Read this story in Spanish on CNNMexico.com

Story highlights

Teen siblings who are legal U.S. residents were left alone after feds deported immigrant parents

U.S. children whose parents are deported often struggle with school, finances, friendships

An estimated 5,100 U.S. kids in 22 states have had parents detained or deported, say experts

They came home from school to find their father missing.

It had started off like any other day. As usual, Ronald Soza dropped off his kids Cesia, 17, and Ronald Jr., 14, at school in Pompano Beach, Florida.

Ronald Soza returned home to find U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents waiting for him at his doorstep. Soza, an undocumented immigrant from Nicaragua, was taken to a detention center.

When the teens – both legal residents – came home to an empty house at the end of the day, they realized something was very wrong.

Then the phone rang. It was their father, trying to reassure them that everything would be OK.

“Even though we knew my father might get deported, we never thought that it would actually happen, especially since ICE already took our mother away five years ago” Cesia told CNN.

But it did happen. Ronald Soza was deported to Nicaragua, joining his wife, Marisela.

Suddenly, the teens’ parents were gone and the Soza children faced a frightening future with foster families and unfamiliar schools.

It’s been weeks since that terrible day last September, and they still haven’t seen either of their parents.

The Soza kids “were devastated after their mother was deported,” said Nora Sandigo, a family friend and immigrant rights activist. Now, they’re “living a tragedy … they’ve lost everything, their parents, home… everything.” Now they’re living with Sandigo and her husband and two girls in Miami.

How immigration reform would affect 3 families

ICE told CNN in a written statement that Soza was arrested last year and was allowed to return home under certain conditions, such as attending appointments with immigration authorities. But while under supervision, Soza committed 39 violations, including failure to attend appointments with immigration authorities, according to ICE.

Cesia said her father was overwhelmed with his single-dad duties. He did attend his ICE appointments, she said, although “it’s possible he arrived a few minutes late. But perhaps they counted that a no-show.”

The siblings represent America’s young legal residents who are at risk for long-term emotional trauma because of a system that doesn’t deal with the situation. About 5,100 U.S. children in 22 states have lost parents to deportation, according to the Applied Research Center – a 30-year-old racial justice think tank. Some 15,000 more face similar threat in the next five years.

These families live in constant fear of deportation as their kids attend school and pledge allegiance to the flag. Constantly worrying that their parents will be snatched away, children often feel angry, helpless and trapped.

Families like the Sozas are referred to by the system as “mixed-status families.” Ronald Jr. was born in the United States. Cesia – who was born in Nicaragua –lives in the U.S. legally under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program. DACA grants two-year reprieves from deportation to undocumented youths who came to the U.S. as children.

At their father’s request, Sandigo has become the Sozas’ legal guardian. She receives no government funds to offset the cost of raising them.

Making ends meet isn’t easy. The Soza teens rely on whatever their parents can send from Nicaragua. It’s not much. Their father – who works in construction – says he has had a difficult time finding a job since moving there.

“We’ve had to leave everyone we knew behind, switch schools, and we’re constantly trying to catch up in our new school,” said Cesia. In the middle of all the chaos, she’s been juggling paperwork for her immigration status while filing applications to several universities. Another problem: being under Sandigo’s guardianship may threaten Cesia’s ability to qualify for college financial aid.

“It’s been really stressful doing all this without my parents,” she said. “I miss them so much.”

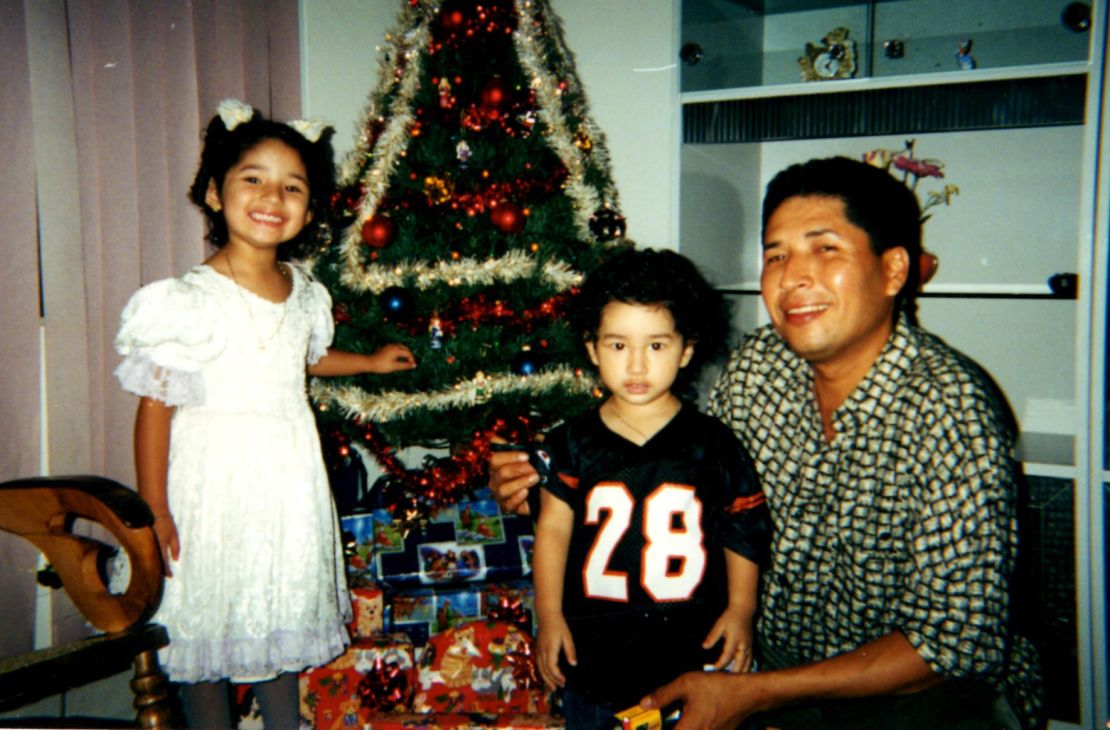

But the siblings have managed to hold on to a few reminders of their former life: some family photos and their precious Chinese Shar-Pei, Snoopy. They talk to their parents on the phone every day. Cesia says it doesn’t come close to having them by her side.

Anguishing decision

Their behavior has changed since that day in September, Sandigo said. At school, the teens keep to themselves and don’t talk much with other kids. Sandigo worries they may be depressed and are withdrawing from social interaction.

Experts say repercussions of traumatic experiences like the Sozas’ can take a serious toll.

“The psychological effects on these children left behind include depression, possible conduct disorders, and having a constant sense of a diminishing and ambiguous future,” said Dr. Luis H. Zayas, dean of the School of Social Work at the University of Texas. “No parent should be put through such an anguishing decision of whether or not to leave a child behind, but most importantly, how will these kids feel about their government when they grow up?”

An estimated 340,000 babies born in the United States in 2008 were the children of unauthorized immigrants, according to the Pew Hispanic Center. That number is projected to grow.

On average, 17 children are placed in state care each day as a result of the detention and removal of immigrant parents, according to ICE.

Some kids are fortunate enough to have other family to stay with, said Zayas. Others get lost in the child welfare system. In some cases, younger children are transferred to state custody and put up for adoption, never to see their parents again.

In the end, Zayas warns that the policy threatens to hurt the nation in the long run.“What other future does the U.S. have other than losing a whole generation of kids because of the way their parents were treated?”

Torn between two nations

Desperate to reunite with their parents, Cesia and Robert Jr. have considered moving to Nicaragua – an idea opposed by their father, who believes there’s no future for them there. The parents left Nicaragua in the 1980s because the government, they said, was putting too much emphasis on political indoctrination and social control.

But the teens’ argument about why they should stay in the U.S. is this: They feel they are Americans. The United States is their home.

“I came here when I was 18 months old and I don’t know Nicaragua at all,” Cesia said. Ronald Jr. admitted his Spanish is less than perfect. “I can contribute more here than in Nicaragua,” he said.

Sandigo wishes she could do more to help. “But I can’t replace their parents,” she said.

She accuses the Obama administration of failing to honor its pledge to make parents like the Sozas less likely to be deported.

The Obama administration stated in 2012 that undocumented immigrants without criminal records would be considered low-priority removals, including those parents of U.S.-born children with strong ties in the United States.

Sandigo argues that if this were the case, Cesia and Ronald Jr. would be with their parents today.

Overall, Sandigo questions whether federal officials are committed to making sure children whose parents are deported are properly taken care of.

“I have yet to receive a call from ICE asking if these children are even alive – yet with a legal guardian,” she said.

It’s almost impossible to know the full scope of the problem. Child welfare departments and the federal government aren’t required to track cases of families separated by deportation.

During the past 25 years, Sandigo says she has found homes for about 800 children whose parents have been detained or deported.

On Capitol Hill, lawmakers seem to give little attention to the situation. Some say a bipartisan immigration reform bill passed by Senate in 2012 might help. Supporters say it aims to provide a path to citizenship for the nation’s estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants, strengthen border security and change the visa system.

Opponents in the House, many of them Republicans, reject any reform that involves what they consider “amnesty” for undocumented immigrants.

In Florida, the Soza children long to see their parents again. And they haven’t given up.

“Although we are separated, we are still united in a way,” said Cesia. “I have to stay hopeful that this will all work out.”