Story highlights

Rwandan genocide took place 20 years ago: Hutu militia massacred members of the Tutsi ethnic minority

Many of those who survived the carnage were left scarred; rape was used as a weapon, spreading HIV

Marie Jeanne's daughter Kirezi was born as a result of rape; two decades on this still pains both of them

But Kirezi is determined to dream of a brighter future for herself and her country

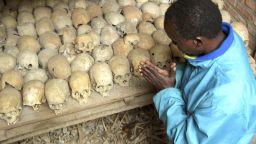

Every year, beginning in April, Rwanda’s government urges its citizens to “Kwibuka” – the Rwandan word for “remember.” To remember the hundreds of thousands of lives lost during the country’s 1994 genocide.

But all Marie Jeanne wants to do is to forget.

The 36-year-old’s entire family was slaughtered during that dark period in her small East African country’s history.

The massacre saw Hutu militias and civilians alike murder vast numbers of members of the Tutsi ethnic minority: Men, women and children, many of whom had been their neighbors before the conflict began.

The killings finally came to an end 100 days later, when Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) troops, led by Paul Kagame, defeated the Hutu rebels and took control of the country.

To Marie Jeanne the end of the war also meant an end to the repeated, brutal rapes she had been forced to endure at the hands of many different men.

“Wherever we used to go and meet a roadblock at least two would rape you and release you,” she tells CNN. “Some could let you go and others would hold you for longer.”

The genocide left Marie Jeanne emotionally and physically scarred, HIV+ and pregnant. She was just 16 years old.

Community members gave her shelter and she says some of the women told her they would help her with the abortion she so desperately requested.

But as time passed, she knew they had lied to her. Then, the labor pains came.

Marie Jeanne says it was some time before she could finally look at her newborn baby girl, who she named Kirezi.

And 20 years on, Marie Jeanne says her daughter’s birthday is still a source of pain to her.

“I never remember the birthday of my child because there was nothing good about it,” she says. “I have never celebrated her birthday because most of the times I never want to remember it.”

Kirezi mirrors her mother’s pain. Seated on a wooden chair in their small living room, she fiddles with a bead bracelet on her wrist. Her lips tremble as she tries to bare her soul to us. Her anguish is palpable.

“I was born going through all bad things, so I feel that I don’t really care about my birthday. Birthdays are for people who are happy only,” she says.

“It’s painful - it hurts me, I always ask myself and I lose all my courage. I ask myself why I existed. And ask myself why it happened. And I feel that I am not worth anything. It makes me so sad,” she cries.

Marie Jeanne says she loves her daughter and would do anything for her, but at times she feels that her daughter is a constant, painful reminder of the horrors she went through two decades ago.

“Within thirty minutes my heart can change and I feel bad against her in my heart,” she says. “Whenever I see her, I remember so many things.”

Marie Jeanne unscrews a plastic bottle containing anti-retroviral tablets (ARVs). The medicine, taken twice daily, is helping her stave off the worst symptoms of HIV/AIDS. For now.

“During the genocide, the militia deliberately infected women with HIV,” Odette Kayirere, co-ordinator at the Association of the Widows of Rwanda (AVEGA), explains.

At the AVEGA headquarters in Kigali, genocide survivors with HIV/AIDS line up to receive ARVs.

Most have similar stories to Marie Jeanne. Passed on from attacker to attacker, they contracted the AIDS virus. For them, this is the legacy of the genocide.

“It was a plan,” says Marie Jeanne. “Their aim was to make genocide carry on.”

But Kirezi is determined to unchain herself from the dark past. Instead she dreams of a brighter future.

“I want to be a very important person,” she says. “To help people in similar situations as me, vulnerable people like orphans, and also to be a minister.”