Editor’s Note: Heidi Beemer, a first lieutenant in the United States Army, is a chemical defense officer in the 63rd Chemical Company at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

Story highlights

Mars One, a nonprofit, aims to establish the first human settlement on the Red Planet

Heidi Beemer: I signed up to volunteer for a one-way trip to Mars

She says despite risks and challenges, the trip is worthwhile in what we can learn

Beemer: For one thing, the human race can fulfill its dream of living on another planet

I signed up to volunteer for a one-way trip to Mars. Yep, one-way.

Mars One, a Dutch nonprofit organization, aims to establish the first human settlement on Mars in the coming decades. I am one of 1,058 people chosen from around the world to be in round two of Mars One’s astronaut application pool. The next few rounds will narrow the field until at last 24 candidates will be picked to begin 10 years of training for the mission.

The process is very competitive. In my application, I highlighted my strengths, including adaptability, resiliency, curiosity and leadership skills. I am ready to accept all the hard challenges of going to space and living on Mars.

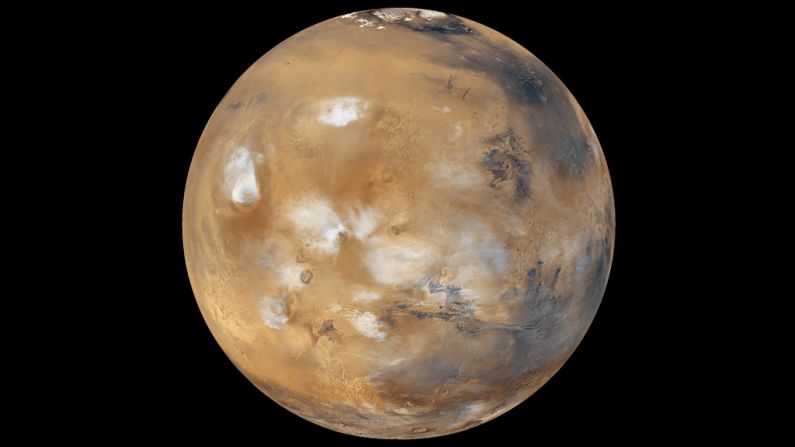

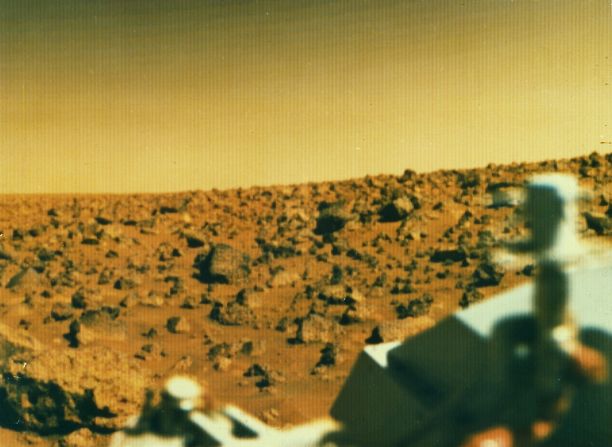

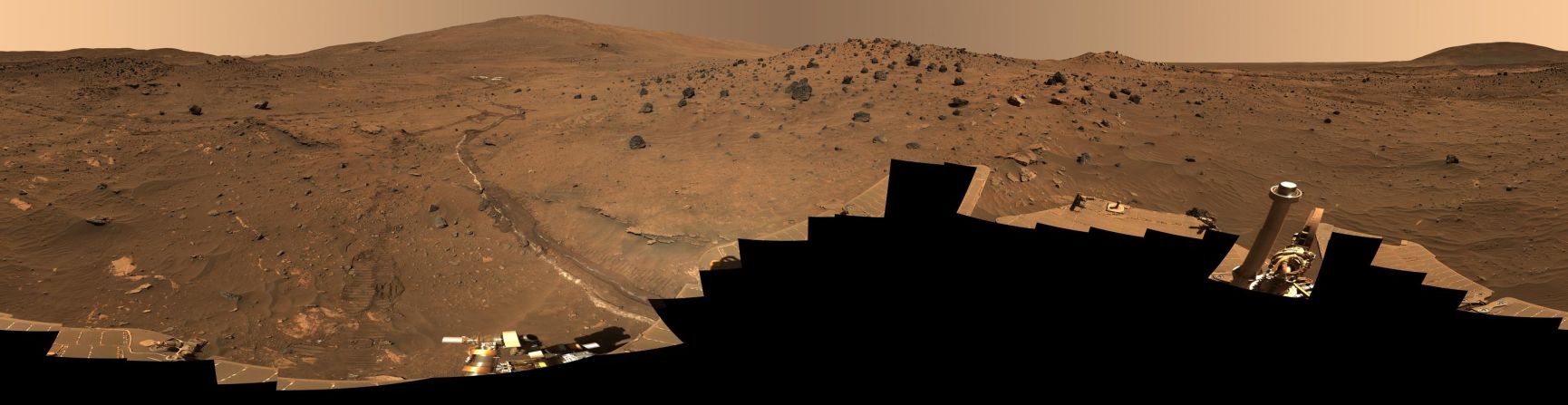

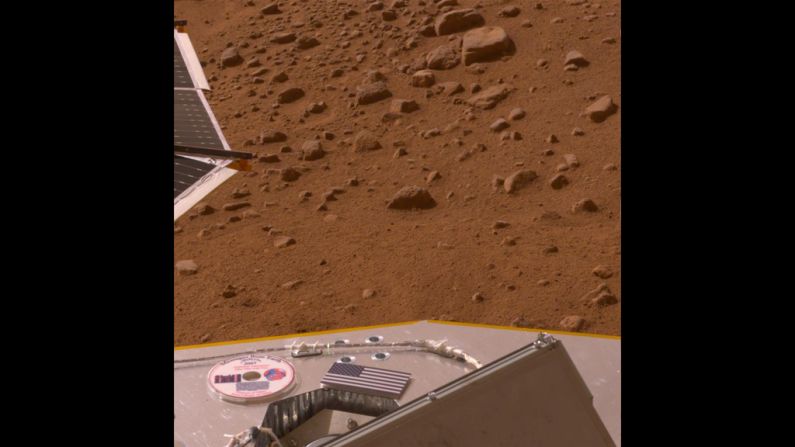

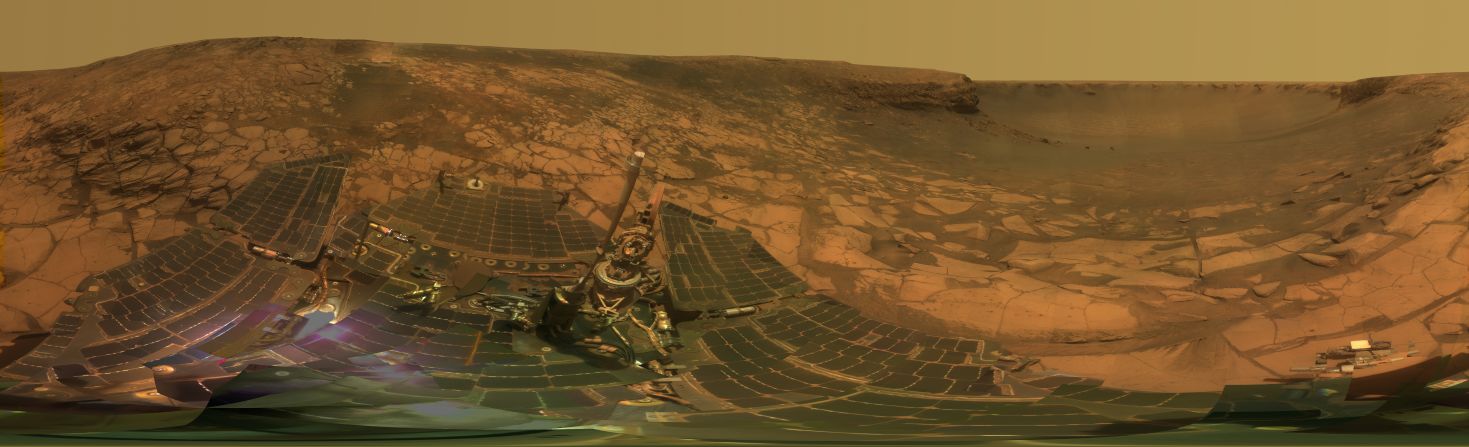

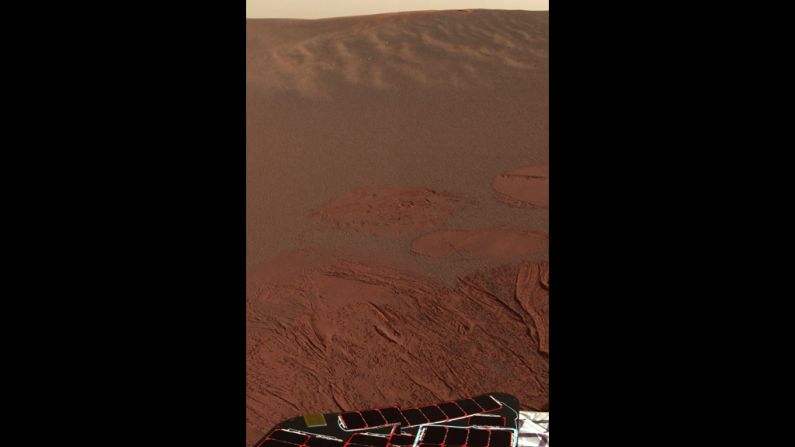

My passion for Mars and space exploration began in 1997 when I was 8 years old. NASA had been sending humans to space for several decades, but it began to push new frontiers by sending the first rover to Mars. The Sojourner rover landed on the Red Planet on July 4, 1997, and gave humans a glimpse of the rust-colored Martian surface.

Seeing the images ignited a passion inside. For most people, perhaps the desolate landscape of Mars is uninviting; for me, it was the future – the next frontier. I remember telling myself then that the only way we will find the answers locked inside our solar system would be to send humans to Mars; and I wanted to go.

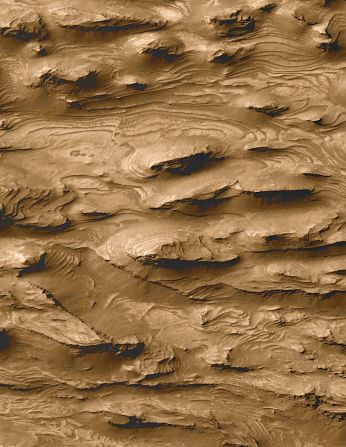

When I was a senior in college, I was selected to be the executive officer and chief geologist of Crew 99 at the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah. Much like the astronauts on the International Space Station learn to live and work in space, the Mars Society’s MDRS outpost teaches us how to live, work and solve problems on Mars. My crew consisted of five other students from across the country and we lived at a Martian analogue station for two weeks. We learned how to conduct daily missions, maintain our habitat, take quick showers and utilize recycled water systems.

Although our two-week stay is relatively short compared to Mars One’s lifelong expedition, it is scientific research like this that is going to help us find a way to adapt to living on other planets.

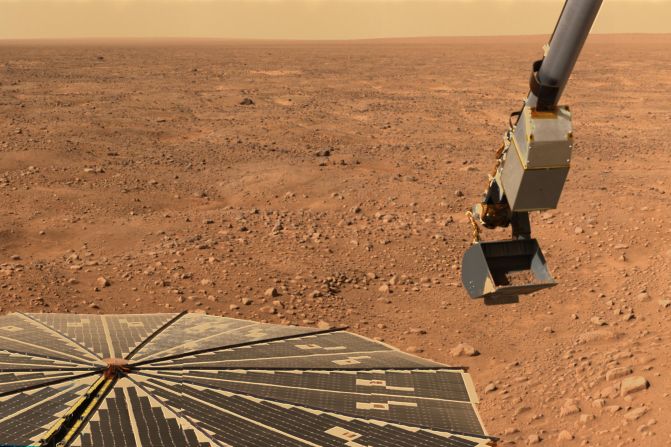

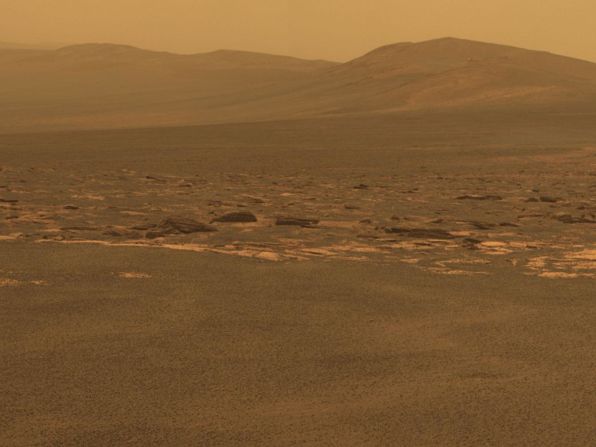

Once the Mars One crew arrives on Mars the members will begin living their lives as Martians. A majority of their time will be spent conducting scientific experiments, exploring the surroundings, maintaining and improving their habitat. They will also stay connected with the world they left through e-mail and video messages. They will live like the scientists at MDRS and spend their days learning how to adapt to a foreign environment.

The opportunity the Mars One project presents is extraordinary. Humans have always dreamed of living on another planet. The technology to send us to the surface of a planet like Mars exists; it has been available for more than 20 years. But limited funding and unknown health risks have put a brake on our desire to try to settle on other planets.

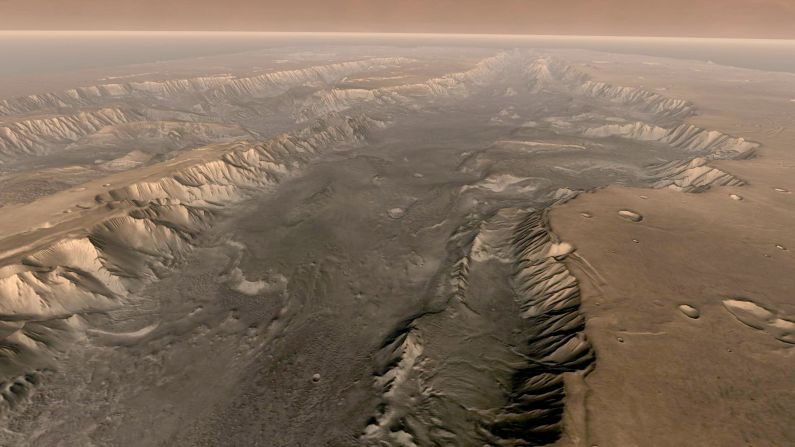

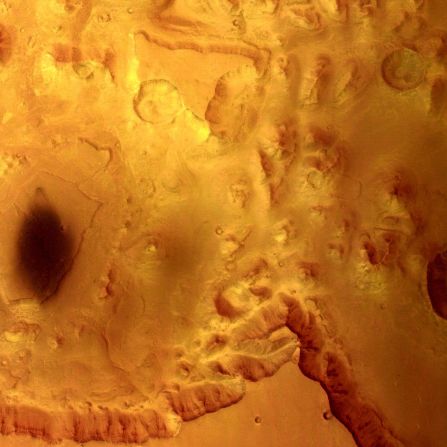

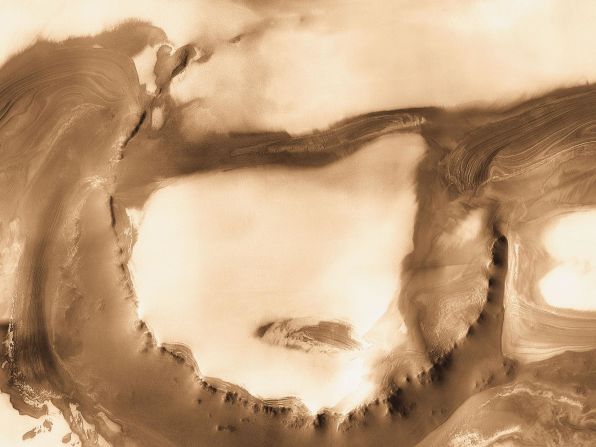

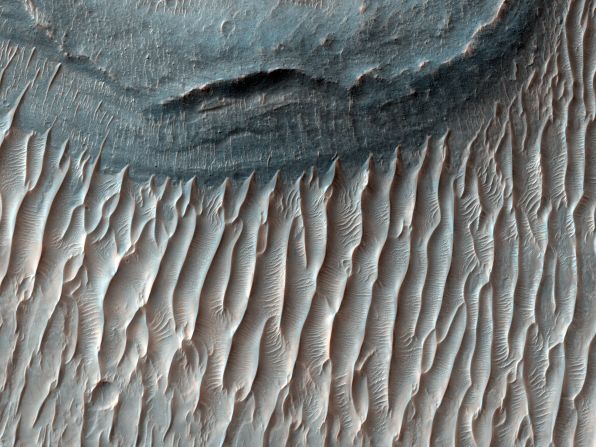

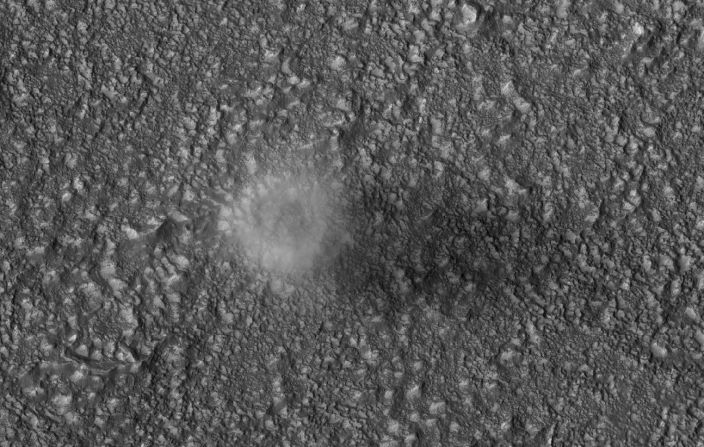

Because Mars mysteriously lost its atmosphere and oceans millions of years ago it is important for us to find out why. By sending humans there, we can find answers to Mars’ past and future, and ultimately, maybe find answers to the future of Earth.

Of course, there are concerns about whether it makes sense to start a human settlement on such a cold and harsh planet. In an article in The Times, astronauts and physicians acknowledge that the human body isn’t equipped for long-term space travel. Risks include extended exposure to radiation and cosmic rays. Even at low and acceptable levels, they may cause health problems.

Luckily, it does not take a lifetime to travel to Mars. In fact, it may only take 210 days to reach the Red Planet. This is a mere 30 days longer than a normal crew rotation on the International Space Station.

While we know about the negative toll of prolonged space living on the human body, astronauts returning to the gravitational force of the Earth recover from their stay in space. Although research is still being done on the loss of bone mass, most other effects felt during space missions subside after physical therapy and treatment.

Mars is also a much smaller planet than Earth. This means the gravity felt on the surface is one-third what we feel on Earth. Once the settlers arrive on the surface after a seven-month space journey, their bodies will eventually adapt to the surface of Mars.

Obviously, there will be unforeseen challenges in such a huge endeavor. But they shouldn’t deter us from the attempt. If we never put our collective efforts together to do this, the human race will never fulfill its dream of living on another planet. We owe it to future generations, who will be left with the problems of Earth, to try to find new homes throughout the solar system. As long as there are volunteers like me willing to make the sacrifice, we will find ways to survive in space and beyond.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Heidi Beemer.