Story highlights

Ted Turner founded CNN in 1980. It was the first global 24-hour news network

Turner turned 75 on November 19; he is involved in philanthropy now

Turner has paid $965 million toward a $1 billion pledge to the United Nations

He is also the second largest landowner in North America, with 2 million acres

What will matter most about Ted Turner’s life story when they roll the final credits?

That he started the first 24-hour news network? Built a fortune once worth $10 billion? Was Time magazine’s “Man of the Year”? Received a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame? Made The New York Times best-seller list?

Maybe it was that time he raced a sailboat faster than anyone else. Or the year his baseball team won the World Series. Impressed yet? Did you know he had a president for a fishing buddy and won the heart of a movie star?

Turner turned 75 on November 19 and yes, he has done or been all of these things. There’s also his “Captain Outrageous” side. He kept a pet alligator, compared rival Rupert Murdoch to Hitler and called Christianity “a religion for losers.” He stuck his foot in his mouth – and apologized – too many times to count.

But there’s more to Turner than the swashbuckling sportsman, Forbes list billionaire (No. 260, $2.1 billion) or infamous “Mouth of the South.” After he rose to great heights, he fell to earth with a humbling thud and his better self emerged as a humanitarian and large-scale philanthropist hell-bent on setting a good example for other billionaires. As Turner sees it, what’s the point of making billions if you can’t give most of it away?

So he has so far made good on $965 million of his $1 billion pledge to the United Nations. He has worked for more than a decade to protect endangered species, grasslands and oceans, championed energy conservation, railed against global warming, fought to rid the world of nuclear weapons – the do-gooder list goes on and on.

Check out Ted Turner’s website

He even helped bring back an American icon, the buffalo, from the threat of extinction. Always the entrepreneur, he saved bison by convincing people to eat them – at his 44 Ted’s Montana Grill restaurants, of course.

Why Ted Turner is big on bison

Even considering all his accomplishments and feats of derring-do, Ted Turner is only human. And so, with three-quarters of a century in his rear-view mirror, he’s also thinking about the things ordinary people think about as the sun goes down.

You can be a billionaire or a bum, win sailing’s biggest prize or swab decks, own a television network or have trouble paying the cable bill: By the final curtain, life boils down to a few simple things.

Did I make my Mama and Daddy proud?

Am I loved?

Will anybody remember me?

Do I get into heaven?

‘Somebody’s out there’

It doesn’t seem to matter that for most of his life Turner swore that God and religion are so much hooey, and there’s no way he could ever settle down with just one woman. He seems more open now to the possibility that something larger than himself is out there – a higher power, perhaps, or his one true love. Maybe even both.

A conversation with Ted Turner on a recent Tuesday morning revealed a couple of surprises:

A man who has been virulently anti-religious admitted he tosses off a little prayer now and then, hoping there’s “somebody out there” to hear it.

And, a man who has been married and divorced three times and keeps four girlfriends in a “loose” weekly rotation believes people are meant to find a lifetime soul mate. He thinks he still has time to find his.

Ted Turner believes you only get one shot – having seen no proof of past or future lives – and so he has gone at it full throttle, cramming in countless incarnations as a sailor, rascal, ad man, team owner, media mogul, gadfly, outcast, philanthropist, rancher and restaurateur. Besides the three ex-wives, there are five children, a slew of grandchildren and 28 properties across the United States and in Argentina.

As the milestone 75th birthday approached, CNN spent time with Turner on his Montana ranch, at his early childhood home in Ohio and at his penthouse in Georgia. Dozens of his friends, associates and family members were interviewed. Many will gather at a gala in Atlanta’s tony Buckhead neighborhood at the end of the month to help him celebrate.

Turner talked at length with anchor Wolf Blitzer, whom he has known for many years, and granted this reporter a few snippets of his time, including a half-hour interview at his office in Atlanta. He completed it in 23 minutes.

Turner said he is tired and he is hard of hearing, but he continues to stay in constant motion. He walks more slowly now, but his eyes are keen and his jaw is square. He doesn’t suffer fools, and any woman he hasn’t met before can expect a thorough visual once-over. For a powerful billionaire, he is surprisingly solicitous, taking pains to ensure that visitors have everything they need.

In conversation, a name might elude Turner for a minute or two, but if he moves off a subject at the beginning, he remembers to return to it. He can be restless and impatient, but he has always been that way, and one must work hard not to bore or annoy him. It is some small consolation that he refrained from calling his CNN questioner “dummy” or “silly,” as he has done with others.

Turner still strides into a room with boisterous confidence and a loud guffaw that’s like a verbal backslap. At a recent board meeting in the offices of Turner Enterprises Inc., his cluster of companies and charitable foundations, he greeted news that his restaurants were making money by crowing: “Winning’s great, losing sucks.”

Wolf Blitzer: 5 things I learned from Ted Turner

He still punctuates his thoughts with pauses that have a drawl all their own:

Aaaaaaaahhhhhh.

Turner has mellowed; if he’s not exactly warm and cuddly, he is a kinder, gentler Ted. The man who had little quality time for family while his five children from two wives grew up now sends them daily newsletters. If he wasn’t a particularly attentive father, he’s a hands-on grandfather.

He seems genuinely touched that people still care about what he has to say. Especially if they work for his baby, CNN.

‘Dear son, I fear you are rapidly becoming a jackass’

Had he been coddled and cooed over, Ted Turner might have become an underachiever. But what drives him to this day is rooted in boyhood events that in hindsight seem cold, even cruel. He was packed off to boarding school at the tender age of 4, and he spent most of his formative years at military schools. His relationship with his father, Robert Edward Turner II, was difficult, some would say abusive, although he does not describe it that way.

The boy idolized the man, but the man had a weakness for alcohol, was prone to mood swings and often treated the boy harshly, trying to make him tougher. When the boy was defiant, his father beat him with the leather strap used to sharpen a straight razor, or with a wire coat hanger.

“It wasn’t dangerous or anything like that,” Turner recalled. “It just hurt like the devil.”

On one occasion, the father turned the tables on his son, ordering him to use the strap on him. Ted, tears rolling down his face, couldn’t do it.

The verbal lashings no doubt hurt just as much, if not more.

Turner remembers his mother as “a nice lady” and said he loved her dearly, but his father dominates any conversation about his early years. In a book about his life, he described how she stood outside the bedroom door and begged his father to stop spanking him.

Even as a child, Turner loved nature and the outdoors. His first word was “pretty,” he was told. Yet at 4, he suddenly found himself alone, in a grim boarding school with no grass, only blacktop for a playground, while his father served in the Navy during World War II.

The experience left him with lifelong abandonment issues, and Turner acknowledges in “Call Me Ted,” a 2008 book about his life, that he is not comfortable when left in his own company. He compulsively fills his schedule so he doesn’t have to sit still or be alone. His former wife, Jane Fonda, has said he lives his life as though he is trying to outrun his inner demons.

After his father came home from the war, Ted spent even more time away, at strict Southern military schools. He liked learning about military strategy and all the battles, and his early education informed his thinking. His lifelong motto became, “Hope for the best, but prepare for the worst.”

His father wanted him to go to Harvard, but Ted didn’t make the grades. He did get into another Ivy League school, Brown, but left before graduating. Although there were some disciplinary scrapes – he set fire to a fraternity parade float and was caught with a girl in his room – his father cut off his tuition because he disapproved of his major.

The elder Turner believed studying the classics was a waste of time, as he made clear in a letter. An excerpt:

My dear son,

I am appalled, even horrified, that you have adopted Classics as a major. As a matter of fact, I almost puked on the way home today. … I am a practical man, and for the life of me I cannot possibly understand why you should wish to speak Greek. With whom will you communicate in Greek? … I think you are rapidly becoming a jackass, and the sooner you get out of that filthy atmosphere, the better it will suit me. … You are in the hands of the Philistines, and dammit, I sent you there. I am sorry.

Devotedly,

Dad

Turner shared the letter anonymously with the school paper in an act of defiance. But before long the money ran out and he was back home in Georgia, working for his father’s billboard company. He was put in charge of the Macon office.

He was just 24 when his father shot himself and died in the upstairs bathroom at the family’s home near Savannah, Georgia. It was March 5, 1963, and the elder Turner was under the influence of alcohol and pills, battling depression and worried he had overextended himself with a $4 million purchase that expanded his company, Turner Outdoor Advertising, into the South’s largest billboard company.

“He went against everything he taught me: ‘Be courageous and hang in there,’” Turner said.

Suddenly in charge of his father’s company, he buried his shock and grief in work. But he wasn’t content to push other people’s products forever. In 1970, he bought his first television station. Six years after that, he beamed the signal up to a satellite and it became cable TV’s first superstation.

In September 1977, Turner and the crew of the Courageous won the America’s Cup. Three years later – on June 1, 1980 – CNN, the first 24-hour global news channel, went live and has been on the air ever since. On both occasions, and at later ones, people close to him noticed that Turner paused for a moment amid the celebration as if to say, “Look at what I did, Dad.”

No matter how successful he became, Turner was still trying to prove himself.

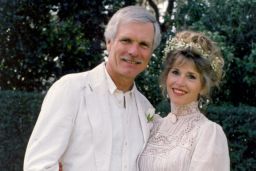

Fonda recalled how she cried when he told her about his childhood on their second date. They were driving around his 60,000-acre ranch in Montana, and he was passing the time, talking as he drove. Tears ran down her face.

“He literally couldn’t understand why I was crying when he told me stories about what his father did to him,” she said. “Children can’t blame their parents. ‘It’s always my fault; it’s being done for my own good. I must not be good enough.’”

The cruelty he endured gave him an endearing boyish quality, she said. “And it’s wonderful and loving and you can’t help but love it. But there’s always a sadness to it because it means there was something that stopped early on.”

‘I would never love anyone like I love him’

Former President Jimmy Carter and Ted Turner were fishing in the middle of a lake in northern Florida early one morning in February 1989 when the conversation took a gossipy turn.

It seemed to Carter that Turner was thinking out loud. He began with a question but ended with more of an announcement:

Did you hear Jane Fonda is divorcing Tom Hayden? I think I’ll ask her out.

“I think I was the first person he ever mentioned that subject to,” Carter said.

Sure enough, Turner called Fonda that very same day. She shot him down.

“I was in the middle of a full-blown nervous breakdown,” she recalled. “I couldn’t speak above a whisper. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t walk fast. I mean, I was in a very sad place. And the day the announcement appeared in the paper, the phone rang, my housekeeper answered the phone and said, ‘Ted Turner’s on the phone.’ I had met him once, very briefly, but you know, I didn’t really know him. I pick up the phone and hear this booming voice:

‘Is it true?’

Is what true?

‘You and Hayden, are you divorcing?’

Yes.

‘You wanna go out?’

“I said, Ted, uh, thank you for asking, but I’m actually in the middle of a nervous breakdown and I don’t think I can go out. Call me in six months,” Fonda recalled.

“And he said, ‘I know exactly how you’re feeling. I just broke up with my mistress. That I left my wife for.’

“And I thought, ‘This guy is crazy.’ This is not what I want to hear right now.”

She told him to call back in six months. He circled his calendar, and called back six months later – to the day.

Carter had given Turner a little unsolicited advice: “I said all you gotta do is be nice.”

They finally went out to dinner in Los Angeles. When Turner picked her up, Fonda was taken aback by the way he leered at her. “His eyes, I felt like he was devouring me,” she said. “It was the most palpable sexuality that I had ever experienced.”

At the restaurant, she recalled, he kept getting up to go to the men’s room. She assumed he was snorting cocaine or making other dates. Only later did she learn that he urinates frequently when he is nervous.

“At first they didn’t get along at all,” Carter recalled. “In fact, they didn’t like each other. I heard this from both of them. It was months later before they decided to try again. And they evolved into one of the nicest romances that I’ve ever known about.”

They stayed together for 10 years and became one of the nation’s most storied couples. When they split, his anger at her conversion to Christianity was blamed, but the truth was more nuanced. She simply could no longer take a back seat to his larger-than-life personality or sustain his need for her constant companionship as they shuttled between his 28 properties. She was pushing 60 and no longer interested in living out of a suitcase.

She said they’d still be together if he hadn’t required her constant presence.

“I would never love anyone like I love him,” she said. “But I just couldn’t keep moving in his world, along the surface for the rest of my life. I knew that I would get to the end of my life and regret not doing the things that I also needed to do for me.”

He was devastated when she left him and their divorce came during the worst time in his life. By the time the divorce papers were signed and finalized, he had been pushed out of the newly merged AOL Time Warner and lost control of Turner Broadcasting, CNN and the Atlanta Braves. He stayed on the board until 2003, but the merger was a boondoggle and his fortune, consisting mostly of company stock, was hemorrhaging – more than $7 billion in three years.

“I lost Jane. I lost my job here. I lost my fortune, most of it. Got a billion or two left. You can get by on that if you economize,” he told CNN’s Piers Morgan in May 2012. He said he was “brokenhearted.” He tried to win her back, but it was obvious the relationship was beyond repair. “We were so far apart philosophically, we couldn’t do it.”

Even as Fonda exited, Turner had an old flame waiting in the wings. Soon, he had a new romantic arrangement: a “loose” rotation of four girlfriends, each of whom he sees for about a week at a time. Some of them are happier about the situation than others, he acknowledged, but “we’re still doing it.”

He agreed that Fonda “probably” was the great love of his life and that he still hasn’t gotten over her. He said he probably never will.

“When you love somebody and you really love them, you never stop loving them, no matter how hard you try,” he told Morgan. “You can’t – and there’s nothing wrong with that. That’s good.”

Fonda still carries a torch for Turner as well.

Some friends root for a reconciliation. The two maintain a close friendship, speaking about once a month. They show up for each other at big events. Turner was at Fonda’s side at a recent fundraiser in Atlanta for her charity, the Georgia Campaign for Adolescent Power & Potential. He sported a fresh haircut and she fussed over him, gently brushing stray hairs from the shoulders of his tux.

“Just because people get divorced doesn’t mean they stop loving each other,” she said. “It may be hard for two people to live together, but I can’t ever forget the reasons that made me fall in love with him.”

Turner explained that he has “loved many people” but only been “in love” twice – once with Fonda and once with someone he won’t name. Being “in love” implies permanence, he said – something he hasn’t experienced in his relationships.

Is that even possible? Is it realistic to expect love to last forever?

“I think it does for some people,” he said. Finding a mate for life, he added, “is a worthwhile goal.” It’s just one this goal-oriented man hasn’t realized, at least “not yet.”

Hope springs eternal in Ted Turner’s world.

‘Wave a white flag and I’ll come running’

Ted Turner can see the giant red letters – CNN – from the windows of his penthouse atop the office building he owns in Atlanta, across Centennial Olympic Park. He often jokes that he’s waiting for a signal.

If the 24-hour news network he launched in 1980 ever needs him, Turner said, “Just wave a white flag and I’ll come running.”

So far, nobody’s waving any flags, nobody’s running.

A decade has passed since Turner “left the building,” as the saying goes. He was fired from the company he created by people who bought it and then sold it to somebody else. But even all these years later, visitors taking the CNN tour ask where Ted is.

Longtime employees still tell stories about Turner, who lived for a decade in his office in the CNN building before moving with Fonda into a penthouse apartment on the 14th floor. They say he’d sometimes saunter into the newsroom wearing just a bathrobe and pour himself a cup of coffee. The penthouse stands empty, but old-timers talk about Turner like he’s haunting the building.

Nobody remembers the names of the people who pushed him out.

“Is that so?” Turner drawled, a smile creasing his face. Sure, it’s gratifying, but he insisted he has moved on.

Nowadays, Turner is a committed environmentalist. The brash media mogul who used to park a red Ford Taurus in the CNN garage gets around in a more fuel-efficient Prius hybrid. At his Turner Enterprises building a couple of blocks away, he has erected solar panels over his parking lot to power his penthouse, offices and restaurant, where the toilets are low-flush and the straws are made of paper, not plastic.

He still watches CNN – “too many in-depth stories about the murder of the day” for his taste – but other things consume his attention. Endangered species. Population growth. Nuclear proliferation. The United Nations.

Bad-boy Ted has turned do-gooder and he has unfinished business.

“I would like to see the world rid of nuclear weapons,” he said. “And I would like to see us make the changes in our behavior so we don’t destroy the environment, because if we destroy the environment, we destroy ourselves. I’d like to see us human beings still here 1,000 years from now living in peace and harmony with nature. That’s what I’m working on.”

The philanthropic streak was always there, but it began to move to the forefront in 1997, the year after he sold Turner Broadcasting to Time Warner for $7.3 billion. He pledged $1 billion to the United Nations. But making good on that pledge took a while longer than he had anticipated, thanks to the beating his fortune took after the 2001 merger with AOL. When it was over, he was still a billionaire, but just barely. He skulked off to lick his wounds, raise bison, and do good deeds.

As of September, Turner has given $965 million to the United Nations, according to Forbes, the business magazine. Turner said earlier this month that the rest “is coming in the next two years.” His five children – Rhett Turner, Laura Turner Seydel, Jennie Turner Garlington, Teddy Turner and Beau Turner – serve on the board of the Turner Foundation. Other foundations include his United Nations Foundation, Nuclear Threat Initiative, Captain Planet Foundation and the Turner Endangered Species Fund.

Turner doesn’t do anything in a small way, including reinventing himself. He is the second biggest landowner in North America, with 2 million acres spread over 28 properties, including 17 ranches in Nebraska, Kansas, Montana, New Mexico and South Dakota, as well as in Argentina. The first of his Ted’s Montana Grill restaurants opened in 2002, and now there are 44 in 16 states. He has managed to bring bison back from the brink of extinction; he has the world’s biggest bison herd, with 55,000 head.

At a recent board meeting for his restaurants, Turner learned that an early blizzard had killed 70,000 head of cattle in the Western states. But while cattle were freezing and starving, bison were doing just fine because their winter coats had grown in by late August and their humps made it easier to graze in deep snow.

Turner suggested sending a few bison calves out to the cattle ranchers who were hit hardest by the storm. He didn’t see it as charity. He viewed it as a smart business move.

Half a century ago, his father’s suicide thrust a $1 million billboard company into his hands. He has often said that his father, who was 54, ran out of things to work toward. As a result, Turner has been driven – relentlessly moving forward, never looking back.

The Mouth of the South is nowhere to be found. His voice can still be heard across several rooms, but the brashness is long gone. He is still witty, but no longer flippant. Sharp, but no longer combative. And, past descriptions to the contrary, there seems to be some small measure of reflection.

Ted Turner is starting to contemplate his own mortality. And his legacy.

Years ago he joked, “I know what I’m having ‘em put on my tombstone: ‘I have nothing more to say.’” He also joked that he’d like Willie Nelson to sing at his funeral. His request: “To All the Girls I’ve Loved Before.”

These days Turner talks instead about being cremated and having his ashes scattered over his favorite ranches.

It’s better for the environment.

‘I don’t want to go to hell’

Even though he is a son of the Bible Belt, Ted Turner and God haven’t been on the best of terms. Despite his strong stance against religion in the past, he’s not an atheist. He’s an agnostic, trying to make sense of it all – his way.

He revised the Ten Commandments, which he considered outdated, coming up instead with his Eleven Voluntary Initiatives, which he printed on cards small enough to carry in a wallet. He tossed out the commandments that struck him as outdated – a host of the “thou shalt nots,” particularly the one banning adultery. “People have had a lot of fun breaking that one. I know I did.”

Turner’s initiatives focus instead on caring for the Earth “and all living things,” treating others with dignity, looking out for the poor, having no more than two children, and avoiding the use of toxic materials.

As with most things, Turner’s rocky relationship with his supreme being, assuming there is one, stems back to childhood.

When he was very young, he dreamed of being a missionary. Then his little sister, Mary Jean, got sick at age 12. He watched as she suffered terribly from a rare form of lupus and complications that left her with brain damage and screaming in pain for years until she died. It shook his faith profoundly.

He could not understand why any God would let an innocent suffer.

“She was sick for five years before she passed away. And it just seemed so unfair, because she hadn’t done anything wrong,” he said. “What had she done wrong? And I couldn’t get any answers. Christianity couldn’t give me any answers to that. So my faith got shaken somewhat.”

He once walked into the CNN newsroom on Ash Wednesday and, spotting several staffers with smudges on their foreheads, blurted out, “What are you? A bunch of Jesus freaks? You ought to be working for Fox.”

He has said famously that “Christianity is a religion for losers,” even though some of his closest friends have a deep and profound faith.

“He knew I was a Christian when he said that,” said former President Carter. “Ted had a tendency to say things like that just to be provocative. And to stir people’s interest. But later he retracted that statement.”

Carter continues to hope his friend will someday “have a profound religious experience.”

Turner said he respects the position of his religious friends, but he’s a skeptic by nature. He described himself as an agnostic, although as a younger man he was an atheist, and virulently anti-religious. These days, he keeps the door open a crack. He allows for the possibility.

“When I have a friend that’s dying of cancer, I say a prayer for them,” he said.

To whom does he direct the prayer?

“Whoever is listening.”

Fonda said she believes Turner’s childhood traumas left him so protective of himself that he had trouble opening up emotionally. But, she said, he does want to get into heaven. And, she said, he’s a shoo-in.

Finally, with our 23 minutes with Turner ticking down, we’ve gotten his full attention. We let him in on what Fonda has told CNN about his heavenly prospects:

“Given his childhood,” Fonda said, “he should’ve become a dictator. He should’ve become a not nice person. The miracle is that he became what he is. A man who will go to heaven, and there’ll be a lot of animals up there welcoming him, animals that have been brought back from the edge of extinction because of Ted. He’s turned out to be a good guy. And he says he’s not religious. But he, the whole time I was with him, every speech – and he likes to give speeches – he always ends his speech with ‘God bless.’ And he’ll get into heaven. He’s a miracle.”

Turner listened intently. There was a long pause. Was he tearing up? Finally, he spoke.

“She said that?”

Another long pause.

“Well, I sure don’t want to go to hell.”

Pause.

“Did she say I was gonna buy my way in?”

The old Ted Turner – the one who made billions and won the America’s Cup and the World Series and launched CNN – probably would have tried to buy his way in. But the do-gooder Ted is earning his way in by saving bison and other endangered species and fighting for the oceans and preserving 2 million acres of ranch land and standing up for women and supporting causes near and dear to the United Nations.

That Ted Turner gets into heaven, by Jane Fonda’s accounting.

He has said he “can’t see myself sitting on a cloud and playing the harp day in and day out.” So what is Ted Turner’s notion of heaven?

“Montana in the summer.”

CNN’s Elise Zeiger, Kimberly Arp Babbit and Dan Q. Tham contributed to this story.