Story highlights

There are approximately 1,100,000 teens playing high school football

Confusion, nausea, headache are some of the symptoms of concussions

NFL players receive an estimated 900 to 1,500 blows to the head each season

High schools are changing the rules and implementing safety programs

Jason Stevens remembers all too well the feeling of not being sure where he was. He suffered a concussion during the third game of his high school football season last year, and had to sit out for the rest of the season.

“It felt like the entire helmet was just pressing in your head, like your head was expanding,” said Jason, 15, of Poughkeepsie, New York.

Football teams across the country are getting the message: It’s time to tackle concussions.

In a landmark move Thursday, thousands of former football players and their families reached a settlement with the National Football League. According to court documents, the NFL will pay $765 million to fund medical exams, concussion-related compensation, medical research for retired NFL players and their families, and litigation expenses.

It’s an issue for more than the nation’s top football players. There are approximately 1,100,000 teens playing high school football, according to The National Federation of State High School Associations. And in organized youth leagues, there are another 3 million.

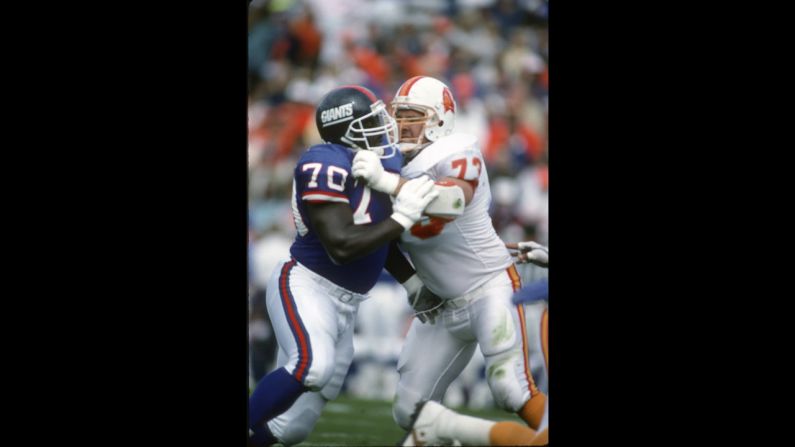

Concussions result from blows to the head, such as when a player collides with another in a sporting event.

“In a football game, when someone takes a hard hit, the helmet does a pretty good job of protecting the skull from getting a skull fracture,” Dr. Sanjay Gupta, a neurosurgeon and CNN’s chief medical correspondent, told Bleacher Report. “But what is really happening when someone is running down the field and … they get hit – the brain keeps moving inside the skull.”

It’s not so much the hit, although that’s important, but the sudden acceleration and deceleration of the brain that causes the concussion, Gupta said.

Confusion, nausea, headache and loss of consciousness are some of the immediate symptoms of concussions, but they can also have longer lasting effects. Severe impacts to the head can lead to bleeding or permanent nerve damage. And recent research has shown that repeated hits to the head can lead to a brain disease known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE.

In the 2012 football season, there were two fatalities directly related to football, both in semi-professional football, and both during regularly scheduled games, according to the Annual Survey of Football Injury Research [PDF].

“In 2012, one of the semi-professional players was hit by a blindsided block on a punt return and the second player was involved in a helmet-to-helmet collision,” the report said.

Among high school football athletes, there were nine indirect fatalities – one from heat stroke, four related to the heart, two from asthma, one from lighting, and one of an unknown cause. None were impact-related, but earlier this month a teen in Georgia died after he broke his neck while making a tackle during a scrimmage game.

Over the last 10 years, an average of fewer than three boys a year have died from on-field injuries playing high school football, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research at the University of North Carolina. More concerning to experts is the repeated hits they’re sustaining on the field.

A professional football player receives an estimated 900 to 1,500 blows to the head during a single season, according to the Sports Concussion Institute in Los Angeles. How many is that over a lifetime?

The NFL has initiated strict sideline concussion rules and cognitive tests, to be administered by trainers and doctors who cannot be overruled by coaching staffs. But changes are happening on lower levels as well.

The National Federation of State High School Associations Football rules committee approved rule changes earlier this year regarding what should happen when players’ helmets come off of their heads during games.

To minimize risks, these rules included an illegal personal contact foul mandate: “No player or nonplayer shall initiate contact with an opposing player whose helmet has come completely off.”

Also, it will be illegal “for a player whose helmet comes completely off during a down to continue to participate beyond the immediate action in which the player is engaged.”

Any player whose helmet comes off during the game is also forced to sit out at least one play.

The National Federation of State High School Associations announced earlier this month that it has partnered with USA football to endorse a program that promotes high school football player safety.

The program is called Heads Up Football, and it currently involves 32 high schools in eight states. In 2014, any high school in the country will be able to participate.

High school programs that participate each assign a Player Safety Coach, who is trained by USA Football to instruct coaches, parents and players on specific tackling mechanics. The techniques are aimed at reducing helmet contact, concussion recognition and response protocols, and ensure adequate fitting for helmets and shoulder pads.

Heads Up Football will incorporate about 4,000 high school student athletes this year, as well as youth football programs that represent nearly 600,000 youth players in all 50 states and Washington.

A lot of schools in the Los Angeles area are requiring pre-season cognitive testing for football players, so that if a player gets a concussion, he can be re-tested and the results can be compared to the original screening, said Sidney Jones, athlete trainer and clinical coordinator at the Sports Concussion Institute.

Jones conducts education, pre-injury and post-injury testing throughout the Los Angeles area.

“I think as different things are happening – whether it’s NFL lawsuits, or more media attention on things like concussions – I think a lot more parents and schools are willing to try to protect their kids a little bit more, and get more education,” she said.

Jones has found that many student athletes – she mainly works with children 18 and under – do not know the risks of concussions. She educates them about prevention and symptoms.

She keeps it basic and does not talk about the long-term risks of concussions that have been getting a lot of attention in research. That’s because, in her view, “We don’t have the research available to us yet to actually concretely say anything.”

Some parents are taking matters into their own hands. Jason’s mother, Erika Stevens, wasn’t satisfied with the normal training on her son’s team, so she hired a personal trainer to help him avoid concussions in the future. He’s learned how to properly hit, and when to let the play go, over the past couple of months, she said.

“We hope that it makes him a smarter player.”

Jason said his team passed out new football helmets this season that are designed to minimize the risk of concussion more than old ones this season. He got one because of his injury last year.

Jason suffered attention problems in school for months after his concussion, and sat closer to the front of the class than normal because of eyesight difficulties, his mother said.

Training for this season – his first since the injury – began August 19.

His mother is nervous about him suffering another concussion, but Jason is not. Still, they’ve agreed: “If he does get another concussion, then football’s done,” Stevens said.

CNN’s Jacque Wilson and Stephanie Smith contributed to this report