Story highlights

Dr. Lynn Webster is being investigated by the Drug Enforcement Administration

Webster ran the now-shuttered Lifetree Pain Clinic in Salt Lake City

There was "zero oversight," says one man whose wife died of an overdose

Painkiller-related overdose deaths are skyrocketing nationwide

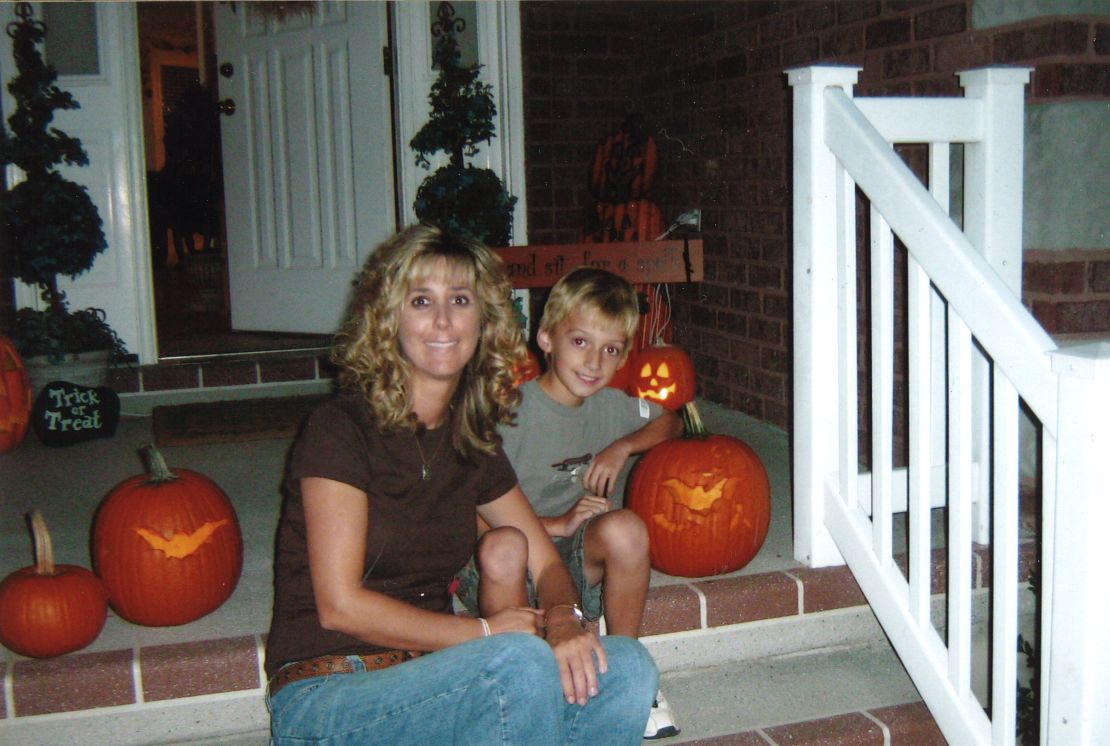

In one photograph, Carol Ann Bosley is bent precariously at the edge of the couch, asleep, her mouth still filled with food.

In another she is unconscious, her body draped over a clothes basket, clutching a tennis shoe in one hand.

For years, Roy Bosley took these and other chilling photographs of his wife to prove to her – and her pain doctor – that she was repeatedly overdosing on prescription painkillers.

“She’d take the pain medicine and about an hour later she would be confused, think she hadn’t taken it, and take it again,” said Roy Bosley, explaining how his wife’s frequent overdoses began.

“We would find her unconscious various places in the house and find things like ice cream in a cupboard. The house would be a disaster, and she’d be asleep in the den.”

The episodes, said Bosley, were not simple confusion about dosing.

Years after a car accident vaulted her through her car’s windshield, and after multiple spine surgeries, in 2008 Carol Ann Bosley became a patient at the Lifetree Pain Clinic in Salt Lake City.

It was there, her husband said, that she got a steady and increasing supply of prescription painkillers. Soon after her first office visit, Bosley said “…she was hooked on the pain medicine, she needed it.”

According to an analysis of her medical records – by a physician retained by the Bosleys’ attorney – about a year before her death, Carol Ann Bosley was taking a painkiller and an anti-anxiety medication, amounting to around 100-120 pills per month.

By the time of her death, she was prescribed seven drugs, totaling about 600 pills per month.

‘Seriously flawed’

According to the same physician, this pattern was seen with other patients who received care at Lifetree.

A separate medical malpractice claim, filed against Lifetree staff on behalf of a 42-year-old woman who died after receiving care at the clinic, describes her treatment for chronic back pain and headaches.

According to the claim, in 2001 the patient was taking “…about 200 prescription medication pills per month, equating to about 6.5 pills per day.”

Seven years later, “…at the time of her death she had been prescribed 1,158 pills per month, equating to about 41.4 pills per day.”

What makes the allegations against Lifetree so stunning: Before it was sold in 2010, the clinic was run for more than a decade by Dr. Lynn Webster, an anesthesiologist and pain medicine specialist who is considered a leading expert on how to safely prescribe opioids – drugs that act on the brain to dull a person’s perception of pain.

Webster is president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine and developed the “Opioid Risk Tool,” a checklist to help doctors siphon out legitimate opioid users from potential abusers.

“Dr. Webster teaches a system that supposedly makes this treatment safe and effective,” said Dr. Andrew Kolodny, president of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing. “But when you think about the fact that he’s had multiple deaths in his clinic from overdose, it suggests that the system he is teaching is seriously flawed.”

Webster, and the deaths at his now-shuttered clinic, are the subject of an ongoing investigation by the federal Drug Enforcement Administration.

CNN reached out to Webster for a response to allegations raised by former patients’ family members and, through a spokesman, he declined.

According to that spokesman, who did not want to be named, Webster considers it, “…morally and ethically indefensible to comment openly on the intimate details of treatment of patients at his clinic.”

But Webster did provide a statement: “It is a tragedy of the worst kind when a patient suffers from abject pain and dies, not from a result of treatment, but in spite of it.

“Those of us at Lifetree Pain Clinic who treated patients with chronic pain know this firsthand; we grieve for the patients who passed as well as their families.”

Deaths among Lifetree patients, allegedly because of overprescribing, occurred against a national backdrop of skyrocketing painkiller-related overdoses.

About three people die every hour in the United States after overdosing on prescription drugs, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; most of those deaths involve prescription opioids. Utah has one of the highest drug overdose rates in the country.

What complicates the picture is an essential quandary when it comes to prescribing painkillers: They are useful when used short-term and for extreme pain, but there is no evidence that long-term use is either safe or effective.

In fact, the longer a patient takes high doses of prescription opioids, the more likely they are to become addicted and eventually overdose. Many pain management experts say overprescribing is at the heart of the overdose problem.

A recent Johns Hopkins study showed that between 2000-2010, opioid prescriptions given after pain-related doctor visits nearly doubled – from 11% to 20% – while identification and treatment of pain stayed the same.

“If you listen to what some of the leading pain specialists are saying today about opioids, they’re saying these past 15-20 years have been a disaster,” said Kolodny, a psychiatrist and chief medical officer at the Phoenix House, a nonprofit addiction treatment organization.

“We’re harming far more of our patients than we’re helping when we prescribe opioids aggressively.”

‘Zero oversight’

Aggressive prescribing practices, according to lawsuits, were common at Lifetree.

What fuels fury, and wonder, among some family members of patients who died is that the deaths are associated with a clinic run by a doctor so highly regarded in pain management circles.

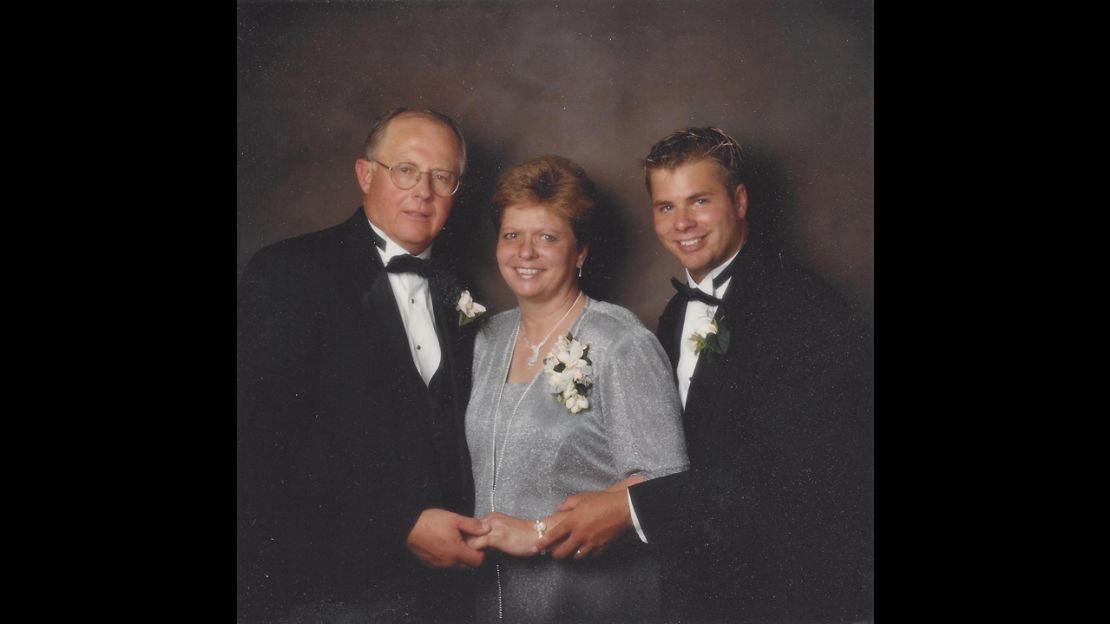

“He doesn’t even follow his own advice,” said Bruce Webb, whose wife, Tina, died at age 39, less than two years after beginning treatment at Lifetree. “It would be really interesting to find out how many patients (at Lifetree) really died from overmedications, from overdoses.”

Webb said his wife complained about migraines and jaw pain, and for years found relief with 30-pill-per-month prescriptions of Tylenol 3 and 4, painkillers containing acetaminophen and codeine.

“One day she took a little bit too much medication and felt good,” said Webb. “So then she did it again, and did it again, and did it again, and then pretty soon the 30 pills wasn’t working.”

Tina Webb was accused of doctor shopping – going from doctor to doctor to get multiple pain prescriptions filled – and in 2005 was referred to Lifetree for monitoring.

When she began treatment there, it was under an agreement with the district attorney. According to a document related to her case, she “…recognizes that she has not managed her pain appropriately,” and needed monitoring by a pain management clinic.

But monitoring is not what Tina Webb got at Lifetree, said Webb. She was first seen by Webster, then on subsequent visits had her care handled by a nurse practitioner.

“I was assuming that Dr. Webster was reviewing charts of (the nurse practitioners’) patients, looking at how much was being prescribed and that there was some oversight,” said Webb. “There was zero oversight.”

Fourteen months after her first appointment at Lifetree, Webb was being prescribed a powerful cocktail of short and long-acting painkillers, sedatives and sleeping pills. According to an analysis of her medical records, by a physician retained by Webb’s attorney, her dosages had increased by 600% since her first visit.

Around the same time, Bruce Webb noticed she began acting erratically and irresponsibly at home. She crashed the family car into the garage, and often would nod off at dinner while food slid off her fork.

She also became frequently, and easily, confused.

“One night she came to me, woke me up in the middle of the night and she said, ‘I can’t find my room, can you help me find my bed?’” said Webb. “So I had to get up, walk around, and help her get in bed. She didn’t know where she was.

“The next morning I asked her, ‘What was that all about?’ She goes, ‘What?’ She had no idea, no recollection, of what had happened that night.”

As his concerns grew, Webb decided to track his wife’s medication. Every night after she fell asleep, he would get up and count her pills. Over the course of months he found that she was taking double – sometimes triple – the suggested dose.

“She was supposed to be taking six (pills) and would be taking 16,” said Webb. “A whole cocktail of them, and they were all short (of the number they should have been).”

According to Tina Webb’s medical records, on several occasions she went to Lifetree – days or weeks before scheduled appointments – to ask for an early refill. Those requests were almost always granted.

“There were obvious signs of dependence, abuse, and (a nurse practitioner at Lifetree) kept filling the prescriptions,” said Webb.

‘I just sobbed like a baby’

Webb said he tried contacting staff at Lifetree repeatedly to vent his concerns about his wife, and they claimed that patient privacy laws prevented them from discussing her case.

Roy Bosley said he got the same response when he tried to contact Lifetree staff, including Webster, about Carol Ann Bosley’s behavior.

“When I called I said, ‘I am not asking for information,” said Bosley. “‘I am asking to communicate critical information with regard to the well-being of my wife.’ And I was given the (privacy) excuse and that was the end of it.”

As the photos of Carol Ann Bosley unconscious began to stack up, so did the hospital visits after overdoses. Eventually, she was persuaded by her family and emergency room doctors to enter treatment for her addiction to painkillers.

Soon afterward, Bosley said, his wife lost weight and shed her dependence on prescription opioids, managing her pain on Tylenol only.

But just as she was adjusting to a life free of painkillers, Bosley said she got a phone call from Lifetree, requesting that the Bosleys both meet with Webster. During that meeting, Roy Bosley said Webster convinced his wife to resume taking prescription opioids.

Just over a year later, in November 2009, Carol Ann Bosley died of an overdose.

“I couldn’t come back into this house for three or four weeks,” after discovering his wife dead on the couch after an overdose, said Bosley. “I couldn’t sleep here. It’s the most horrible thing I’ve been through in my life.”

A few weeks after she died, Roy Bosley said he was surprised to find that her death certificate listed “suicide” as the cause of death.

He said he broached the issue with the medical examiner, and was stunned by his response.

“I said, ‘Why did you label it suicide?’ And he says ‘Well, I called Dr. Webster. He told me that she committed suicide.’”

Webster denied repeated requests by CNN to validate Bosley’s claims; his spokesperson reiterated that he does not discuss patient cases.

About a month later, the cause of death on Carol Ann Bosley’s death certificate was changed from “suicide” to “not determined.”

Dr. Edward Leis, the medical examiner who performed Carol Ann Bosley’s autopsy, denied having a conversation with Webster about her case.

He said the original determination of suicide was made based on elevated levels of prescription oxycodone and alprazolam (a painkiller and a sedative) in Carol Ann Bosley’s system when she died.

Leis said the amendment to her death certificate – although changes like that do not happen often – took into account additional information that Bosley provided about his wife’s state of mind before her death.

Similar to Carol Ann Bosley, after years of addiction, Tina Webb stopped taking painkillers. But it only lasted a month. Soon she was back at Lifetree asking to be prescribed opioids.

Reluctantly, Bruce Webb said he participated in her new treatment plan, which involved him helping to administer his wife’s medication.

What he did not know – what he said the staff at Lifetree never told him – is that Tina had become “opiate naive.” Her body could not handle pain medication at the level she was previously prescribed.

“They put her back on the same drugs, the same dose,” said Webb, echoing an allegation in the lawsuit he filed against Webster and Lifetree. “So she took six pills that day (she died). That’s all it took.”

While her two young sons played outside in the yard in September 2007, Tina Webb lay in her bed, dead after an overdose.

“I come home from work and the boys meet me outside, say, ‘Mom won’t get up,’” said Webb. “I go upstairs and with the light in the room fairly dark, I knew. I went up closer to her, touched her, she was cold, stiff.

“I just sobbed. I just sobbed like a baby.”

Questions linger

In depositions and in response to lawsuits brought against him, Webster has denied all allegations against him and his clinic.

A law enforcement source said it is unclear when the DEA’s investigation will conclude, and whether it will find evidence of wrongdoing by Webster.

If charges are ultimately filed against him, at worst Webster could face a suspension of his DEA registration, and thus his ability to prescribe controlled substances.

Even as allegations swirl around him, Webster has said he supports – even advocates – alternatives to opioid-based therapy, except when it is used in a small subset of patients who benefit from it.

“Sadly, the number of people with chronic pain has exploded over the last 10 years, escalating the problem of pain to an urgent, national crisis, one which demands a direct and honest dialogue that currently is not happening,” Webster’s statement said. “We need safer, more effective therapies and, ultimately, need to replace opioids as a treatment method so these tragedies never happen.”

Despite the allegations against him and his clinic, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the organization headed by Webster, stands behind him.

“(Dr. Webster) is one of the country’s foremost experts on the treatment of pain,” said AAPM Executive Director Philip A. Saigh Jr. in a statement. “He has been a tireless advocate for the millions of Americans who suffer from chronic pain that is so debilitating that they cannot engage in normal daily activities.”

“Our staff included as many as 15 clinical professionals who treated more than 21,000 (patients) over more than 20 years,” said Webster in his statement. “We treated some of the most difficult and complicated situations with people in pain and saw to it that all patients received the highest standard of care. “

Bosley and Webb have a starkly different view of Webster. They say he and his staff failed their wives.

Even years after their deaths, questions linger for both men; and the pain still smarts.

It has been particularly difficult for Webb, who has tried to make sense of the loss for his two sons.

He said, “…the heartache, the pain, the sleepless nights. It continues on. It’s not done.”