Editor’s Note: Frida Ghitis is a world affairs columnist for The Miami Herald and World Politics Review. A former CNN producer and correspondent, she is the author of “The End of Revolution: A Changing World in the Age of Live Television.” Follow her on Twitter @FridaGhitis.

Story highlights

Kim Jong Un accused his uncle of betrayal; North Korea media say uncle was executed

Frida Ghitis: This tactic used by Saddam Hussein in consolidating his power

Ghitis: Kim's uncle was accused of living in depravity; now, the military is in charge

Kim is sending a brutal message that he will punish any whisper of dissent, Ghitis says

The chilling images from North Korea brought back memories from one of the most disturbing and important moments of none other than Saddam Hussein’s tactics for establishing his iron-clad rule of Iraq. The young North Korean leader, Kim Jong Un, it appears, has learned from the most ruthless and long-lasting of modern dictators.

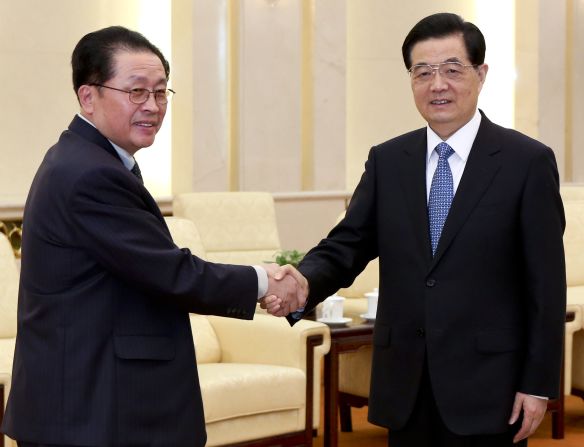

On Monday, North Korea’s citizens saw what would have seemed impossible just a few months ago: The man who had stood at Kim’s side since he came to power, his uncle Jang Song Thaek, publicly humiliated in a shake-up that signaled a fierce power struggle and sent a stern message to the country and the world.

The televised footage showed what unfolded during the meeting of the party’s Central Committee, reportedly the day before. In a room of stunned party members, two uniformed soldiers grabbed Jang – until recently the country’s second most powerful man – and took him away after he was accused of betraying Kim and the revolution.

Just a few days later, on Thursday, the North Korea government-controlled Korean Central News Agency reported that Jang had been executed for betraying the regime: “Despicable human scum Jang, who was worse than a dog, perpetrated thrice-cursed acts of treachery in betrayal of such profound trust and warmest paternal love shown by the party and the leader for him.”

Decades-old grainy black and white images from Iraq tell a similar story of power and intrigue whose consequences are now well-known.

On July 22, 1979, during a meeting of Iraq’s Baath Party, the names of 60 top party leaders labeled traitors were read as, one by one, the terrified men were removed from the hall. That footage was also distributed widely – a sign to all that Hussein would let no one stand in his way, instilling fear even among the most powerful in the country. It was a moment that as much as any other cemented Hussein’s rule for almost a quarter of a century.

In keeping with the totalitarians’ textbook, the North Korean regime denounced Kim’s uncle in language that would be familiar to those who have lived under the worst dictatorships.

The masterpiece of totalitarian prose, published for all to read in the state media, accused Jang of leading a “dissolute and depraved life.” It condemns him for pretending to support Kim while “dreaming different dreams,” and living a life of corruption, ambition, drug use, “wining and dining at back parlors and deluxe restaurants,” as well as “gambling in foreign casinos at the party’s expense” and being “affected by the capitalist way of living.”

Kim’s uncle, the regime charges, was “behaving against the elementary sense of moral obligation and conscience of a human being.” Most of all, Jang – married to the sister of Kim’s late father, former leader Kim Jong Il – is accused of planning to challenge his nephew and undermine him as “unitary center” of the state.

It’s a stunning ledger of charges and one that makes no effort to conceal there is a power struggle in North Korea.

Tellingly, the accusations speak of a Jang Song Thaek “group,” which suggests the purge is far from over. There have already been reports that a couple of Jang associates were executed.

State media has followed the reports with a scrubbing of the files. Jang is being erased from the records. The man who stood at Kim’s side when his father died is being Photoshopped out of existence.

All mentions of him – except for the condemnations – are disappearing from the website of the Korean Central News Agency. And every photograph is now suddenly, and not-so-mysteriously, free of his image. He has even been deleted from a recent documentary about Kim Jong Un.

The question is what comes next: What does this mean for the millions of North Koreans living under Kim’s brutal rule? How does this execution and purge affect nuclear-armed North Korea’s behavior on the global stage?

Jang was known as something of a reformer, although that term must be viewed within the context of the totalitarian regime. He supported limited market reforms and reportedly opposed Pyongyang’s nuclear test earlier this year – both positions that put him at odds with the military. There is little doubt that Jang’s execution strengthens the military’s hand.

The experience from Iraq suggests that a reign of fear among the powerful serves only to entrench the harshest policies. High-ranking officials, worried about appearing weak or disloyal, will be more reluctant to suggest reforms that loosen the regime’s grip.

That is dismal news for those who live in a state that is the world’s worst violator of human rights. A new report from Amnesty International says as many as 200,000 North Koreans, including children, the elderly and generations of families live in prison camps where they routinely endure torture, starvation and worse. Life outside the camps is also subject to harsh conditions for most North Koreans.

When the younger Kim came to power in 2011 after his father died, some held hope that his time living in Switzerland had instilled reformist instincts, expecting he would moderate domestic policies and undertake more conciliatory actions toward the rest of the world.

But so far, he has proven as defiant and inflexible as his father and grandfather. In a major crisis a year ago, he launched long-range missiles and later detonated a nuclear weapon and then threatened a nuclear attack against the U.S. and South Korea.

Kim may now want to prevent anyone from taking advantage of turmoil in Pyongyang with another show of force.

It is not clear what exactly caused the high-level purge. The military might have triggered and won the clash with Jang. Some suggest Kim may now be a figurehead in a military-led regime, but he already reshuffled the military command. He appears to be in control.

More likely, however, Kim is consolidating power, much like Hussein did in 1979. He is building his own inner circle of trustworthy loyalists and daring anyone to defy him. The young heir who rose to power two years ago under the protection of an experienced uncle is sending notice that he is not a child any more. The dictator is all grown up and settling in for a long time in power.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Frida Ghitis.