Story highlights

Nationwide network helps sex assault survivors file federal complaints against schools

Survivors say schools are violating federal civil rights laws by creating hostile environment

Schools accused of mistreating students, failing to conduct inquiries in timely manner

"There's not a single school that isn't thinking about this," professor says

For a long time, Joanna Espinosa struggled to make sense of it all.

Yes, he was her boyfriend. No, he hadn’t pinned her down, or threatened violence. But Espinosa insists that he coerced her, psychologically and physically, into having sex against her will for most of their three-year relationship. She resisted, told him no, pushed him away. More often than not, he persisted and she gave in “just to get it over with,” she says.

“I knew that it was sexual assault, but at the time, I felt extreme shame and was not ready nor willing to fully accept what was happening,” said Espinosa, 24. “Like most unpleasant truths, I buried it until the end of my relationship, when I realized I was holding onto a relationship with a man who was abusive.”

The relationship came to an end in February 2013. The next month, Espinosa filed a sexual harassment claim against her former boyfriend with her school, the University of Texas-Pan American, where some of the incidents occurred. The reporting process was traumatizing in its own right, she says, leading her to file a federal complaint against UTPA. The Title IX complaint, filed last week with the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights, alleges that UTPA violated her right to an education free of gender-based discrimination by mishandling her report and creating a hostile environment.

Campus sexual violence complaints

A university spokeswoman said the school had not seen Espinosa’s complaint, but noted the school does not comment on pending investigations. However, the school stands by the findings of its investigation into Espinosa’s report, the spokeswoman said in an email.

Espinosa’s complaint makes the UTPA the latest school to face criticism for its handling of a sexual misconduct report. So far in fiscal year 2014, the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights says it has received 16 complaints that included Title IX allegations specifically related to sexual violence. Those numbers come on the heels of a marked year-to-year increase in complaints the department received, from 17 in 2012 to 30 in 2013.

Espinosa says she would not have come forward without the help of a nationwide network that has been a driving force in bringing attention to the way schools handle sexual misconduct reports. President Barack Obama recently called the nationwide, student-led movement a catalyst for a federal task force to protect college students from sexual violence on campus.

Rape is a longstanding issue on college campuses, but the latest movement, led by student activists, survivors and faculty, recasts sexual violence as a cultural problem on campuses nationwide – not just a series of isolated incidents. Students are taking matters into their own hands, filing complaints en masse and speaking out publicly.

They’ve flocked to advocacy groups such as End Rape on Campus and Know Your IX, which sprang from grassroots activism around university handling – or mishandling – of sexual violence.

Espinosa says she went to the school first because she thought that without concrete evidence, law enforcement would not take her seriously – a common experience among people who report rape to law enforcement, experts say. Besides, she knew that colleges and universities are federally mandated to investigate sexual violence under Title IX, which guarantees students the right to an education free of sexual violence, which is considered a form of discrimination.

Stay in touch!

And, when she went to the city of Edinburg Police Department after filing her report with the school, she says they told her that her case would be difficult to prove and took her phone number. She never heard back from them, she says.

Her experience with university administrators was no better, she says. They questioned why she didn’t come forward with the abuse claims sooner, suggesting she was acting out as a spiteful ex-girlfriend. In one meeting, she says, administrators asked whether their relationship was “Facebook official” or whether there was a “promise of marriage.”

It took five months for school administrators to reach the conclusion that Espinosa’s complaint was “unsubstantiated.” They did, however, conclude her ex-boyfriend abused his access to university facilities, and placed him on disciplinary probation for the remainder of his academic career, according to documents provided by Espinosa.

Espinosa’s voice quivers as she recalls the ordeal, which led her in 2013 to drop one class in the first summer session and request an incomplete in the second. It was a punch in the gut after sleepless nights and constant self-doubt, she said. She appealed the decision, but the administration upheld it. She reached out to advocacy group End Rape on Campus, and a member of the group helped her file a complaint with the federal Office of Civil Rights.

“I’m not sure I would’ve come forward if all these people hadn’t done it before me,” Espinosa said. “I needed the validation. I needed someone to confirm, ‘You’re right you’re not blowing things out of proportion.

“It was a relief to hear someone tell me, ‘You have a case, and they shouldn’t treat you this way.’”

The U.S. Department of Education laid out minimal requirements in a 2011 “Dear Colleague” letter for schools to follow in responding to reports of sexual harassment, or risk loss of federal funding.

The 19-page letter reminded schools that under Title IX, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex, colleges and universities must apply a “preponderance of evidence” standard to reviewing rape cases, which means they must operate under the assumption that “more likely than not that sexual violence occurred.”

Now, many are under scrutiny from the federal government. The U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights has 35 pending Title IX investigations involving allegations of sexual violence at schools such as the University of North Carolina, Princeton, Harvard, Swarthmore, the University of Southern California, Dartmouth and Occidental, a Department of Education spokesman told CNN.

The bravery of students who’ve spoken out – and their ability to connect to each other through social media – has sparked a paradigm shift on campuses, said Gina Smith, an attorney who has consulted with schools around the country on sexual assault policy.

“What we’re seeing is a demand that schools treat complainants with compassion,” Smith said. “Schools are stepping up and taking notice.”

From one campus to the next, the concerns are mostly the same, said sexual assault policy consultant Leslie Gomez: lack of clarity, students being mistreated, complex procedures and insufficient training among those leading the processes.

Here are just some of the students and activists trying to change the way their schools handle sexual violence – for good. CNN does not name survivors of sexual assault, but is doing so in this case because these people, including Espinosa, chose to come forward in the hopes of holding their schools accountable and encouraging others to speak up.

Sarah O’Brien, Vanderbilt University

Despite an ongoing, high-profile rape case involving four football players, Nashville’s Vanderbilt University community hasn’t exactly rallied to change campus culture, alumna Sarah O’Brien, 22, said. But that hasn’t stopped O’Brien and others from working with administrators to clarify the school’s policies around sexual violence, and raise awareness of how the school can help.

“Our campus is not liberal and it’s not activist, so when a group of students come together around an issue it stands out,” says O’Brien, who graduated from Vanderbilt in December.

In 2010, an acquaintance raped her while she was drunk, she said. A series of frustrating encounters with school administrators led O’Brien to come out publicly as a rape survivor in fall 2012.

One administrator attributed her PTSD to the stress of being a student athlete; another told her a statute of limitations prevented her from reporting the rape.

She later found that Title IX gave her the option of seeking academic leniencies due to her PTSD diagnosis, but such provisions were not laid out Vanderbilt’s policy, she said.

“I just felt that university failed me in a lot of ways,” O’Brien said. “As I started talking to other women [at Vanderbilt], it became a common complaint.”

After going public, she organized a Take Back the Night event and began working with student athletes and survivors. She reached out to Know Your IX’s founders, culminating in a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education accusing Vanderbilt of violating of Title IX and the Clery Act, a federal law that requires public disclosure of crimes on campus.

The same month, campus group Vanderbilt Students of Nonviolence delivered an 11-page list of demands. Students asked the school for a single office focused on sexual assault prevention and treatment; a website that pulls together all campus resources and protections afforded under Title IX; posters around campus discouraging sexual violence; inclusion of students on boards related to campus life and sexual assault policies; and more training in sexual assault prevention for people on those committees.

It’s what O’Brien looked for and couldn’t find after her alleged assault, she said.

“The last thing you want to is dig through a bunch of websites and contact administrators who don’t know even know the policy when you’re dealing with a sexual assault,” she said.

Already, changes are under way. The campus hosted an open forum on sexual violence led by a lawyer.

In an e-mailed statement, Beth Fortune, Vanderbilt’s vice chancellor for public affairs, said posters are up that say, “Sex without consent is sexual assault.” The Project Safe website is live and the office is underway, among other efforts.

“We want to make it as easy as possible for victims of sexual misconduct to get the services they need,” Fortune said.

Since graduating, O’Brien is still involved with Vanderbilt Students of Nonviolence. She’s also working to build a shelter for survivors of sexual violence in Nashville.

“I think change will be a slow process,” she said, “but we’re starting to see it.”

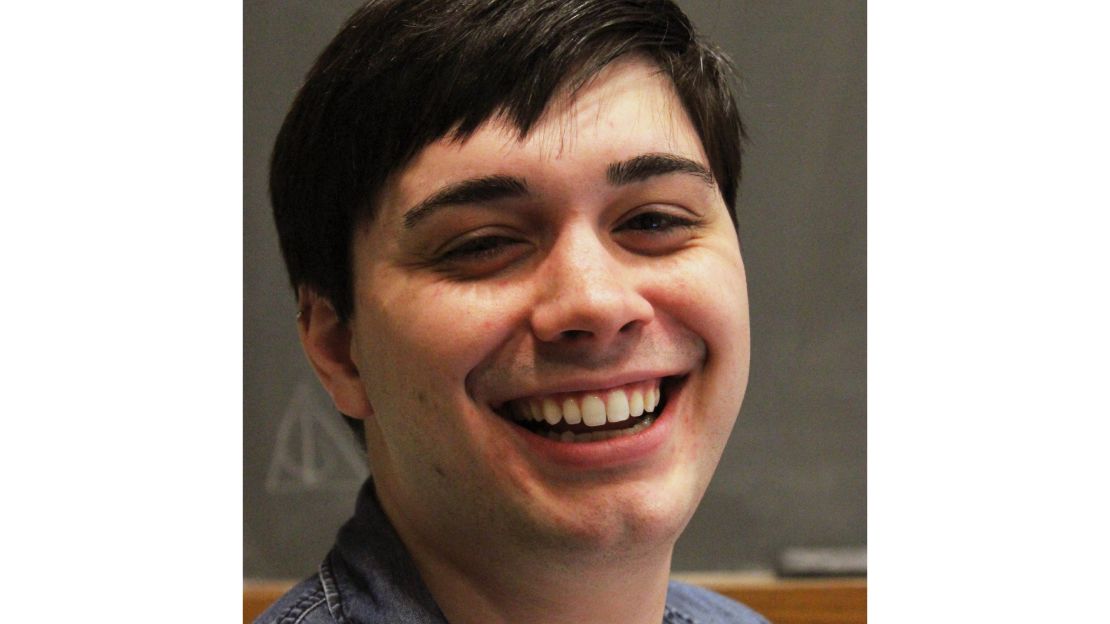

John Kelly, Tufts University

Rape is something anyone can experience, regardless of gender or sexual orientation. It’s something John Kelly knows firsthand, and wants others to remember.

In just 18 months, the 20-year-old Tufts University student has gone from admitting to himself he had experienced partner rape to becoming a leading LGBTQ voice on education policy about sexual assault.

Like many survivors who go public, he did so out of frustration with his school’s adjudication process. Kelly believes the Massachusetts university let his attacker off easy – he was suspended, rather than expelled – because the school didn’t consider oral sex to be rape.

“It was really traumatic, trying and poorly executed,” Kelly said of Tufts’ adjudication process.

But other parts of the process revealed where Tufts “did a fantastic job.” The Title IX office performed a thorough investigation and advocated on his behalf when he was hospitalized after a suicide attempt, Kelly said. It facilitated a no-contact order for his attacker, arranged therapy and made sure he could return to classes.

“I saw the potential for Tufts to have a really strong policy,” he said. “We were halfway there; the problem was in the punishment phase.”

Kelly ran for student senate and got involved with the campus group Action for Sexual Assault Prevention. It teamed up with another group, Consent Culture Network, on an April 2013 letter to Tufts officials, calling for eight major policy changes.

A Tufts University spokeswoman said the school began to “take a deep look at all of its policies and procedures regarding sexual misconduct,” after the 2011 U.S. Department of Education letter, and continued those efforts in 2013, when the university president convened the Task Force on Sexual Misconduct Prevention.

School officials would not comment on Kelly’s case, and he has not filed a Title IX complaint against the school. He says he is trying to make headway by working on a task force subcommittee addressing prevention through policy and campus culture.

He’s also working with the national organization Ed Act Now, which drew more than 175,000 signatures on a petition urging Education Secretary Arne Duncan to hold schools accountable for failing to comply with Title IX and Clery laws.

Kelly and others met with Duncan and others from the Obama administration and Department of Justice. He now serves on the Department of Education’s Negotiated Rulemaking Committee on the Violence Against Women Act, helping to shape the regulations surrounding recent changes to the law.

“We want to make things more survivor-centered, make sure support systems are in place to increase students’ mental, emotional and physical safety,” he said.

Sofie Karasek, University of California,Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley was Sofie Karasek’s dream school, a progressive campus, perfect for an activist like herself. She never imagined she’d be advocating for herself.

Karasek said her path took a detour one night in her first year, when she was sexually assaulted at an off-campus event. Ashamed, she told just a few others, and buried the incident – until she learned the same person had assaulted three other students. In April 2012, they met with administrators to tell their story. The following month, Karasek and two others filed a report against him with the school, and waited to hear back.

Six months later, Karasek said she heard through a mutual friend about the resolution: He would be graduating early. No investigation had been conducted as far as she knew; at least none involving her or the other women.

“I gave them the benefit of doubt,” she said. It turned out they weren’t talking to anyone except him, she said, “to resolve it on his terms.”

The school responded to Karasek’s request for an update two days before his December 2012 graduation, saying that he had been found in violation of the student code of conduct and that the case was solved through an early resolution process, she said. The school only confirmed in September 2013 that he had graduated in December, she said.

UC Berkeley did not respond to requests for comment.

Karasek was emboldened to speak out about her experience. With the help of students from other universities, she and eight other students filed a Clery complaint against UC Berkeley in May. But instead of filing the complaint silently, she and another student issued a press release while attorney Gloria Allred held a press conference to announce that complaints had been filed against Berkeley, Dartmouth, Swarthmore and the University of Southern California.

The experience has launched Karasek into the activist spotlight. She testified at a joint legislative committee hearing in August 2013, leading the state legislature to order an audit of sexual assault policies at UC Berkeley and three other state schools. The results are expected in April.

In December, an aide from California Assemblyman Mike Gatto’s office reached out, asking whether she would testify on behalf of a bill requiring universities to report all sexual assaults and violent crimes to local law enforcement. Karasek suggested modifying the bill to require that that all violent crimes be reported except in cases where survivors request otherwise. He listened and introduced the amended bill to the state education code with her suggested caveat.

But progress at UC Berkeley has been “lackluster,” Karasek said. In September, the school introduced an interim policy that allows survivors to appeal their cases, among other changes. But Karasek wishes more meaningful improvements would come, including more staff dedicated to the issue, as well as Title IX coordinators, and for the “preponderance of evidence” standard written into UC Berkeley’s policy.

Really, what Karasek wants is the school to implement a process for formal hearings and investigations in sexual assault reports – something that was missing from her experience with the reporting process, she said.

But a Title IX advisory committee convened by the school chancellor to review policies that she sits on has only met once, she said. Otherwise, nothing much changed, she said.

“The people who are dedicated to changing policy are students,” she said. “We’re recognizing the snowball effect that comes from speaking out.”

Caroline Heldman, Occidental College

Caroline Heldman remembers how it feels to go to bed hungry or cold. She grew up poor in rural Washington state, and remembers the “pain of people looking down on you,” of being the first person accused when something went missing, and being shunned and teased. Still, her father’s Pentecostal leanings ingrained in her a duty to serve others and the view that “someone else’s suffering is my own suffering,” she said.

Heldman, an Occidental College professor, has become one of the leading faculty figures helping students file federal complaints involving the handling of sexual assault cases.

“There’s not a single school that isn’t thinking about this,” Heldman said.

Heldman and colleague Danielle Dirks helped 37 students and alumna file a Title IX complaint in 2013. She served as a faculty advisor to End Rape on Campus, which connects survivors with resources for treatment and options for holding schools accountable.

This past week, in a Google Hangout, she walked Espinosa, the University of Texas-Pan American student, through the process to file her complaint.

“My work is very much driven by the fact that we don’t live in a meritorious society and some people are more likely to experience pain and suffering than others,” she said. “A lot of us are very comfortable acknowledging that given certain circumstances, we could be in the same bad situation as someone else. But it’s more than that – it’s about seeing yourself in others.”

As a young idealist, Heldman thought she could fix everything that was wrong in the world – from the headlight ordinances she argued for as a child in Washington to the social justice causes she took up as an undergrad.

As a full-time professor with tenure at Occidental, Heldman feels a responsibility to speak up about how schools treat victims of sexual violence. Many educators have less freedom to speak out about controversial topics, she said, which puts her in a unique position to help.

“Power in colleges has shifted dramatically in recent years to the administrative side,” she said.

“Those of us who are tenured need to use our academic freedom because we’re the only ones at institutions who have power to speak out when administrations mistreat students.”

Anusha Ravi, Emory University

As far as Anusha Ravi is concerned, how a school deals with sexual assault is a reflection of the entire campus community – and it’s everyone’s job.

As more schools made national headlines with students’ allegations of mishandling of sexual assault reports, Ravi began to wonder, how are handling these kinds of things at handled at her school, Emory University in Atlanta?

That’s why the 20-year-old political science student joined the student group Sexual Assault Peer Advocates. The group provides training to undergraduate and graduate students about how to talk to sexual assault survivors.

It’s a skill most college students will need at some point, Ravi said. She has not personally experienced sexual assault, but she knows people who have. Understanding how to talk about sexual assault fosters a climate of openness within the school community, she said.

Because sexual assault affects women more often than men, she said, a school’s mishandling of sexual assaults projects a sexist image, and for better or worse, so much has to do with image.

“It doesn’t look good for higher education in general and doesn’t make an institution look good,” she said. “As a college student, I do believe that when people are evaluating their own education, they’re not only looking at classes, but campus culture and safety.”

So far, Ravi is satisfied with Emory’s approach.

After the 2011 Department of Education letter, Emory created a university-wide sexual misconduct policy and adjudication process in 2013, a university spokeswoman said in an e-mail.

The school now has Title IX coordinators for each college and supports groups such as Sexual Assault Peer Advocates in its efforts to improve campus culture.

The group has trained more than 1,000 people, from fraternity groups to residence advisers, Ravi said.

“Nobody wants to be the school that treats people poorly, especially sexual assault survivors,” she said. “We all have a role to play.”

Teens trained to spot drama before it turns dangerous

CNN’s Jamie Gumbrecht and Toby Lyles contributed to this report.