Editor’s Note: John Sides of George Washington University, and Lynn Vavreck of UCLA are political scientists and the authors of the new book “The Gamble: Choice and Chance in the 2012 Election”.

Story highlights

Authors: Some midterm elections are like tidal waves that remix the Washington scene

Democrats had their wave in 2006, Republicans in 2010, they say

But radical change in Washington from 2014 election may not happen, they say

Authors: Government shutdown isn't likely to change the outcome

A midterm election sometimes arrives like a tidal wave, sweeping one party’s incumbents out of office and bringing in a new majority. For Democrats, their wave came in 2006. For Republicans, theirs came in 2010.

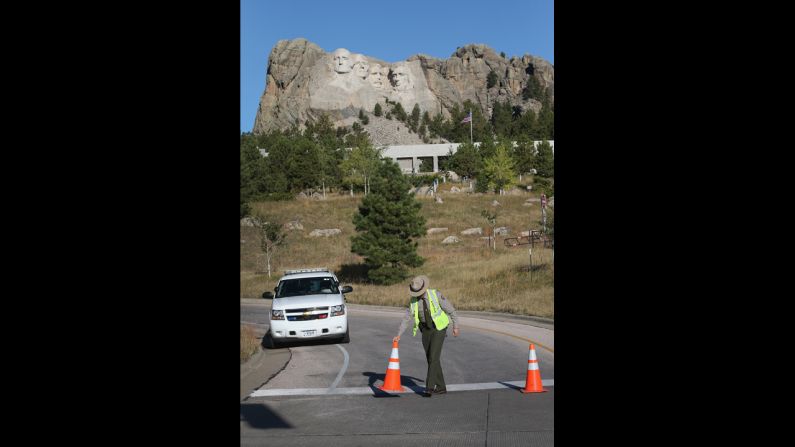

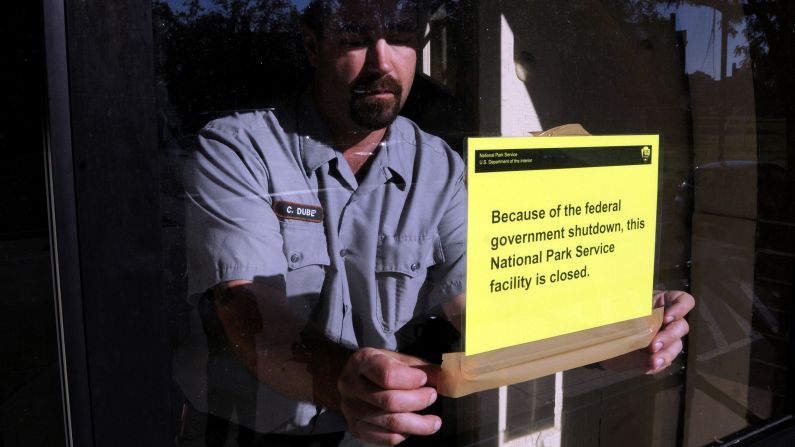

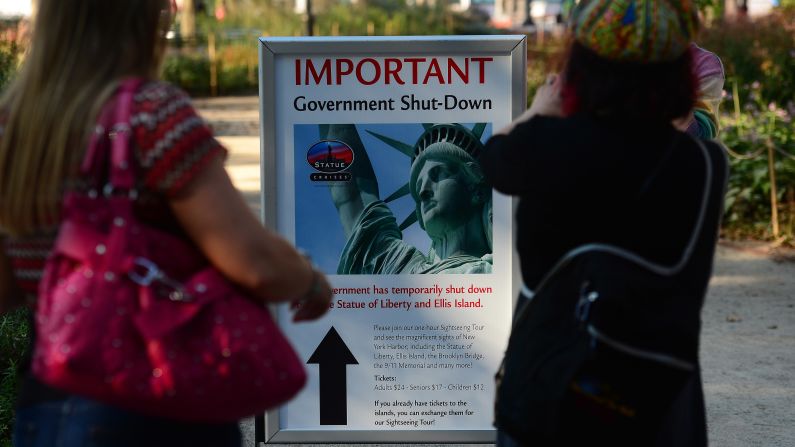

As the next midterm election approaches, however, there are few signs of a tsunami. 2014 seems likely to reproduce divided government and, with it, even more of the partisan polarization that has become endemic in American politics. Thus, the next election seems unlikely to change the dynamics that have produced the partial government shutdown.

Loyalty to a political party is not just a feature of Congress. It is, and has always been, a pre-eminent force in American elections. Nine in 10 Americans identify with or lean toward a party, and most vote loyally for that party. In our book, “The Gamble,” we document the powerful role partisanship played in the 2012 election.

In partnership with YouGov, we interviewed 45,000 Americans online in December 2011 and then interviewed most of them again after the election. Of those voters who described themselves as Republicans or Democrats that December, more than 90% voted for their party’s candidate.

Voters who were undecided in December also tended to vote in line with their underlying partisan loyalties. The same party loyalty has increasingly carried over into congressional elections as well. This is one reason why split-ticket voting has dropped so precipitously in the last 40 years.

Some maintain that the 2012 election inaugurated an “Obama realignment” or “Liberal America.” As we argue in “The Gamble,” it was always unlikely that the election signaled Democratic or liberal ascendance. In reality, Obama won despite a sharp conservative turn in public opinion and despite being perceived as ideologically further from the average voter than Romney was. The election mainly signaled just how narrowly divided the country is.

Heading into 2014, a set of cross-currents seems likely to maintain this partisan balance. Republicans have more seats to defend in the House, and history shows that the larger a party’s majority, the more seats the party is likely to lose. On top of that, the dismal marks that Americans give to Congress tend to hurt the majority party in the House most.

But the Democrats face their own challenges. Two key fundamentals in both presidential and midterm elections are the economy and presidential approval. At the moment, the economy is growing only slowly, and approval of Obama has dropped 8 points since January. Both factors could end up hurting congressional Democrats. Moreover, in the Senate the Democrats must try to hold seats in Republican-leaning states like Alaska, Arkansas, Montana, New Hampshire and Louisiana.

When you put these factors together, Republicans are currently forecast to gain a small number of seats in both chambers, although this could be enough to give them a narrow majority in the Senate.

Is the shutdown likely to change this dynamic and strengthen Obama’s hand against Republicans? Probably not. Although the last big shutdown battle in 1995-96 did no favors for Newt Gingrich and House Republicans, it did not necessarily help Clinton in the eyes of voters—contrary to the conventional wisdom today. Clinton’s approval was no higher immediately after the two shutdowns than before, and it is unclear whether the increase in his approval later in 1996 stemmed from the shutdown itself.

Moreover, this time Americans seem willing to spread the blame for the shutdown. They are only slightly less likely to say they will blame Obama and the Democrats than blame Republicans. Indeed, during the last big debt ceiling fight with the GOP—in summer 2011—Obama’s approval rating dropped 5 points.

None of this is to say that the shutdown can’t damage Republicans, too. If the conservative faction of the party continues to drive policy, the dwindling, but vital, number of Republican moderates may find themselves electorally vulnerable. Political science research shows that being more ideologically extreme or partisan than their district can hurt members of Congress at the ballot box. John Boehner has to find a way to protect moderates—some of whom are clearly chafing–and placate conservatives at the same time.

Ultimately, the 2014 election seems likely to give us more of the slow grind of divided government. This will continue to hamstring both parties and frustrate Americans ready for an end to gridlock.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the authors.