Story highlights

- U.S. has had alliance with Saudi Arabia since 1945; Obama met King Abudullah Friday

- Peter Bergen says the relationship is now at its lowest point

- Saudis are upset that Obama didn't stand by the "red line" he drew on Syria

- Bergen: Two nations share common ground in opposing al Qaeda's rise in Syria

The world's most powerful democracy and the world's most absolute monarchy have long been close, if unlikely, allies.

They are bound together by common interests -- the free flow of oil and, more recently, fighting al Qaeda.

That alliance was first sealed between President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Saudi King Adul Aziz on February 14, 1945, when they met on the deck of the USS Quincy as the American warship cruised in the Suez Canal.

FDR and his advisors knew that oil, of which Saudi Arabia was well endowed, was a key component of America's economy. Indeed, Standard Oil of California had signed a farsighted deal a decade earlier giving it exclusive production rights in Saudi Arabia.

Thomas Lippman, who has written authoritatively on U.S.-Saudi relations, writes that as result of the meeting on the Quincy, the American president gave the Saudi king a DC-3 airplane that was specially outfitted with a rotating throne that allowed the king always to face the holy site of Mecca while he was in the air.

For his part, King Abdul Aziz so enjoyed his meals as the president's guest on board the Quincy that he surprised his host with an unusual demand: he wanted to take the Quincy's cook for himself. FDR was able to diplomatically ward off this request. (The concept that human beings are not personal property came to the Saudi kingdom relatively late; slavery was only abolished there in 1962.)

For more than six decades after that important meeting on the Quincy the Saudi-American relationship has largely worked well for both countries. Saudi Arabia is the world's largest oil producer and sits on around a fifth of the world's proven oil reserves and therefore it can set oil prices by increasing or lowering oil production. Generally it has done so in ways that respect American interests.

When the Saudis really needed the States following Saddam Hussein's 1990 invasion of their neighbor Kuwait, the United States sent a half a million troops to the Gulf to expel Saddam's forces.

The news that 15 of the 19 9/11 hijackers were Saudis certainly put something of a dent in the U.S.-Saudi alliance, but the George W. Bush administration had close ties to the Saudis and matters were soon smoothed over, particularly after 2003 when al Qaeda began staging attacks on Westerners and oil facilities in the Saudi kingdom, at which point the Saudis launched an effective crackdown on the group.

Yet today, the Saudi-American alliance has never been in worse shape.

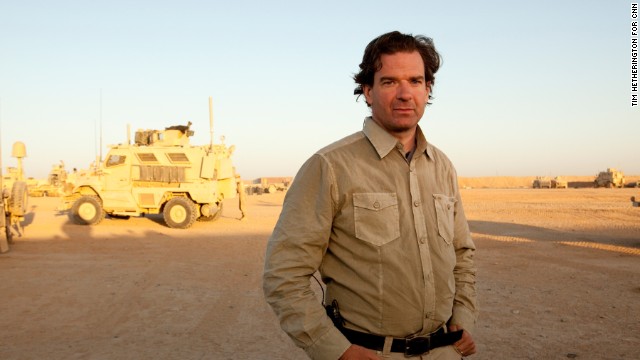

That is why on Friday President Barack Obama met with Saudi King Abdullah, one of the sons of King Abdul Aziz, in an attempt to patch things up.

What went wrong? In recent months the normally hyper-discreet Saudis have gone on the record about their dissatisfactions with the Obama administration.

In December, Prince Turki al-Faisal, the former Saudi intelligence chief and ambassador to Washington, took the highly unusual step of publicly criticizing the administration, "We've seen several red lines put forward by the president, which went along and became pinkish as time grew, and eventually ended up completely white...When that kind of assurance comes from a leader of a country like the United States, we expect him to stand by it."

It's inconceivable that Prince Turki, whose brother is the Saudi foreign minister, would make these public comments without approval from the highest levels of the Saudi government.

Why are the Saudis going public with their dissatisfaction with the Obama administration? The laundry list of Saudi complaints most recently is that the United States didn't make good on its "red line" threat to take action against the Bashar al Assad regime in Syria following its use of chemical weapons against its own population.

Syria is a close ally of Saudi Arabia's archrival, Iran, and the Saudis are also growing apprehensive that the United States will not take a firm line on Iran's nuclear program -- which the Saudis see as an almost-existential threat -- now that the U.S.-Iranian relations have recently thawed.

The Saudi were also puzzled by the fact that the Obama administration seemed willing to let a longtime U.S. ally, Egyptian dictator Hosni Mubarak, be thrown overboard during the "Arab Spring" of early 2011. What did that say about other longtime U.S. allies in the region?

(Interestingly, these list of gripes look quite similar to those of another powerful player in the Middle East -- Israel.)

Prince Mohammed bin Nayef, the powerful Saudi Minister of Interior, was in Washington last month. According to a senior Saudi official his discussions in Washington ahead of Obama's trip were all about Syria.

Here Washington and Riyadh have a real common interest; preventing the rise of al Qaeda in Syria.

Saudi Arabia made it a crime last month for its citizens to travel to fight in overseas conflicts such as the Syrian civil war. Those Saudis who have gone to fight in Syria often join al-Qaeda-aligned groups.

Some 1,200 Saudis have traveled to Syria, of whom 220 have returned to the kingdom, according to the senior Saudi official. There is great concern in the kingdom about potential "blowback" caused by such militants who have obtained battlefield experience in Syria.

Both the United States and Saudi Arabia have an interest in blocking al Qaeda's growth in Syria.

Obama and King Abdullah met on Friday outside Riyadh. After the meeting, a senior US official said that the United States and Saudi Arabia remain "very much aligned" despite recent policy differences over issues like Iran.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.