Editor’s Note: Julian Zelizer is a professor of history and public affairs at Princeton University. He is the author of “Jimmy Carter” and “Governing America.”

Story highlights

Julian Zelizer: Americans bewail the failure of Congress to move on major issues

He says the March on Washington showed how citizen protest can result in change

Civil rights protesters were able to highlight injustice and to obtain remedies, he says

Zelizer: We should keep the march in mind when we think of today's Washington gridlock

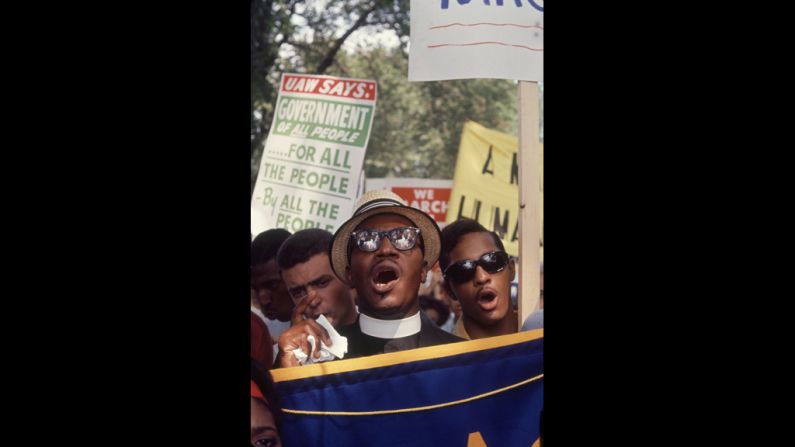

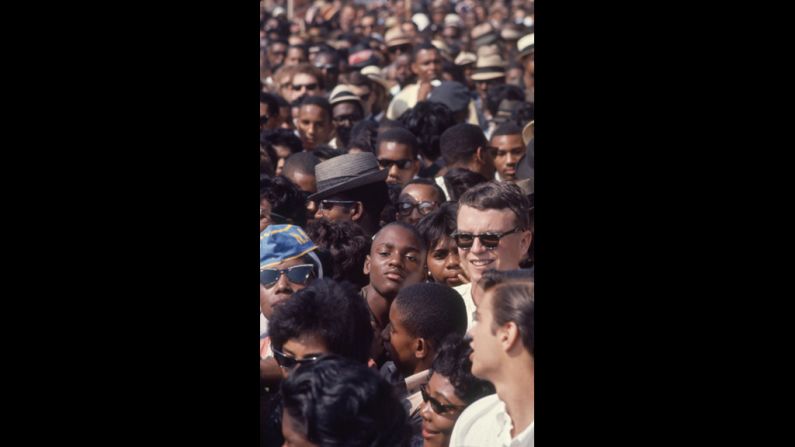

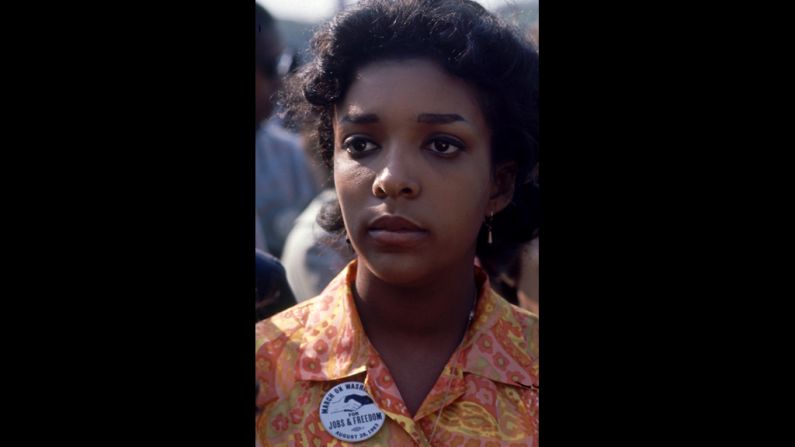

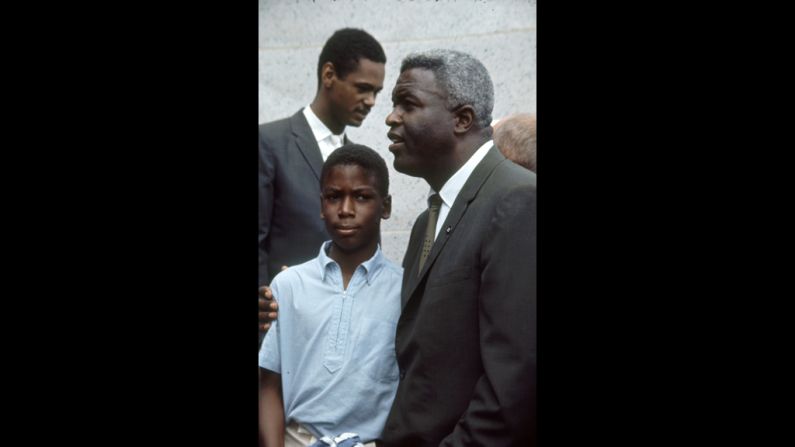

Fifty years ago this week, the civil rights movement rocked the nation’s capital. Bayard Rustin, Martin Luther King, Roy Wilkins and the other major civil rights leaders led thousands of activists in a march on Washington. Their goal was to build pressure on Congress to move forward with the civil rights bill that President Kennedy had proposed.

The march remains one of the most powerful examples of how social movements can affect political leaders and help break through the gridlock that often seizes Washington.

Although politicians and pundits constantly express nostalgia that things were easier in the past, the fact is that Congress has always been a notoriously difficult institution.

Where the problem today is that the parties are so polarized there is little room for agreement, in the early 1960s, the parties were so internally divided that bipartisan coalitions were able to stop legislative deals.

Brazile: We’re closer to the American dream

During the 1950s and early 1960s, an era when scholars and reporters complained about how little was accomplished on Capitol Hill, the main source of obstruction came from Southern Democrats and their conservative Republican allies. The “do-nothing Congress” was a familiar complaint then as it is now.

Southerners used their power as committee chairmen as well as the threat of the filibuster in the Senate to prevent action on civil rights and to ensure that any bill that did make it through — as occurred in 1957 and 1960 — was so watered down that it was ineffective.

Our lessons with Martin Luther King

Much to the chagrin of civil rights leaders, President Kennedy had shied away from proposing civil rights legislation during most of his term. He feared that sending a bill to Congress would hurt him in the 1964 election and cause Southerners to increase their opposition to his other domestic initiatives, like Medicare (in fact, Southerners ended up opposing civil rights and everything else, so Kennedy’s strategy did not work).

Civil rights activists responded by continually applying pressure on the White House to take action. Activists staged protests throughout the South, hoping that civil disobedience — and the violent responses of Southern authorities — would stimulate national outrage about racial conditions in Dixie. They were right. These efforts culminated in June 1963, when the police tactics of Sheriff Bull Connor and the Birmingham, Alabama, police force against African-Americans, including the use of fire hoses and police dogs against children, were so abhorrent that Kennedy could no longer hold back on proposing a bill. Indeed, liberal Republicans and Democrats were ready to move forward without the president.

50 years after King, hidden racism lives on

After Kennedy had finally sent a bill to the House, civil rights leaders rightfully didn’t have faith that Congress would move forward with it, or that Kennedy would work hard to make sure the bill did not die. They had seen a Congress that was so gridlocked on this and other issues, they didn’t have much reason to believe that this time things would be different. So ordinary citizens took it on themselves.

At the end of August, they conducted the massive March on Washington aimed at the nation but also at the legislators, who were impressed by the force of the protest. John Lewis, then one of the leaders of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, told those assembled on the National Mall: “By and large, American politics is dominated by politicians who build their careers on immoral compromises and ally themselves with open forms of political, economic and social exploitation…. Where is the political party that will make it unnecessary to march on Washington?”

Opinion: The anger, the fear, the love and the hope

The march was considered to be a stunning success, an act of civil protest that won public support for the cause and convinced a growing number of legislators to support the bill. Michigan Democrat Phil Hart, a liberal who originally did not think the march would do much, admitted that the “magnificent, moving, and edifying” protest had been effective.

The overall message was clear, one that leaders would continue to communicate over the next few months. If Congress tried to stifle the civil rights bill there would be more protests like this that embarrassed the nation in the eyes of the world, as well as protests in the states and districts of key legislators who were obstructing racial justice.

The civil rights bill would take some time to pass. The movement continued to put pressure on Congress, threatening even bigger marches and protests in their states if they did not act. The protests would continue throughout these months. In summer 1964, civil rights proponents finally brought the civil rights filibuster to an end and Congress passed legislation that ended desegregation in the South.

LZ Granderson: The man history erased

To be sure, other factors would play an important role in the success of the civil rights bill in the coming months. JFK’s assassination had created more political pressure on Congress to finish work on the bills that he had sent them. LBJ’s legislative skills helped the White House avoid the pitfalls of the legislative process.

But without the massive citizen mobilization that culminated with the March on Washington, the civil rights bill would never have succeeded.

The March on Washington, combined with the other grass-roots protests, was a shining example of how gridlock can be brought to an end and how average citizens can shake the political system when key actors are blocking progress on key issues of the day.

Today we should take a closer look at this march. In an age when certain members of Congress are unwilling to resolve so many issues — from gun control to immigration — it is worth remembering that in the past, citizens have been able to make a huge difference. Legislators are, after all, creatures of elections. If mass movements can make demands on the leadership and demonstrate the urgency of action, they might be the push legislators need toward the legislation that seems so elusive in 2013.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Julian Zelizer.