Story highlights

The spacecraft had completed its initial mission and had been used for others

Its data and images helped confirm the existence of water on the moon

It yielded key information about the composition of comets

The most-traveled comet-hunter mission in history has ended, NASA announced with reluctance Friday as it shut the book on the Deep Impact spacecraft.

“It has revolutionized our understanding of comets and their activity,” said Mike A’Hearn, the mission’s principal investigator at the University of Maryland in College Park.

In its nearly nine years in space, the spacecraft “has produced far more data than we had planned,” including half a million images of celestial objects, A’Hearn said in a news release.

The decision to declare the mission complete was made by the project team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, after it lost communication with the spacecraft after August 8 and could not re-establish it.

By then, it had traveled across 4.7 billion miles of space.

“It was scheduled to talk to us on August 14 and never showed up,” said Timothy Larson, project manager and deputy director for safety and success at JPL.

Engineers believe the problem was caused by a software bug. After trying without success to re-establish contact, they declared the mission officially over on September 17, and the spacecraft is now orbiting the sun as space junk.

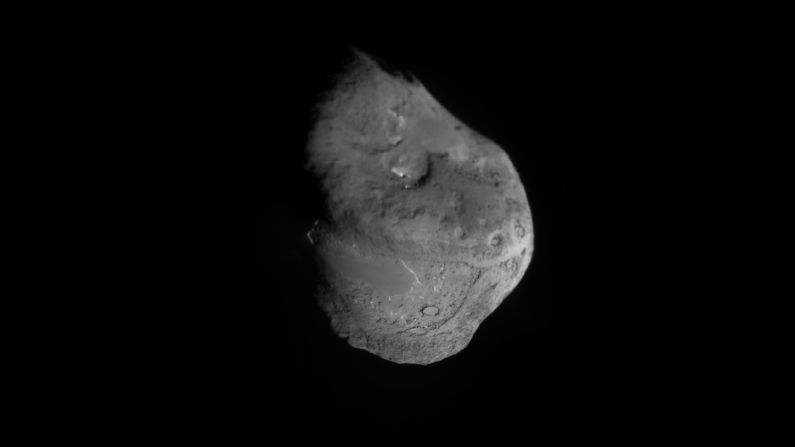

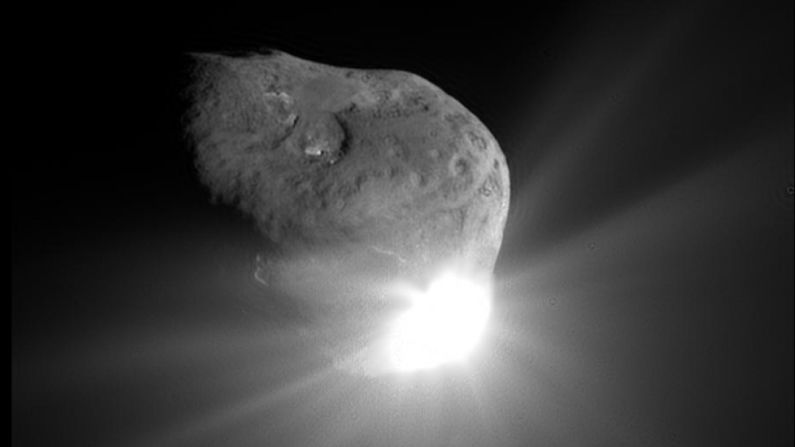

Its abrupt end as a tool of science came years after that end had originally been envisioned. The initial mission was launched in 2005. Within six months, it had positioned an impactor into the path of a comet, dubbed Tempel 1, and then observed what happened when the two objects collided.

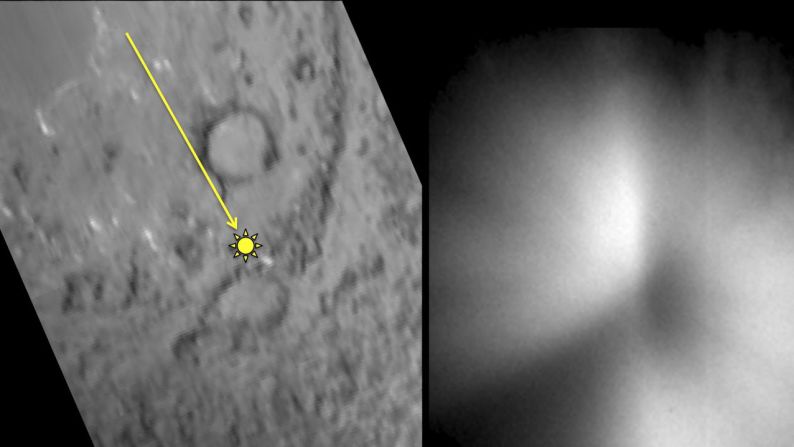

“What was surprising was to find out how loosely packed the material is, how porous it is,” Larson said. “We were also able to determine that material’s chemical composition is pretty much the same down to 10-20 meters below the surface.”

Though the $333 million Deep Impact project was complete and deemed a success, NASA engineers – noting that the spacecraft still contained fuel – decided to try to extend its life to include a second study, which was carried out in 2010 looking at a comet called Hartley 2.

That mission – which cost just $39 million because it did not need a new spacecraft – also yielded useful data, but depleted most of the fuel supply. So, Deep Impact was then used as a platform – left in orbit around the sun – from which to study space.

All of those involved will go on to other projects, Larson predicted. But the project, though ended, will leave a legacy, he said: “It gave us surprising new insights into what comets are made of, how they’re formed, where in the solar system they might have been formed and how they behave as they come in close toward the sun.”

Among those accomplishments was taking images and data of the moon that helped confirm the existence of water there.

Over the years, the team involved in the project has dwindled – from 130 in 2005 to about 20 or 30 in 2010 and, for the past couple of years, four or five, Larson said.

Those remaining plan to get together to mark the ending of Deep Impact. “I don’t know if we’ll call it a party, but we’ll definitely celebrate all the accomplishments that we’ve had with this one,” Larson said. “It did a lot more than originally intended. It will be a sad good-bye.”