Story highlights

A new study identifies CTE in soccer and rugby players

CTE can develop from repeated blows to the head

The research raises questions about "heading" in soccer

The disease that carves an insidious path through the brain seems to be doing the same through sports.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, the degenerative brain disease associated with concussions, has been identified in both a soccer and a rugby player, according to a review in the journal Acta Neuropathologica.

The brain tissue of people found to have CTE displays an abnormal build-up of tau – a protein that, when it spills out of cells, can choke off, or disable, neural pathways controlling things like memory, judgment and fear. CTE can be diagnosed only after death.

According to Dr. Ann McKee, a neuropathologist who has examined dozens of brains found to have CTE, the brain of the soccer player – Patrick Grange – displayed diffuse disease.

“There was very severe degeneration of the frontal lobes with widespread tau pathology in the frontal, temporal and parietal lobes,” McKee, director of neuropathology at the Bedford VA Medical Center, said in an e-mail. “He is one of the youngest players to have shown this much disease.”

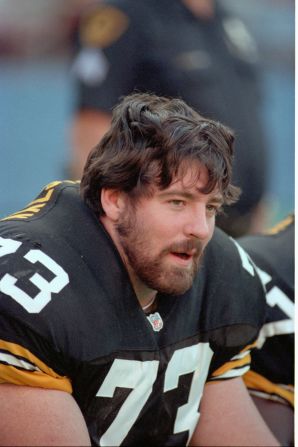

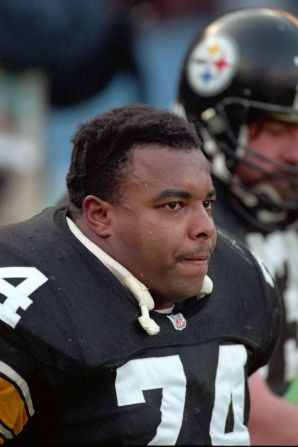

Former NFLer: ‘Your mind just goes crazy’

Grange played with the Chicago Fire Reserve MLS team and the Albuquerque Asylum semi-pro team, according to his obituary. He died in 2012 at 29 after being diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, a rare, incurable neurodegenerative disease. About 13% of the 103 CTE cases uncovered by McKee and colleagues also showed evidence of progressive motor neuron disease.

“(Grange) had no known genetic predisposition for ALS,” said McKee, professor of neurology and pathology at the Boston University School of Medicine. “And no family members have been diagnosed with ALS.”

An autopsy showed that Grange had Stage 2 CTE with motor neuron disease, according to a statement from Boston University.

His case is interesting because it raises questions about the relationship between heading the ball and CTE.

“The fact that Patrick Grange was a prolific header is important,” Chris Nowinski, co-founder and executive director of the Sports Legacy Institute, said in an e-mail. “We need a larger discussion around at what age we introduce headers, and how we set limits to exposure once it is introduced.”

Heading would seem to be innocuous compared with the brutal hits that can be dealt in a football or hockey game, but the damage, according to studies, can add up. Headers in soccer are associated with microstructural damage to brain tissue and memory problems; and an Italian study linked them with ALS.

Similarly, researchers found Australian rugby union player Barry “Tizza” Taylor died in 2013 of complications of severe CTE with dementia at age 77. Taylor played for 19 years in amateur and senior leagues before becoming a coach, according to Boston University.

“Cognitive problems, memory loss, attention difficulties and executive dysfunction were first noted in his mid-50s, followed by depression and anxiety, worsening explosivity and impulsivity,” the statement said. By his mid-60s, the statement said, Taylor was “physically and verbally abusive” and “paranoid.”

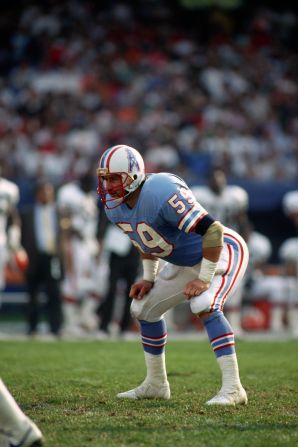

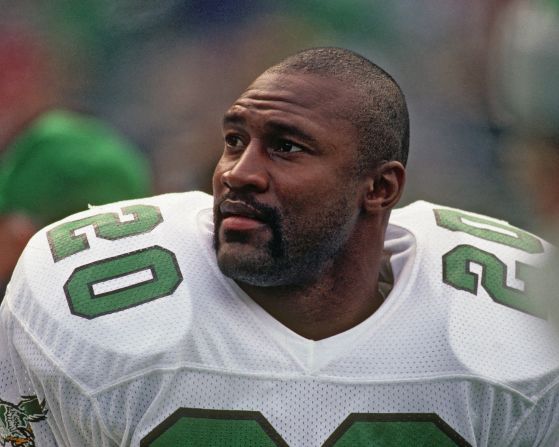

Tony Dorsett: ‘I’m going to beat this’

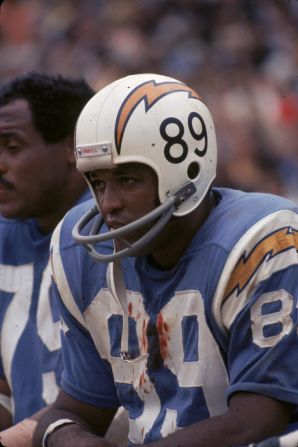

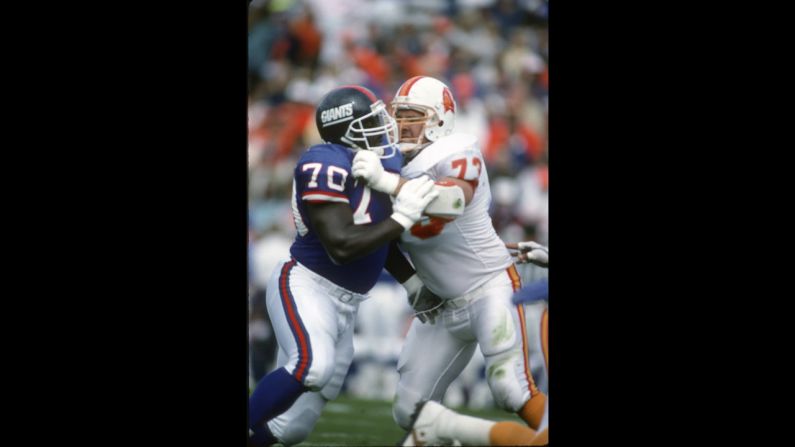

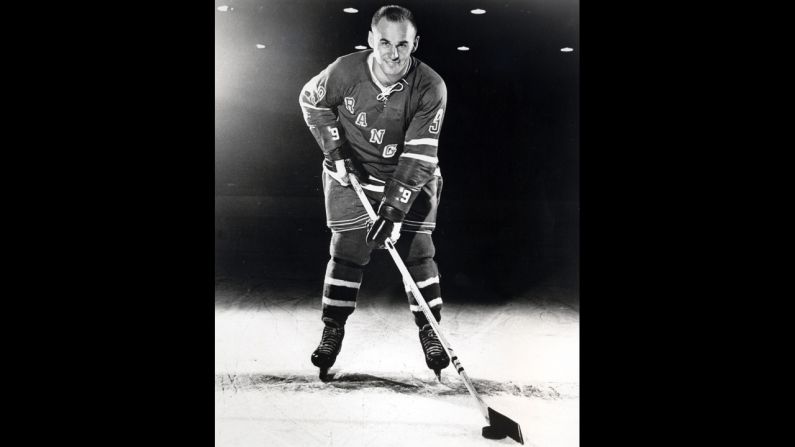

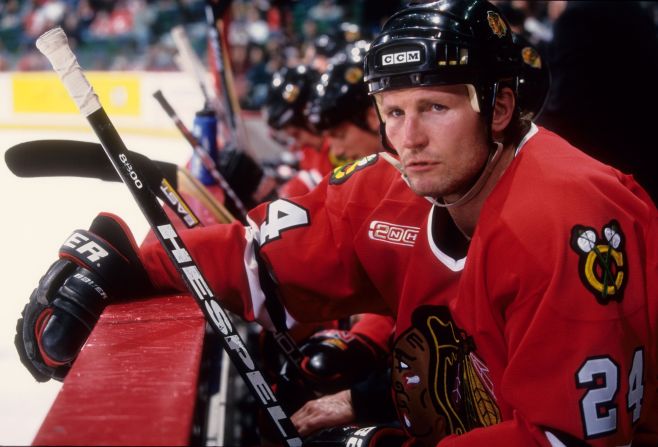

CTE is most commonly associated with football and boxing, but the disease has been found in the brain tissue of hockey players, wrestlers and, recently, in a Major League Baseball player.

With the most recent findings, it would seem that virtually no sport is immune.