Story highlights

Minutely detailed replica of Egyptian boy king's burial chamber opens to public in Egypt this month

Hi-tech reproduction technique involved scanning 100 million points per square meter

Monument-copying business seems to be going strong but some copies -- multiple Michelangelos and Eiffel Towers -- are less convincing

If the crowds under Paris’ Eiffel Tower get you down, try Shenzhen in China. It may not have the history of the French construction, but at least the coffee will be cheaper.

Or you could head to Berlin. Or to Las Vegas. Or several other locales with their own “Eiffel Towers.”

The replication of tourist attractions has been gaining traction in recent years.

Most recently, a Spanish company has been employed to replicate Egypt’s ancient pharaonic tombs.

Opening to the public later this month about half a mile from the original tomb in Luxor’s Valley of the Kings, the replica will be located outside the house of Howard Carter, the expedition leader who disinterred the pharaoh almost a century ago.

The reconstruction is a response to the threat posed by the hundreds of thousands of tourists traipsing through the real relic every year.

Changes in temperature and humidity caused by their presence in the burial chamber have caused the striking plaster-painted murals on the walls to begin crumbling away.

Tut’s new tomb

The solution was for the Madrid-based company Factum Arte to create replicas of King Tut’s and the other pharaonic tombs, including Seti I and Nefertari, as a philanthropic exercise granted permission by Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities in 2009.

The firm used minutely detailed, hi-tech techniques honed on reproductions over the past decade, including copies of the pharaoh Thutmose III’s tomb in 2003 and, more recently, of Leonardo’s painting “The Last Supper” and Caravaggio’s “Inspiration of St. Matthew.”

The replication of King Tut’s and the other royal tombs represents the company’s most ambitious project to date, as well as being the most detailed large-scale facsimile project ever undertaken, Factum Arte says.

More: World’s most beautiful bank buildings

Special 3D scanning systems were developed for the job, allowing the burial chamber to be measured at 100 million points every square meter.

The resulting 3D relief of the tomb was then reproduced on casts that were finished by hand.

“Is it exactly the same as viewing the real tomb? No. But what you can do is exceedingly high,” Adam Lowe, Factum Arte’s director, told CNN.

“You can ‘rematerialize’ the quality of the original at a normal viewing distance, so the experience is visually identical to standing in the tomb.

“It’s not an exercise in faking but [partly about] revealing the condition of the original to allow it to be monitored.”

It’s estimated that 500,000 visitors a year will visit the replica relics, the resulting funds going in part towards preserving Egypt’s real heritage sites.

Cool copy cats

Copying an ancient monument has an obvious appeal.

You get to keep the original version, as well as all the tourists – and their revenue – threatening to destroy it.

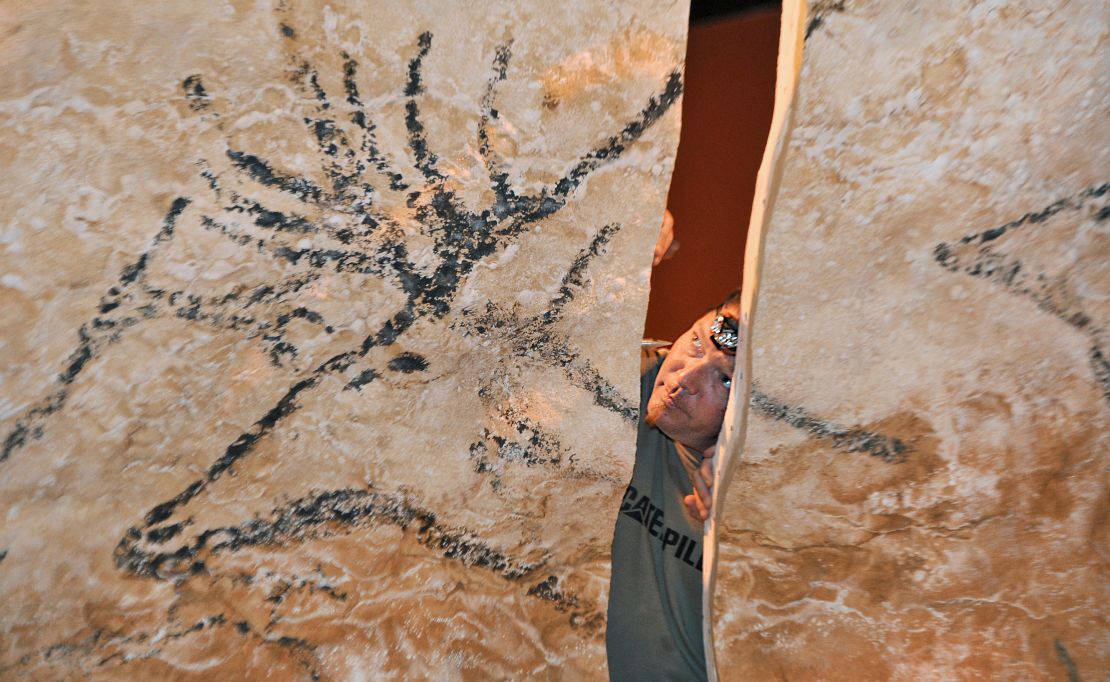

That same motivation lay behind making giant copies of the Altamira and Lascaux Caves in Spain and France, respectively, when exposure to the elements, and awestruck visitors’ breath, threatened to turn the vast galleries of prehistoric paintings they contain into mold.

The motive for replicating other tourist attractions around the world, however, seems less concerned with their heritage value.

If you think the Eiffel Tower is intimately associated with Paris, for example, you may be surprised to find more or less life-size versions of it in Las Vegas, Berlin, India, China (two, actually – in Hangzhou and Shenzhen) and Fez, Morocco.

More: 14 great literary hotels

The Taj Mahal, one of India’s great tourist sights, is no longer one of just India’s great tourist sights.

A full-sized replica of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan’s monument to his beloved third wife has sat outside the Bangladeshi capital, Dhaka, since 2008.

India has taken revenge, of a sort – it’s planning an Angkor Wat for the banks of the Ganges.

Michelangelo’s “Davids”

When it comes to art, anatomically accurate copies of Michelangelo’s “David” expose themselves everywhere from the Philippines to the U.S. state of Kentucky and Montevideo, Uruguay.

In China, the Xerox of replicating countries, you can even take home your own fairly convincing Mona Lisa or Van Gogh from the Dafen oil painting village, a neighborhood of Shenzhen famed for its fakes.

China, moreover, has recreated entire foreign locales with tourist appeal, such as London Thames Town, in Shanghai, and Hallstatt, an “Austrian” mountain village in that famous yodeling province of Guangdong.

What, you can only ask, is next – a Chinese Belgium or New Zealand?

And would anybody go?

Facsimile tourism – as good as the real thing? Let us know in the comments.