Story highlights

30 years ago this weekend, the Soviet Union shocked the world by shooting down a 747 airliner

Korean Air Lines Flight 007 strayed over Soviet territory; 269 passengers and crew died

Cold War tensions in 1983 fueled Soviet suspicions the 747 was spying

The tragedy spurred a movement of victims' family activist groups

The idea that Soviet fighter jets would shoot down a Boeing 747 airliner seems shockingly unbelievable. Two-hundred sixty-nine innocent people died in a largely forgotten Cold War attack that took place exactly 30 years ago this weekend.

On a sultry August night in 1983 at New York’s JFK airport, Alice Ephraimson-Abt, a brilliant, 23-year-old blue-eyed blonde, was about to board Korean Air Lines Flight 007 for Seoul, South Korea, halfway around the world. For one last time, she held her father, New Jersey businessman Hans Ephraimson-Abt, before saying goodbye. “There were hugs and I-love-yous,” her father, now 91, told CNN.

Alice – who was excited about heading Beijing to teach English and study – could have been a diplomat, a contributor to peace, her father said. “Her death was a great loss to her generation.”

The ramifications of the shoot-down of Flight 007 reverberated far beyond the lives lost. It sparked global outrage, conspiracy theories and an activist movement that continues today. It also joined a list of disturbing developments that made 1983 one of the scariest years of the Cold War. Not since 1962’s Cuban Missile Crisis had the world teetered so close to the unthinkable, according to declassified documents released in May.

It seemed like each month brought with it new and troubling headlines.

President Ronald Reagan, in March, said the Soviet Union amounted to an “evil empire.” A few weeks later, Washington announced that it was working on a new space-based weapon. The press dubbed it “Star Wars.”

That October, on the Caribbean island of Grenada, a coup and the deployment of pro-Soviet Cuban forces prompted the Pentagon to invade with thousands of troops. The following month, the United States and NATO staged war games that depicted a nuclear attack scenario.

Fear seeped into TV, movies and music. In November, more than 100 million viewers tuned into ABC’s nuclear attack drama “The Day After.” The following month, film crews began shooting “Red Dawn,” about a Soviet invasion of America. Playlists on radio and MTV included “99 Luftballoons,” a Cold War protest song.

But it was the downing of KAL 007 that opened many eyes to the Cold War’s widening wave of darkness, its increasing uncertainty and its growing threat to peace.

Alice Ephraimson-Abt’s flight made a refueling stop in Anchorage, Alaska, and – following the tradition of the well-traveled family – she phoned her father. She told him about a U.S. congressman, Rep. Larry McDonald, who also was aboard. One of 61 Americans on the plane, McDonald was a conservative Georgia Democrat and outspoken anti-communist.

What we know about the next five hours aboard Flight 007 comes from CNN interviews with ex-Soviet officials, the cockpit voice transcript and a 1993 report from the United Nations’ International Civil Aviation Organization.

After the 747 took off for Seoul at 4 a.m. local time, the crew set their autopilot. What they apparently didn’t know was, it was set to fail.

The plane began drifting off its intended course and heading toward Soviet territory.

Hours later, passengers heard the familiar crew announcement, “Good morning ladies and gentlemen, we will be landing at Seoul Gimpo International Airport in about three hours. Local time in Seoul right now is 3 a.m. Before landing, we will be serving beverages and breakfast, thank you.”

But sadly, there would be no landing.

Twenty-six minutes later, the captain was announcing an emergency descent and ordering crew to put on oxygen masks.

Fighter pilot:‘I had a job to do’

As it neared Soviet airspace, Flight 007 was being tracked at military installations. Soviet fighter pilots and their commanders knew they were being watched, too. U.S. spy planes patrolling the region created a constant state of tension, they said later.

American surveillance aircraft included Boeing RC-135s, the military version of a Boeing 707, which looked very much like a civilian airliner.

Packed with electronic surveillance gear, RC-135s often flew figure-eight patterns near passenger routes.

By this time, Flight 007 had deviated more than 200 miles from its planned route.

Commanders at Dolinsk-Sokol airbase scrambled two Sukhoi Su-15 fighter jets and ordered them to intercept the airliner.

“I could see two rows of windows, which were lit up,” Soviet pilot Col. Gennadi Osipovitch told CNN in 1998, describing the 747’s telltale double-deck configuration. “I wondered if it was a civilian aircraft. Military cargo planes don’t have such windows.”

“I wondered what kind of plane it was, but I had no time to think,” Osipovitch recalled. “I had a job to do. I started to signal to (the pilot) in international code. I informed him that he had violated our airspace. He did not respond.”

The Soviets fired warning shots with brightly lit tracers, said Soviet Lt. Gen. Valentin Varennikov.

Inside KAL 007’s cockpit, the flight crew appeared to be unaware of the Soviet fighters flying alongside. The pilot failed to react, the general said, and continued on course.

No attempt was made to contact the airliner via radio. The Soviet pilots failed to follow “ICAO standards and recommended practices related to the interception of civil aircraft,” the International Civil Aviation Organization report said.

Soviet command gave Osipovitch his instructions. “My orders were to destroy the intruder,” Osipovitch remembered. “I fulfilled my mission.”

When news of the shoot-down reached Washington and Moscow, both reacted with outrage.

Reagan called the attack a “massacre” and a “crime against humanity” with “absolutely no justification, legal or moral.”

Soviet leader Yuri Andropov accused Washington of a despicable setup: a “sophisticated provocation masterminded by the U.S. special services with the use of a South Korean plane.”

Over the following months, Moscow cast a shroud of secrecy over the crash site off Sakahlin Island, never revealing whether it had found the plane’s wreckage, flight data recorders, survivors or bodies. Victims’ families were forced to grieve without burying their loved ones.

Unwilling to surrender, a handful of family members formed an advocacy group, the first of its kind. Alice Ephraimson-Abt’s father was among them.

As a kind of living memorial to Flight 007, Hans Ephraimson-Abt and his colleagues formed the American Association for Families of KAL 007 Victims, which pushed and worked with government bureaucrats around the world to learn all the details surrounding the disaster – with limited success.

Then, something amazing happened: The Cold War ended.

Somehow, the world had made it through.

The breakup of the Soviet Union opened doors to KAL 007’s data.

In 1992, during a top-level meeting in Moscow, Russia finally released the cockpit voice recorder transcript. It was 10 p.m. in a dimly lit meeting room of the Presidential Hotel when an interpreter for the U.S. ambassador translated the Russian transcript into English for Ephraimson-Abt and other delegates.

For the first time, Alice’s father would know how his daughter and the 268 others had perished.

Slowly – word by word – he learned a terrible truth: The plane wasn’t destroyed in the air.

Missile fragments “hit the back of the plane, destroying three of its four hydraulic systems, severing some cables” and punching holes in the aircraft’s walls, said Ephraimson-Apt, citing a Boeing report to the International Civil Aviation Organization. “No perceptible cabin pressure was lost, and all four engines continued to operate.”

The damaged plane continued flying for 12 minutes, spiraling toward the ocean below, until it “crashed into the sea, with most passengers smashed into pieces or drowning,” Ephraimson-Apt said.

“That was, emotionally, a rather hard thing to take.”

Questions breed suspicion

Thirty years later, almost all the important questions surrounding the crash have been answered, said Ephraimson-Abt. “What is not resolved is what happened to the bodies of our loved ones. The Russians to this day claim they haven’t recovered any bodies.”

So what happened to the bodies?

That simple question triggers intense debate among Flight 007 conspiracy theorists. Some believe the lack of bodies indicates that the Soviets somehow rescued Rep. McDonald and other passengers – and then imprisoned them for years. That’s the theory explored in the 2001 book “Rescue 007,” by Bert Schlossberg, a son-in-law of one of the victims. The book cites witnesses who reported seeing passengers housed in Siberian prisons.

“A lot of people wanted to believe that, for their loved ones, but I don’t think there’s any veracity to it,” said attorney Juanita Madole, who represented 100 Flight 007 victims and their families for decades.

Another theory said the Soviets intentionally destroyed any bodies they found because they wanted to hide evidence of the incident. “That’s just speculation,” Madole said. “People like to speculate. It makes it more intriguing.”

The whereabouts of the bodies of Flight 007 stands as a Cold War mystery that may never be entirely solved.

Pilot error

Overall, the International Civil Aviation Organization said pilot error contributed to the disaster, despite the fact that the crew brought respectable experience to the flight.KAL 007 pilot Chun Byung In reportedly had logged 11 years operating civilian airliners. Before that, he’d reportedly served as a stunt pilot in South Korea’s air force.

Author Asaf Degani, a former NASA expert on cockpit information systems, says KAL 007’s autopilot was probably in “heading” mode. That setting tells the plane to follow a course according to the magnetic compass, which can vary in accuracy up to 15 degrees at high latitudes.

It was this autopilot mode that is believed to have put the plane into Soviet airspace. If the autopilot had been flying under the plane’s highly accurate, computerized “INS” (inertial navigation system) setting, the 747 would have flown a different path, keeping it very close to – but still out of – Soviet airspace. The pilots, Degani suspects, may have mistakenly thought they were flying in INS mode.

“Chances are much less that this kind of confusion would happen now,” Degani said, “because, by the turn of the century, most commercial airliners flying intercontinental routes had display systems that show which autopilot mode – ‘heading’ or ‘INS’ – is actually flying the airplane.

“Unfortunately,” said Degani, “These design changes came too late to help the crew and passengers of Flight 007.”

Tensions rise and fall

International military tensions have continued to rise and fall since 1983, putting civilian airline passengers at various levels of risk.

In the volatile Persian Gulf, just five years after Flight 007, the USS Vincennes shot down an Iran Air Airbus A300 flying from Teheran to Dubai. The Navy mistakenly ID’d the airliner as an attacking fighter jet and fired on it, killing all 290 passengers and crew.

And although the Cold War is long over, tiffs between Washington and Moscow continue, even in 2013. “I think there’s always been some tension in the U.S.-Russian relationship after the fall of the Soviet Union,” Obama said August 9. “There’s been cooperation in some areas; there’s been competition in others.”

Obama hits pause button with Russia

As for Hans Ephraimson-Abt, he and fellow family members have helped other families, nations and airlines form advocacy and support organizations after some of the worst plane crashes of the past 30 years.In 2000, many of these organizations around the world united under the international Air Crash Victims Families Group, which enjoys invited “observer” status at the International Civil Aviation Organization and stakeholder status at the European Union. And it all began as a handful of family members supporting each other during one of the scariest periods of the Nuclear Age.

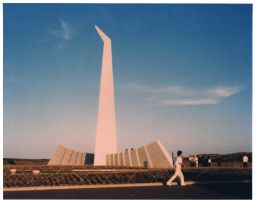

Permanent memorials for KAL 007 include a small cemetery marker on Russia’s Sakahlin Island and a 90-foot tower in Wakkanai, Japan, where some remains and personal effects that washed ashore in 1983 are kept. The tower consists of 269 white stones and two black marble slabs inscribed with the names of passengers and crew.

Memorial services at Wakkanai will mark this weekend’s anniversary. But Ephraimson-Abt won’t be there.

Instead, he expects to remain at home in Ridgewood, chatting by phone with fellow KAL 007 family members who’ve supported each other through the years.

“We all know what we remember, so not many words have to be said,” he acknowledged. “We’re beyond consoling each other. But we never forget that each year there is a date when we particularly remember our loved ones.”