Story highlights

- U.S. pulled support of Iran's nuclear program during Islamic Revolution

- Since the revolution, the West has worried Iran may produce atomic weapons

- France, U.S., UK, Russia, China, Germany -- and Iran -- have been negotiating deal

- The deal slows Iran's program in exchange for lighter sanctions

When it comes to Iran and the West, the relationship has been convoluted for decades. And this deal is no different. After days of negotiations, six world powers and Tehran reached an agreement that calls on Iran to limit its nuclear activities in return for lighter sanctions. It's complicated politics coupled with complicated science.

Here's a quick primer to get you up to speed.

How did Iran's nuclear program start?

The United States launched a nuclear program with Iran in 1957. Back then, the Shah ruled Iran and the two countries were still friends. With backing from the United States, Iran started developing its nuclear power program in the 1970s. But the U.S. pulled its support when the Shah was overthrown during the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

Who are these 'six world powers'?

The talks involved the P5+1 group comprising diplomats from the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council: U.S., UK, France, Russia and China, plus Germany -- and of course Iran. The group has been meeting in Geneva for days in hopes of reaching a diplomatic solution.

Is Iran the only nation with a nuclear program?

No.

Eight nations are known to have nuclear weapons, including all the P5 countries. Nearby Israel has always declined to confirm whether it has any, although the Federation of American Scientists estimates it has about 80 atomic weapons. But since the 1979 revolution, concerns have escalated that Iran could enrich uranium and make atomic weapons. Iran has maintained its nuclear program is only for peaceful purposes.

Why have the other nations not faced as much scrutiny?

For nations such as India and Pakistan, no action was taken partly because they never signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. "There was very little that the U.S. could've done to stop Pakistan," says Mark Hibbs, a nuclear policy expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Iran, on the other hand, signed the treaty. And as a result, its program was put under the spotlight. In addition, the International Atomic Energy Agency had information suggesting Iran conducted activities it hasn't declared in the past.

Why is Iran's nuclear program considered such a threat?

Since its revolution, the West has worried Iran could use its nuclear program to produce atomic weapons using highly-enriched uranium. A decade ago, nuclear inspectors from the international agency announced they had found traces of highly-enriched uranium at a plant in Natanz. Iran temporarily halted enrichment, but resumed enriching again in 2006, insisting enrichment was allowed under its agreement with the IAEA.

Enough with the background. Let's talk about the deal that was reached.

It's more of an interim agreement before the deal. Described as an initial, six-month deal, the White House says it includes "substantial limitations that will help prevent Iran from creating a nuclear weapon." In short, it slows the country's nuclear development program in exchange for lifting some sanctions while a more formal agreement is worked out.

It's not permanent, so why is it a big deal?

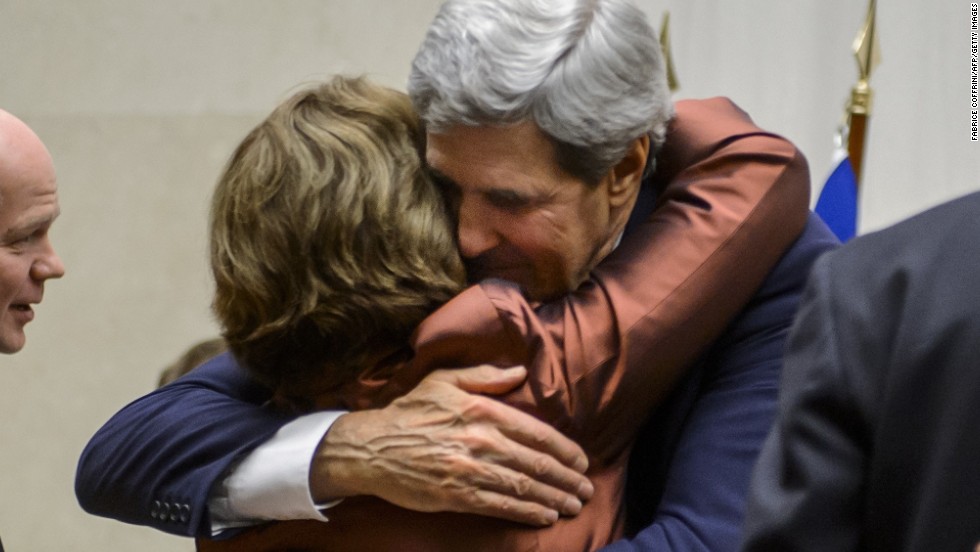

For years, Iran and Western powers have left negotiating tables in disagreement, frustration and open animosity. But the diplomatic tone changed after Iran's election this year, which saw President Hassan Rouhani take over. "For the first time in nearly a decade, we have halted the progress of the Iranian nuclear program," U.S. President Barack Obama says.

What about the stockpiles Iran already has?

As part of the deal, Iran will be required to dilute its stockpile of uranium that had been enriched to 20%. While uranium isn't bomb-grade until it's enriched to 90% purity, "once you're at 20%, you're about 80% of the way there," Hibbs says. The deal also mandates Iran halt all enrichment above 5% and dismantle the technical equipment required to do that. Before the end of the initial phase of the deal, all its stockpiles should be diluted below 5% or converted to a form not suitable for further enrichment, the deal states.

Why 5%?

Iran consistently says it's enriching uranium and building nuclear reactors only for peaceful civilian energy needs. Nuclear power plants use uranium that is enriched to 5%. It's the fuel that the plants use to generate electricity.

What else will Iran have to do?

Iran would also have to cut back on constructing new centrifuges and enrichment facilities, and freeze essential work on its heavy-water reactor under development at Arak. That facility could be used as a source of plutonium -- a second pathway to a nuclear bomb. The reactor under construction southwest of Tehran had been a sticking point in earlier negotiations.

What's a centrifuge?

It's a mechanism used to enrich uranium.

How will we know Iran is living up to its end of the deal?

Iran is expected to provide daily access to inspectors from the international agency, IAEA. The inspectors will be expected to visit centrifuge assembly and storage facilities, uranium mills and the Arak reactor, among others. The P5+1 and Iran will also form a joint task force on the issue.

What if it doesn't fulfill its commitment?

The international community will add more sanctions -- and pressure.

What's in it for Iran?

Billions of dollars.

As part of preliminary steps, the world powers involved in the talks will provide "limited, temporary, targeted, and reversible relief to Iran."

The deal calls for no new nuclear-related sanctions in the six-month period if Iran keeps its end of the bargain. The world powers will also suspend sanctions on various items, including gold and petrochemical exports. That suspension will provide Iran with about $1.5 billion in revenue, according to the White House. Sanctions relief will also target other areas, including government funds from restricted Iranian accounts for its students in other countries.

But the White House says the $7 billion in total relief is just a small fraction. "The vast majority of Iran's approximately $100 billion in foreign exchange holdings are inaccessible or restricted by sanctions," it says.

What's not in the deal?

A better deal would have included Iranians shipping out their highly enriched uranium to be converted elsewhere, says Aaron David Miller, vice president of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. "It would have been better ... if Iran had much more of their nuclear infrastructure put out of use. But that's the deal they got."

How did the sanctions come to be?

Seven years ago, the U.N. Security Council passed sanctions against Iran for failing to suspend its nuclear program. Sanctions that initially targeted Iran's nuclear capability expanded to include bans on arms sales, Iranian oil and certain financial institutions, including the country's central bank. This has crippled its economy and made Iran a pariah in the international community. Oil revenues have plummeted, and the local currency had dropped 80% in value by 2012. Iranians have faced spiraling inflation and layoffs.

Why isn't Israel applauding the deal?

The two nearby countries and archrivals have been at each other's throats for years. Israel says it has the most to lose if Iran develops a nuclear bomb. It has repeatedly warned the West to tread warily when dealing with Tehran. And Israeli lawmakers are not happy that their greatest ally, the United States, has disregarded their warning and struck an interim deal with Iran. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu called the agreement a "historic mistake" that his country isn't bound by.

So much tension between Iran and Israel, why?

It wasn't always this way. After the birth of Israel in 1948, the two nations enjoyed a "honeymoon" that lasted until just before the 1979 revolution, says David Menashri, professor emeritus of Tel Aviv University. Israel even supplied weapons to Iran to help it fight their common enemy, Iraq. But the Islamic revolution that overthrew the Shah marked a turning point. The Islamic republic, led by Shiite clerics in the predominantly Shiite nation, saw Israel as an illegitimate state with no right to exist, certainly not amid Muslim nations. Years later, Israel began to regard Iran and its support of global terror as a chief threat. Those concerns escalated when international inspectors found traces of highly enriched uranium at a power plant in Iran.

Who else is unhappy?

Saudi Arabia. It's a majority Sunni country. Iran is majority Shiite. Saudi Arabia, like Israel, is troubled by Iran's growing clout in the Middle East. "The Saudi government has been very concerned about these negotiations with Iran and unhappy at the prospect of a deal with Iran," a Saudi government official who is not authorized to speak to the media told CNN.

So, will this interim deal work?

There are no perfect agreements. And the success of any interim deal will be measured "in months and years, not in minutes," says Karim Sadjadpour of the Carnegie Endowment. Whether Iran is serious about mothballing its nuclear ambitions remains to be seen. There may be sizable obstacles that aren't yet apparent. There are certainly aspects where the deal stopped short. For now, Miller says, don't break open the champagne bottles just yet.