Editor’s Note: John D. Due Jr. is an attorney who has been a civil rights and community activist for more than five decades, primarily in the state of Florida but also in Mississippi, where he organized people to vote at risk to his life. In 1964, he represented the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. when King was arrested in St. Augustine. Due’s wife, Patricia Stephens Due, who led the first jail-in during the civil rights movement, died last year. CNN’s documentary “We Were There: The March on Washington - An Oral History” will be shown at 8 p.m. Sunday.

Story highlights

John and Patricia Due attended the 1963 March on Washington

For blacks, that summer was one of anger and fear, directed at JFK administration

Due: His wife was willing to stand up to authority, but she wasn't chosen to speak

He says the last speaker, Martin Luther King, found words to turn anger into love, hope

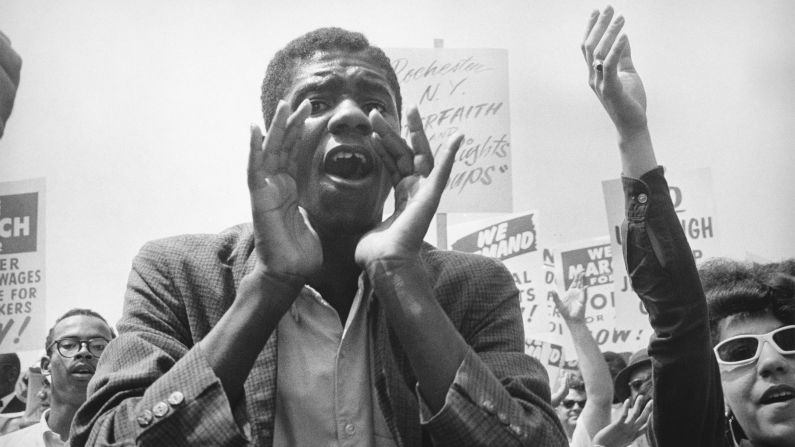

The summer of 1963 was hot. I’m not referring to the weather: Young black activists were beginning to question their commitment to nonviolent tactics.

Blacks were tired of feeling like their lives didn’t matter as government officials in the South watched, condoned, and/or led attacks against nonviolent demonstrators. Blacks were tired of the failure of the Kennedy administration to act. Blacks were tired of the reeking hypocrisy of the “New South” states like Florida, which tried to pretend that racial oppression didn’t exist within their borders.

My wife, Patricia, and I were at the March on Washington that hot summer.

She could have spoken that day. But they were afraid of what she would say.

Bernice King’s difficult journey

Florida’s tarnished image

Patricia had been arrested in May 1963 for demonstrating in front of a Tallahassee movie theater. She was a leader of the Tallahassee chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality, or CORE, an interracial group that used nonviolent tactics to fight discrimination, and had significant influence with the national organization. She was arrested with about 200 students mainly from a black college, the Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University, but also from white colleges Florida State University and the University of Florida.

Florida Gov. Thomas Leroy Collins had been nurturing an image of a new style Southern governor – one of moderation – to support tourism and investment in the planned Disney World attraction. Florida was supposed to be a “New South” state that was different from Alabama, with its police and Klan violence in Birmingham against youth in 1963, and neighboring states Georgia and Mississippi.

The case of Due v. Florida State Theater stemming from the students’ arrests was an embarrassment to the state, and was followed by demonstrations in St. Augustine with students from Florida Memorial College led by black dentist Dr. Robert Hayling, who was then the local National Association for the Advancement of Colored People youth adviser.

Florida’s “New South” image was tarnished after the Tallahassee and St. Augustine demonstrations, and the protests sabotaged the plans of Vice President Lyndon Johnson and the Kennedy administration, which had high hopes of having Miami Beach host the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

After the arrests of the college students in St. Augustine, I was in our apartment studying for the Florida Bar exam when Hayling called to ask Patricia for help. Could she use her influence with the national CORE to enlist their support in trying to block the Democratic National Convention from taking place in Miami Beach?

Naturally, she said yes. She called the national CORE office and sent a telegram to President Kennedy. She was not going to let Florida be portrayed as an idyllic paradise when she knew what blacks were experiencing there.

Full coverage of The March on Washington: 50th Anniversary

Rising anger among black youth

Patricia was not quite 24 in 1963, but she was well-respected by youth chapters of civil rights organizations throughout the state because of her leadership of the sit-ins in Tallahassee in 1960 and arrests and subsequent jail-in when she was only 20 years old.

Anger was growing among young student activists because of the violence police directed against them. After the St. Augustine demonstrations, Zev Aelony, a CORE field organizer, had gone to Ocala, Florida, to assist the new CORE chapter there. He was arrested and beaten in jail. When Patricia went to Ocala to try to visit Aelony in jail, she was arrested, along with the massive numbers of youth from the Youth Council of the Marion County NAACP who followed her there.

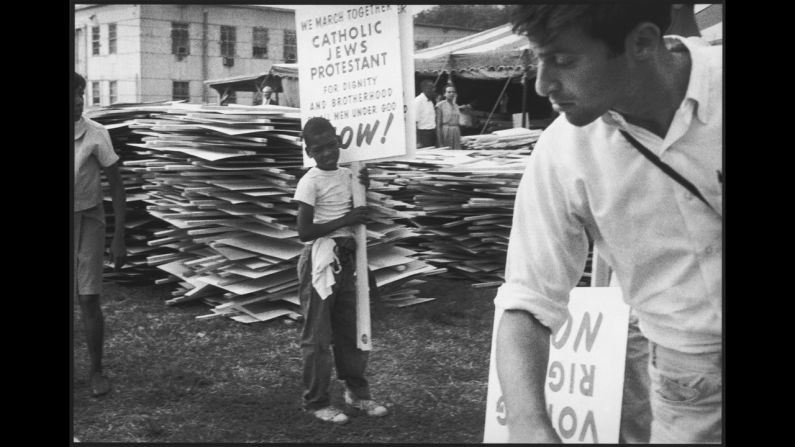

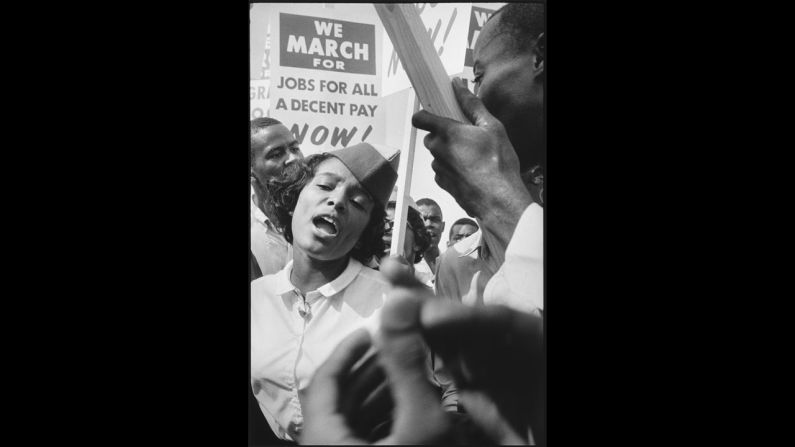

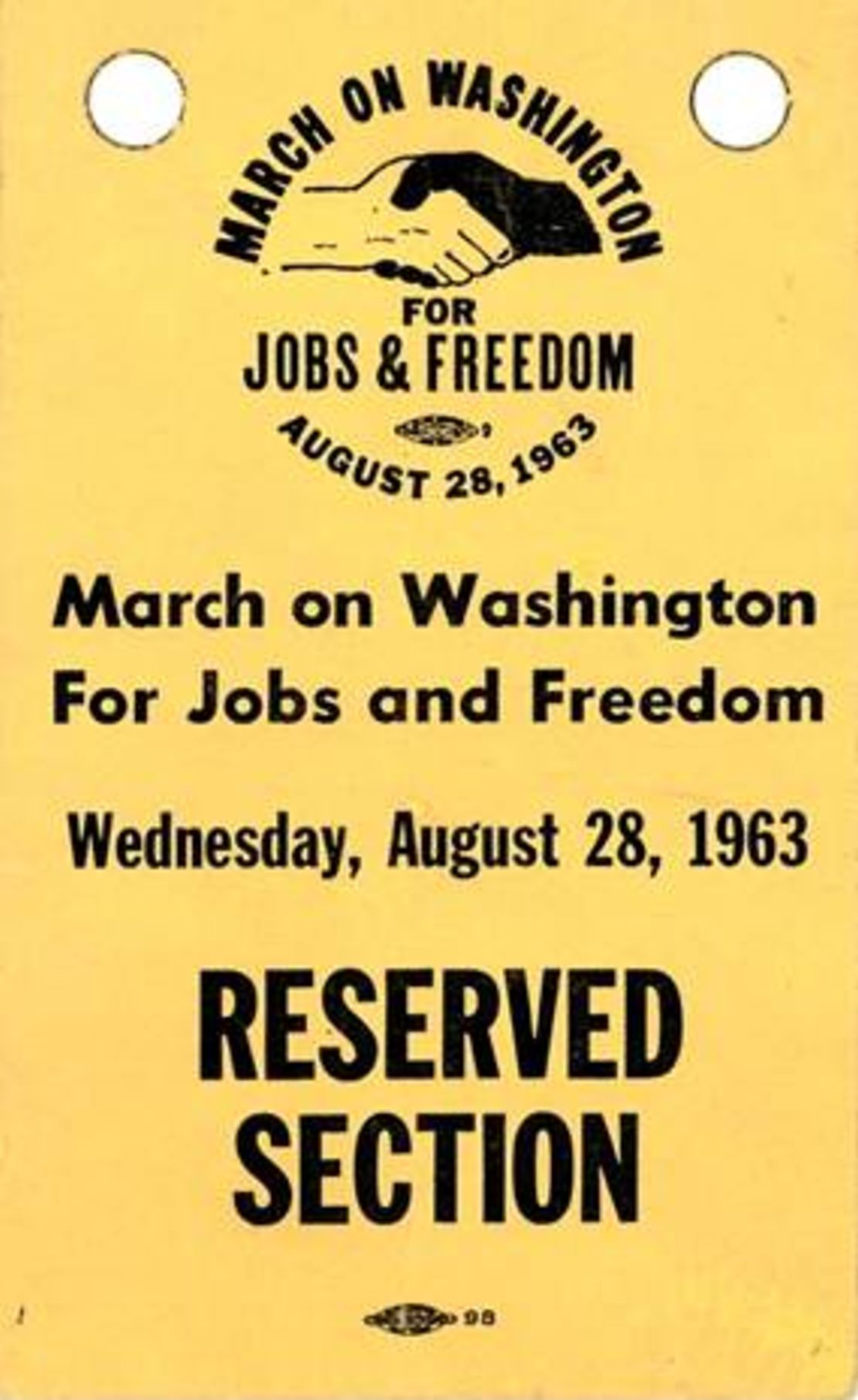

There was a growing mood among blacks that America was not protecting black people but instead was assassinating its leaders in a war. The demonstration planned for August 28, 1963, was touted as the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. But many factions within the movement were going to the march to demand that Kennedy and the federal government pass a civil rights bill and use its national police powers to protect black people in the same way it protected South Koreans and Cubans. The Southern filibuster by the old and “New” Southern states was no longer accepted as an excuse.

Some of the young people derisively called the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. “Dr. Coon.” They were ready for a change.

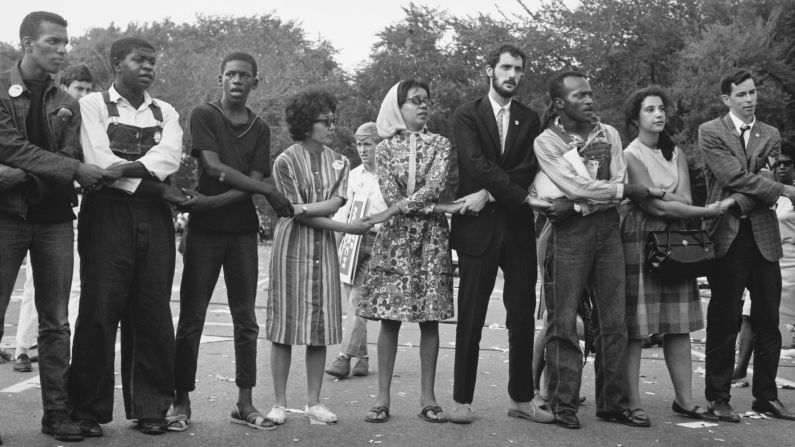

This was the context in which Patricia and I were invited by the Miami CORE chapter to travel as VIP guests on the Freedom Train that had been organized by the organizers of the March on Washington. The Freedom Train would leave from Jacksonville and make stops along the Florida East Coast Railroad route in Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia to pick up freedom fighters. Many of them were young, not yet in their 20s. Many were field workers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, who had been jailed and brutalized. They were angry in mood but also felt a building joyous excitement, singing freedom songs all along the way.

The speakers

When Patricia and I arrived in Washington, we learned that each of the leaders of the various civil rights organizations that were part of the freedom movement would be permitted to speak. The NAACP, SNCC, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the National Urban League, the Porter’s Union (A. Phillip Randolph had conceived of the idea of a March on Washington in 1941), as well as CORE.

We learned that CORE’s national director, James Farmer, had not arrived. Farmer had been in Louisiana to help the CORE chapter there and had not returned, nor had anyone heard from him. This was a frightful situation. NAACP Mississippi Field Secretary Medgar Evers had just been assassinated in June.

Patricia had gained national notoriety and respect within CORE because of the jail-in and because she had initiated the process which derailed the Kennedy administration’s plans to have the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach.

Patricia should have been the substitute speaker representing CORE to replace Farmer.

She had a reputation for standing up to authority – 49 years later, she even died from a battle with cancer with a defiant look on her face – and I believe the organizers did not select her to speak because they were afraid of what she would say.

She would have mentioned the violence toward and arrests of 200 youth, including herself, in Tallahassee, Florida, the beatings with chains of young people in Jackson, Mississippi, and violence against demonstrators in other places, but she wouldn’t have done it to incite violence in return. She was committed to confronting injustice head on with her words and with civil disobedience, not violence.

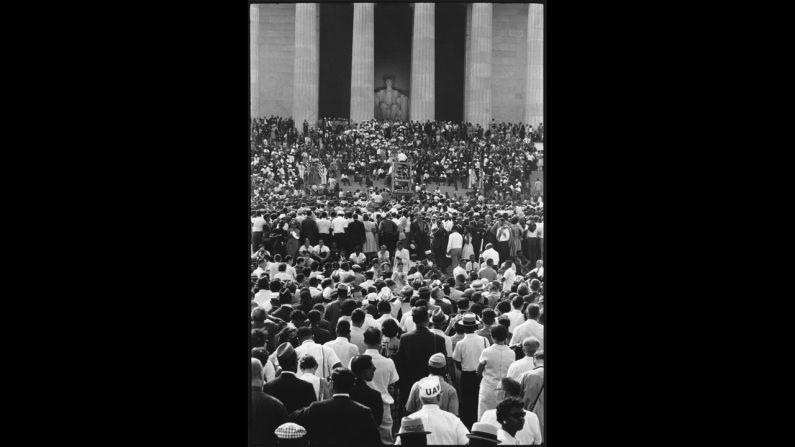

Patricia and I were assigned choice positions on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial a few feet from the speakers.

Floyd McKissick, a black attorney who organized CORE in North Carolina, was ultimately chosen to speak on behalf of CORE. (He later became CORE’s national director.)

I don’t remember what he said because of the day’s last speaker.

John Lewis was the SNCC speaker and he displayed the hot anger in his demeanor that the young activists were feeling. But I remember less about what he said and more about what he was not permitted to say – that we were going to march through Georgia like Sherman marched through Georgia. The organizers objected to the prepared text and he edited his remarks. I don’t remember much about what he actually said because of the last speaker.

UAW AFL-CIO labor leader Walter Reuther and other white speakers placed an emphasis on employment and housing.

Whitney Young, the national director of the National Urban League, had the most intelligent speech – stating the critical problem and the critical things that must be done. But the setting was not a college seminar.

We had come to the march feeling angry. Feeling hopeless about the United States of America.

We did not need a lesson plan. We needed a song. We needed church.

Five faces of the March on Washington

The last speaker

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was the last speaker.

Patricia and I heard gospel singer Mahalia Jackson cry out before he spoke, “Detroit! Give them the Dream Speech!”

And he sang “I Have A Dream…”

I can testify as a witness with my wife about the oceanic wave of love and hope that was felt by 200,000 people after Martin sang his song. That love and hope replaced the anger and hopelessness.

After the speech, Patricia and I were talking about how we were going to get to New York to go to CORE’s headquarters. A white couple with that rapture on their face said, “You people need a ride to New York? We will take you.”

And they took us straight to the national office of CORE on 38 Park Row.

The aftermath

That night, CORE’s national director Farmer finally appeared in the CORE office. Still scared to death, he described how local black supporters had arranged for him to travel hidden in a casket with a funeral director so he could make it to the airport and flee to New York. The White KKK in Louisiana had been out in force to assassinate him. (The white KKK was not the regular KKK, but a specific terrorist organization active in Louisiana, southwest Mississippi, and Canton and Meridian, Mississippi).

So, even in the immediate aftermath of the March on Washington, a stark and oppressive reality continued to confront us. But we didn’t feel alone.

Over the next five decades, we worked with several different civil rights organizations – from CORE to SNCC to the NAACP – but the names of the groups didn’t matter. What mattered was that we were all committed to opening up the courts, the ballot box, and the school systems with nonviolent social action.

Early on after the march our focus was on voting rights. I went to Mississippi in 1964 on behalf of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to monitor civil rights activities and the violence against civil rights activists for reports to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. While there, I worked with civil rights figures such as Robert (Bob) Moses and activists James Chaney and Michael Schwerner, who were later slain.

Patricia spent years as the CORE field secretary for North Florida and she was successful in registering disenfranchised blacks to vote at notable levels in the South.

We eventually moved to Miami, where I spent the majority of my career with the Miami-Dade County Community Relations Board and later as head of the county’s Office of Black Affairs, working with parents, teachers, students and clergymen to confront issues of poverty, discrimination, education and immigration. I literally walked the streets during race riots to try to instill calm to the community.

Patricia was a “professional volunteer,” championing civil rights causes and being a go-to person called upon by the black community. Education was her passion and she was above all else a mother to our three daughters. She led Title One and NAACP youth groups, and was determined to memorialize our history for youth through speaking and writing.

Ironically, she was the planning coordinator for the annual NAACP convention in Miami Beach in 1980, but was quick to participate in the rallies to boycott the city of Miami when the mayor snubbed Nelson Mandela when he was released from prison in 1990. Just as in 1963, Patricia refused to accept hypocrisy.

I will always consider myself a “freedom lawyer” and community activist because of my deeply held belief that you need to organize the community for freedom and social justice. I have spent the past few months in Tallahassee, Orlando, Sanford, Marianna, and other parts of Florida in support of civil rights and youth groups as they have tried to mobilize and navigate the aftermath of the Dozier boys’ school killings and the Trayvon Martin killing and Zimmerman verdict. I have also been working hard with local sheriffs to find new ways to combat the “schoolhouse to jailhouse” syndrome of our black youth.

What today’s young people must never forget is that it is possible to confront hate, racism and discrimination and transform our anger and hopelessness into hope and impact through our actions. That is what Patricia did, and that is what we should all aspire to do.

She may not have been permitted to speak at the March on Washington, but Patricia’s voice was never silenced. She and other foot soldiers will continue to make a difference for generations to come.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of John D. Due, Jr.