Story highlights

Unrest in Syria started after children were arrested for anti-government graffiti

Outrage over arrests spiraled into protests that fueled an opposition movement

The White House has said chemical weapons are a game changer

Russia is standing by Syria, its longtime ally

The Pentagon says it’s “ready to go” if it gets orders to carry out a military strike in response to Syria’s suspected use of chemical weapons against its own people.

Most people know Syria’s civil war has been raging for more than two years. But the situation is so complicated that it’s hard for even the biggest news junkie to keep track.

Now that Washington is seriously thinking about ordering limited missile strikes in one of the most volatile regions of the world, it’s a good time to retrace events and remember how we got here.

Here’s a quick-read cheat sheet about the Syrian civil war. It’s not intended to be an all-encompassing encyclopedia, but it will bring you up to date on what’s really important about a scary situation in an already volatile part of the world.

Who wants what after chemical weapons horror?

1. What did Syria look like before the conflict?

Even before the uprising in Syria, things weren’t peaceful there. Discontent simmered for decades.

In 1982, President Hafez al-Assad clamped down on a Muslim Brotherhood uprising. In one attack, his iron fist left tens of thousands dead.

When Hafez al-Assad died in 2000, his son Bashar al-Assad took over the presidency. He promised to build a more modern and democratic nation.

But reforms didn’t come fast enough for activists, who called for change and slammed Syria’s government as an “authoritarian, totalitarian and cliquish regime.”

Sectarian and ethnic unrest shook Syria over the past decade, too. A Druze uprising flared in 2000, and a Kurdish rebellion erupted in 2004.

2. How did the civil war begin?

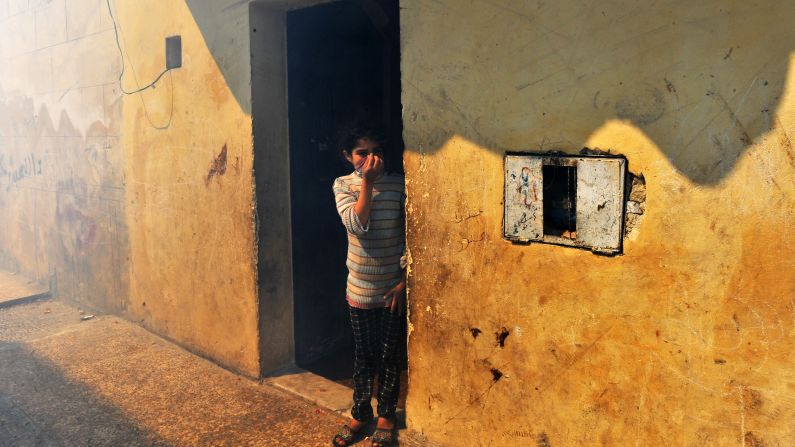

It all started in February 2011 in the city of Daraa, when authorities arrested 15 schoolchildren for painting anti-government graffiti on the walls of a school. The children didn’t mince words with the message they painted: “The people want to topple the regime.”

Word spread that the children were allegedly mistreated while in custody. Outrage over their arrest grew, fueling protests.

Security forces opened fire, activists say, killing at least four protesters.

These four, activists say, were the first deaths in Syria’s civil war.

Within days, according to Human Rights Watch, protests grew into massive rallies made up of thousands.

Their rallying cry: “Daraa!” the city whose children sparked a national movement.

Iran: U.S. military action in Syria would spark ‘disaster’

3. How did the unrest turn into a call for an end to al-Assad’s rule?

It didn’t take long for al-Assad to criticize protesters in Daraa. In a March 2011 speech before lawmakers, he said “conspirators” started out there and wanted to spread unrest.

His dismissive remarks, and the way lawmakers applauded afterward, only further fueled protests.

“That speech had a catastrophic impact,” the International Crisis Group’s Peter Harling said last year. “People who wanted to support the regime at the time were shocked.”

Two days later, weekly anti-government protests began across Syria. Calls for reforms soon escalated into calls for the removal of the entire al-Assad regime.

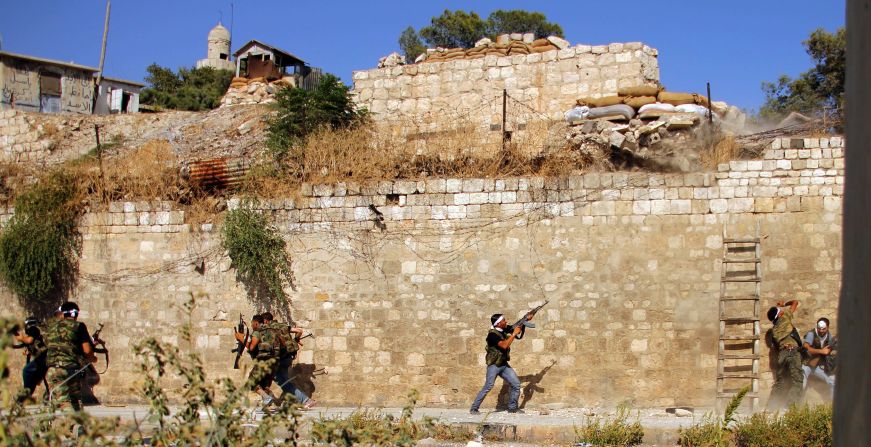

Now, armed rebels have vowed to accept nothing less than al-Assad’s ouster, while the Syrian government has labeled them terrorists and vowed not to back down.

The United Nations estimates that the fighting has claimed more than 100,000 lives.

4. OK, but that all started more than two years ago. Why do some people think the United States needs to take action now?

Talking about Syria last year, President Barack Obama said “a red line for us is, we start seeing a whole bunch of chemical weapons moving around or being utilized.”

The implication was clear. If Syria uses chemical weapons in the civil war, the United States will have to do something.

Now, the White House says it looks like Syria has used chemical weapons against its own people. So here we are.

What will Obama do in response? Whatever it is, it’s time to sit up and take notice, because this news story is moving to another level.

What justifies intervening if Syria uses chemical weapons?

5. What makes chemical weapons a game changer?

Some argue that conventional weapons like guns or bombs also have a massive human toll. They say chemical weapons shouldn’t be a turning point for the world to act.

But the White House maintains that they’re a game-changer.

“The use of chemical weapons is contrary to the standards adopted by the vast majority of nations and international efforts since World War I to eliminate the use of such weapons. … The use of these weapons on a mass scale and a threat of proliferation is a threat to our national interests and a concern to the entire world,” White House spokesman Jay Carney said this week.

6. Why didn’t the United States just send a bunch of weapons to the opposition when it had the chance?

In June, the United States said it would send the rebels small arms, ammunition and potentially anti-tank weapons. But that was long after the unrest started. Why the delay?

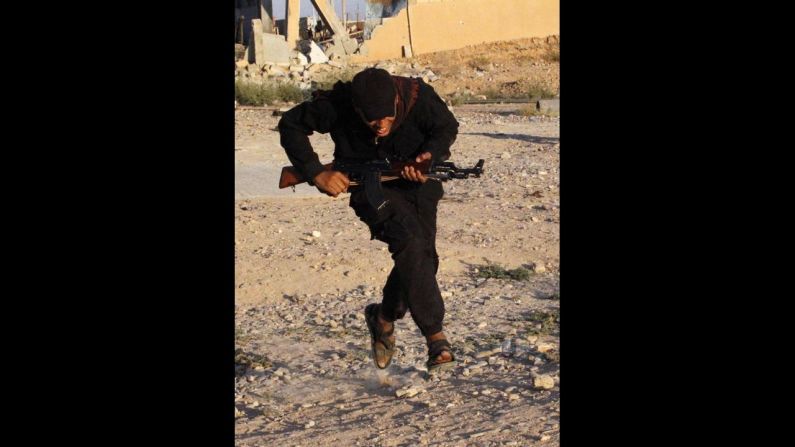

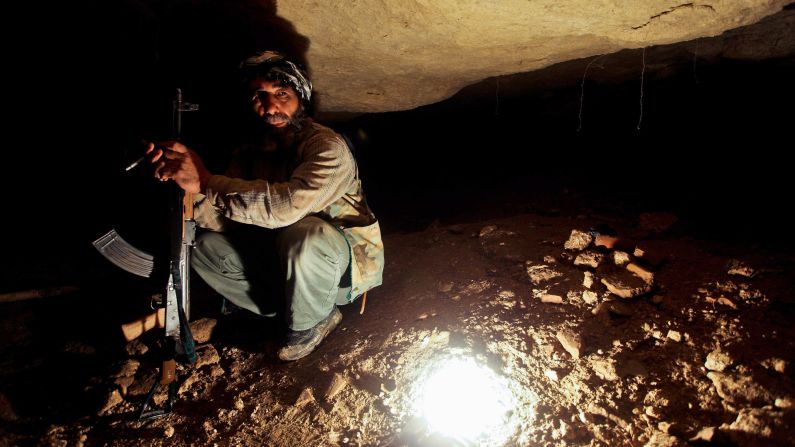

Some argue that sending weapons to a region of the world that also contains Islamic extremists is risky business.

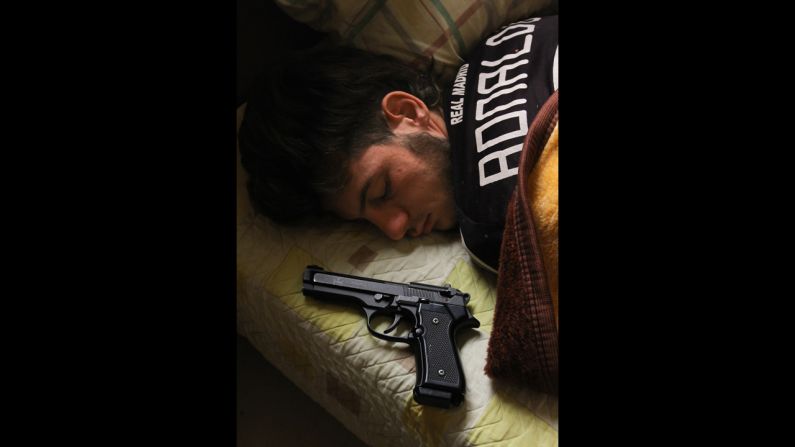

Many of the rebel fighters are militants with pro-al Qaeda sympathies, the same stripe of militants America has battled in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Syria rebels have promised U.S. and European officials that any military weaponry they get won’t end up in extremists’ hands. But that hasn’t quelled criticism from some quarters that arming the rebels is a dangerous risk.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has slammed the decision to arm the opposition. At an economic forum in June, he cautioned, “Where will those weapons end up?”

7. What’s the deal with Russia? Why are they criticizing the U.S.?

Putin has made it clear that Russia and the United States don’t see eye to eye when it comes to Syria.

Russia and Syria are longtime allies. For one, just take a look at their weapons deals. Between 2007 and 2010, Russian firms selling weapons to Syria made almost $5 billion.

It would be costly for Russia to end that relationship, analyst Peter Fragiskatos said this year

“Russia’s leadership still sees much to lose economically and strategically from cutting Syria loose,” Fragiskatos wrote. “Russia sees Syria as another test case for the West’s appetite for intervention and views the danger of U.S. involvement as a direct threat to its own interests.”

There are other reasons to suspect that Russia will keep supporting Syria. Russia’s only naval base in the Mediterranean is on the Syrian coast, and Putin is still upset about NATO’s bombing in Libya two years ago that removed Russian ally Moammar Gadhafi from power.

‘Red line’ debate: Chemical weapons worse than attacks?

8. What’s religion got to do with it?

The al-Assad family is Alawite, a Shiite Muslim offshoot that’s one of the minorities in a country that is nearly three-quarters Sunni.

Al-Assad has filled key positions in his government with extended family members, and many of his supporters are Alawites and other minorities who fear what might happen if the Sunnis were to gain power.

Because the Syrian regime is Alawite and the majority of the country is Sunni, there are concerns that Syria could spiral into even more violence.

9. What’s the worst that could happen?

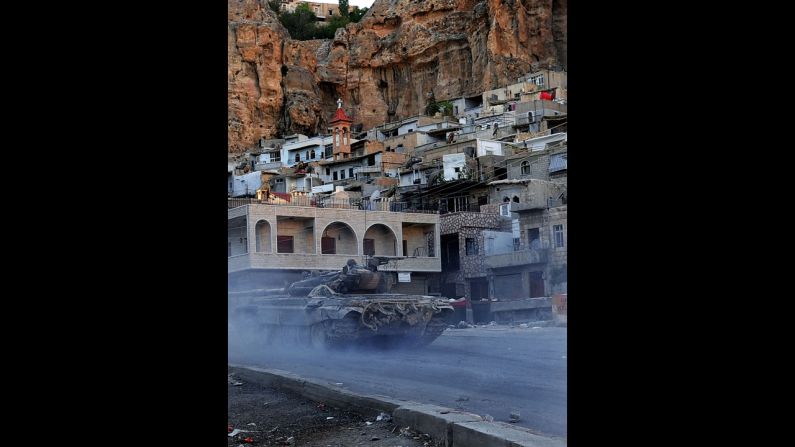

In a worst-case scenario, experts say, the fighting could spill over and make trouble for Syria’s neighbors, threatening stability in a part of the world that’s already known to be volatile.

Surrounding Syria are Lebanon, Iraq and Jordan, Israel and Turkey. The violence has been prompting war refugees to seek safety in some of these nations. In Turkey, there are ethnic tensions involving Kurds who live along its southern border with Syria.

All of these countries have a lot of religious, cultural and historical issues between them that add countless layers of complexity to the crisis. And when an entire region of the world loses stability, that worries the international community as a whole.

CNN’s Nic Robertson, Thom Patterson, Joe Sterling, Barbara Starr, Chelsea J. Carter and Kyle Almond contributed to this report.