Story highlights

Getting an honest picture of the unrest in Venezuela has its challenges

There are allegations of censorship, self-censorship and misinformation

There has been a media blackout in Venezuela, some say

Lots of information flows online, but lots of it has not been verified

The images coming from Venezuela over the past few weeks have been arresting: Troops shooting, protesters hurling rocks, people bleeding.

Just like the tear gas that clouds the scenes in photos, a complete picture of the truth in the confrontations is also hazy.

Allegations of censorship, self-censorship and photo manipulation have made it difficult for news consumers – especially Venezuelans – to form a complete picture of what is going on.

A media blackout has stymied the flow of information during some of the most intense days of clashes between anti-government protesters and authorities. In addition, strict regulations have pressured media outlets to tread softly when it comes to covering the violence.

There is more freedom on social media, but there are accusations that these channels of communication have been polluted by fake photos and misinformation. And the government allegedly blocked access to Twitter during protests last week.

“People don’t know what is happening and they depend on the dangerous or beneficial social networks because on social media, you can get truthful information. But also you can find people who misinform for their own ends,” said Carlos Acosta, a journalist for a Florida-based news startup that was created specifically to fill the gaps in coverage in Venezuela.

CNN iReport, the network’s user-generated platform, has received more than 2,700 submissions from Venezuela in the past week. Of those, more than 120 have been verified by producers and cleared for CNN.

These are developments that mostly have not been making it on to Venezuelan newscasts.

One vetted iReport video begins by showing a contrast: President Nicolas Maduro speaking on television about how things are under control, while outside a window, national guard troops are firing tear gas.

As he filmed, Giorgio Russo said the troops “aimed at me but since I live on the 14th floor I didn’t think they could reach, but I was wrong.”

A tear gas canister broke through a window and landed under a sofa, Russo said. His brother managed to throw the canister back out the window, but not before their 85-year-old father suffered from the gas.

In the western state of Tachira, in the city of San Cristobal, Alejandro Camacho captured video of student protesters “trying to be heard” by blocking streets and burning debris that cast an orange glow on them.

These reports provide under-reported vantage points, but what is the whole story? It is a challenge when unverified content is going viral and a government is blocking media.

Media blackouts

The ongoing protests grabbed the world’s attention on February 12, when two anti-government protesters and one government supporter were killed.

The day before, according to Human Rights Watch, the state broadcasting authority warned that coverage of the violence could violate a controversial law that prohibits the broadcasting of material that “foments anxiety” or “incites or promotes hatred and intolerance for … political reasons.”

As bullets flew and people died on the 12th, most outlets heeded the warning.

The Press and Society Institute monitored 38 radio stations the day of the killings and found that only five reported on developments in the day’s deadly violence and 30 transmitted “light programming. The other three echoed the government’s position.

The media silence “denied the citizenry the right to information of public interest and of relevancy for the safety of residents in the cities where the demonstrations unfolded,” the institute said in a report.

WATCH: Violence in Caracas on February 12

Comedian Luis Chataing, who also hosts a radio and television program, was among the majority who were silent on the airwaves on the violent day.

The next day, he apologized to his listeners and said he was ashamed of Venezuelan media.

Chataing told CNN en Español that he understands the restrictions the media is working under, but “this doesn’t help at all for the panorama to become clearer and for peace to be achieved as quickly as possible.”

How could it be, he asked, that while clashes were taking a turn toward violence, all one could find on television was a cooking show about how to fry eggs?

“I wanted to express myself as one more Venezuelan in my pain that the (national) media was not providing the coverage that I wanted about what is happening in Venezuela,” Chataing said. “Having to inform ourselves through foreign press is shameful.”

Photo manipulation

Social media is playing a vital role in the current unrest as an unfiltered channel for sharing images of protests and alleged abuses.

Government supporters are trying to cast doubt on the credibility of photos shared by the opposition by launching its own campaign to uncover what they say is manipulation of images.

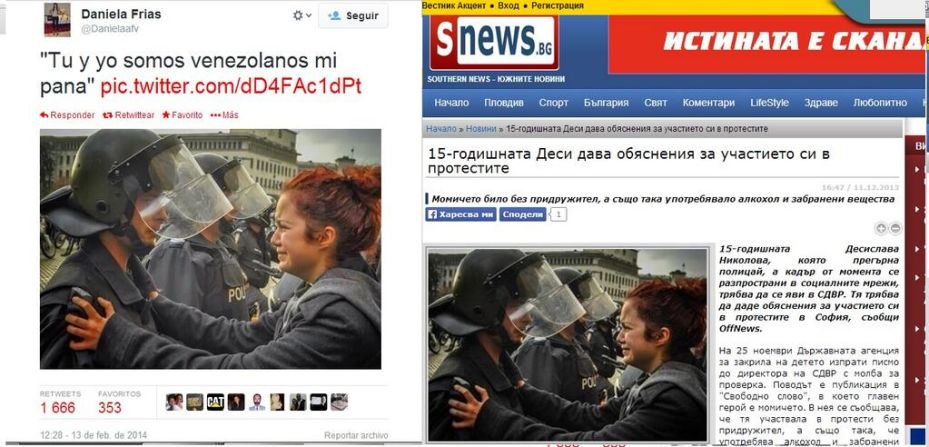

Websites and social media users who support the government are circulating a number of examples of images that the opposition claims to be from the Venezuela clashes, but are actually file photos from other events.

A photo of a student in a headlock by a soldier in Chile in 2011, for example, has been shared by opposition members to misrepresent the current violence in Venezuela, government supporters say.

Venezuelan actress Amanda Gutierrez apologized to her 228,000 Twitter followers after she shared a photo allegedly showing police forcing a protester to perform oral sex on them. The original image came from a U.S. porn site, a pro-government website said.

Another tweeter, to show the size of the support for the anti-government movement, shared a photo of a long human chain stretching out along a highway in Tachira state. But the photo appears to have been published originally last year in a Spanish newspaper and actually depicts protesters in Spain.

The examples of manipulated photos are but a drop in the fire hose of images being shared on social media, but sometimes that is all that’s needed to sow seeds of doubt.

The government’s position

Maduro’s government makes its own claims – that the protesters are in cahoots with the United States, that there is coup in the works, that the opposition is behind the deaths – but rarely offers evidence or elaborates.

The accusations find space on state-owned media, and the government complains that other outlets are biased against it.

In an interview with CNN en Español, Venezuela’s ambassador to the Organization of American States, Roy Chaderton, accused international media, including CNN, of bias in its coverage.

Reflecting on the protests, he said, “We are expecting the democratic evolution of these events, of which there has been very little coverage of the government position.”

The government had already initiated a dialogue with the opposition, including meetings with opposition mayors and governors.

“But that’s not news,” Chaderton said. “What’s news is a car lit on fire, or a death blamed on the government or the opposition in these clashes.”

The cameras are focusing on police on the streets, and not on the protesters who throw rocks or Molotov cocktails, he said.

Twitter troubles

It’s not been just the content, but access to social media that has been a roadblock to gathering information.

Those who have taken to social media accused the government of blocking access to Twitter last week.

Hundreds of Twitter users in Venezuela reported difficulties using the service, and a Twitter representative confirmed that images posted on Twitter were being blocked in the country.

The Venezuelan broadcasting regulator denied that the government interfered.

Venezuela’s minister of communications, Delcy Rodriguez, also used Twitter – to bash Twitter users.

“Social media is being used by violent coup plotters to create anxiety in the public in a psychological operation of great scale,” she said. “Powerful media laboratories are being employed to advance a psychological war without precedent against Venezuela.”

Telling fact from fiction

Telling the whole story in Venezuela is not a new challenge.

The government’s clampdown on private media has left little room for views outside of the official line.

Venezuelan journalists in Florida created a new channel that streams online called ElVenezolanoTV. It was slated to go live next week, but the protests caused it to move up its debut.

Many of the journalists on board are considered “opposition journalists” by the Venezuelan government, but they say their goal is to present unbiased journalism. The government has an invitation to come on their air anytime, its journalists say.

CNN also goes through great lengths to verify the iReports that are submitted.

Producers speak to the person who uploaded the iReport, check metadata and cross-verify whether the image is original, fact check any allegations, and add additional context and reporting as needed.

In one extreme case, a violent video that depicts protesters and officials clashing took more than 10 hours to fact check and approve. The effort was worth it, said Juan Muñoz, director of social media for CNN en Español. “It´s an amazing iReport. The best one I have ever seen on the platform.”

CNN’s Fernando del Rincon, Carlos Montero, Adriana Hauser, Gabriela Matute and Katie Hawkins-Gaar contributed to this report.