told a standing room only audience of men and women about the range of responses to the portraits. She receives mostly positive feedback from people in person; the posters in public, however, bear the brunt of criticism.

Sometimes, people scribble derogatory words and phrases on her posters. Other times, she has seen handwritten exchanges on the posters debating its message, like a real-world message board.

That’s great, she says, because that’s what the project aims to do: inspire discussion and hopefully collaboration among the sexes.

Occasionally, a well-meaning man asks her in person about the idea of intention: What if he doesn’t intend to harass or make a women feel uncomfortable? What if he just wants to compliment a woman in the hopes of getting her attention? Surely, that’s not harassment.

Fazlalizadeh understands where he’s coming from, and she respects him for engaging her in discussion, she said. But what matters is how it makes the woman feel, she said.

“That’s where all I can say is, ‘I’m sorry, I don’t agree with you,’” she said, prompting laughter from the audience.

“That’s where social norms and taking cues are important,” she said. “But the main goal is to make us rethink what’s considered normal and acceptable treatment of women.”