Story highlights

NEW: Husband of a victim says death penalty "would be too lenient" for Hasan

Penalty phase begins Monday, death penalty can be considered

Jurors "will decide whether you live or die," judge tells Hasan

Maj. Nidal Hasan is convicted of 13 counts of murder

A military jury on Friday convicted Army Maj. Nidal Hasan of 13 counts of murder and 32 counts of attempted murder in a shooting rampage at Fort Hood, Texas, making it possible for the death penalty to be considered as a punishment.

The jurors deliberated less than seven hours over two days before finding Hasan guilty on all charges in connection with the November 5, 2009, shootings at a deployment process center.

The Army psychiatrist admitted to targeting soldiers he was set to deploy with to Afghanistan, saying previously he wanted to protect the Taliban and its leaders from the U.S. military.

Under the rules of a military court-martial, the jury must return a unanimous verdict of premeditated murder for the death penalty to be considered as a punishment option. The jury is not required to tell the court whether they reached a unanimous verdict on the attempted murder charges.

The court-martial moves on Monday to the penalty phase, where Hasan – acting as his own attorney – will have the opportunity to address the jurors considering whether he should be executed for his actions.

As has been done nearly every day in the three-week court-martial, the judge asked Hasan if he had reconsidered defending himself as the case enters the penalty phase.

Jurors “will decide whether you live or die,” the judge, Col. Tara Osborn, told Hasan after reconvening the court Monday afternoon as part of the penalty phase preparation. “…I think it is unwise for you to represent yourself.”

Hasan told the judge he intended to continue acting as his own attorney.

Courtroom reaction

Inside the courtroom, the judge warned the audience in the gallery, including family members of those killed, before the verdict was announced that outbursts and reactions to the verdict would not be tolerated.

Hasan stroked his beard as the jury – a military panel of 13 senior officers – filed into the courtroom. He then looked at the head of the jury – a colonel – who affirmed a verdict had been reached.

Hasan showed no emotion as the verdict was read, a contrast to a handful of some of family members who cried or gave one another brief hugs.

“Today’s guilty verdict, rendered almost four years after the attack, is only a first, small step down the path of justice for the victims,” said attorney Neal M. Sher, who represents victims and families of those killed in a compensation claim against the government for failing to stop the attack.

Almost immediately after the attacks, there were widespread questions about how Hasan was evaluated, promoted and transferred to Fort Hood with plans to deploy to Afghanistan despite questions about his actions, including giving an academic presentation on the value of suicide bombings.

Sher renewed the call for the government to reclassify the shootings as a “terror attack” rather than workplace violence.

“Justice for the victims of Fort Hood will be done only when the government admits its mistakes, keeps its promises to ‘make the victims whole’ and comes clean about Fort Hood, ” Sher said. ” The victims, and the American people, are owed nothing less.”

The husband of Amber Bahr Gadlin, a former private who testified about the wounds she received during the attack, said the death penalty “would be too lenient” for Hasan.

“I would much rather see him sit in prison for the rest of his life. He shouldn’t be allowed to dictate what happens. He wants to motivate other terrorists,” Joshua Gadlin told CNN by telephone.

Hasan doesn’t call witnesses, give closing argument

On Thursday afternoon, the judge handed the case to the jury after Hasan declined to make a statement during closing arguments that followed 12 days of testimony.

The prosecution urged the jury to convict, saying the evidence showed that he believed he had a jihad duty to kill as many soldiers as possible.

“There is no doubt, as I said in the beginning, the accused is the shooter,” the prosecutor, Col. Steven Henricks, told the jury.

“The only question for you is … is this a premeditated design to kill?”

For more than 90 minutes, the prosecutor took the jury methodically through the evidence in the case, meticulously piecing together how he says Hasan prepared and planned for the attack.

Soldier on soldier attacks Fast Facts

Prosecutors have maintained that the American-born Muslim underwent a progressive radicalization that led to the massacre at the sprawling central Texas base.

“He did not want to deploy, and he came to believe he had a jihad duty to kill as many soldiers as possible,” Henricks told the jury.

Hasan picked the day – November 5, 2009 – because it was when the units he was scheduled to deploy with to Afghanistan were scheduled to go through the processing center, he said.

Hasan rested his case without calling a single witness or taking the stand to testify on his own behalf.

His decision not to offer a defense was an anticlimactic end to the trial in which prosecution witnesses, primarily survivors, painted a horrific picture of what unfolded inside a processing center during the attack.

A graphic FBI video during closing arguments

During closing arguments, prosecutors showed a graphic FBI video of the crime scene hours after the rampage, where bodies, blood and bullets still covered the floor.

As the video was shown to the jury, some of the family members of those killed fought back tears.

One woman laid her head on her husband’s shoulder, tears pouring down her cheeks, while another woman, a wife of a victim, left the courtroom.

For his part, Hasan watched the video, appearing to pay close attention.

Hasan, who has insisted that the jury not be allowed to consider lesser charges against him, said his attack on soldiers at Fort Hood was not an act of “sudden passion.”

Fort Hood victims feel betrayed

There was “adequate provocation” for the attack because the soldiers were going to participate in “an illegal war” in Afghanistan, Hasan told the military judge Wednesday, arguing against the jury being allowed to consider voluntary manslaughter or unpremeditated murder.

Prosecutors argued against the inclusion of lesser charges, saying the attack wasn’t carried out in “the heat of sudden passion,” and Hasan said he agreed.

The judge ruled that the jurors can consider a lesser charge of unpremeditated murder but not voluntary manslaughter. They can also consider unpremeditated attempted and other lesser charges, she ruled.

Hasan’s defense

Much has been made of Hasan’s defense or, as his stand-by attorneys have said, the lack of it. Judge Tara Osborn declined a request by Hasan’s attorneys to drop out of the case. The attorneys argued that Hasan was helping the prosecution put him to death.

There may be something to that claim.

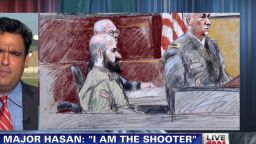

Hasan took credit for the shooting rampage at the outset of the trial, telling the jury during opening statements that the evidence will show “I was the shooter.”

Osborn barred Hasan from pleading guilty at the start of the court-martial. Under military law, defendants cannot enter guilty pleas in capital punishment cases.

The judge has refused to allow Hasan to argue “defense of others,” a claim that he carried out the shootings to protect the Afghan Taliban and its leaders from U.S. soldiers.

Perhaps as a way around that ruling, Hasan in recent days has leaked documents through his civilian attorney to The New York Times and Fox News that offer a glimpse of his justification for carrying out the attack. Among the documents was a mental health evaluation conducted by a military panel to determine whether Hasan was fit to stand trial.

“I don’t think what I did was wrong because it was for the greater cause of helping my Muslim brothers,” he told the panel, according to pages of the report published by The New York Times.

He also said, according to the documents: “I’m paraplegic and could be in jail for the rest of my life. However, if I died by lethal injection, I would still be a martyr.”

Prosecutors call dozens of witnesses

Military prosecutors called 89 witnesses and submitted more than 700 pieces of evidence before resting their case.

The judge excluded much of the evidence that the prosecution contends goes to the heart of the motive for the attack, including e-mail communications between Hasan and Anwar al-Awlaki, the U.S.-born cleric who officials say became a key member of al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. He was killed in a U.S. drone strike in 2011.

Osborn also declined to allow prosecutors to use materials they maintain showed Hasan’s interest in the actions of Army Sgt. Hasan Akbar, the American soldier sentenced to death for killing two soldiers and wounding more than a dozen others at the start of the Iraq war, an attack he said he carried out to stop soldiers from killing Muslims.

Along with the e-mails and the material related to Akbar, Osborn declined to allow the use of Hasan’s academic presentation on suicide bombings, saying “motive is not an element of the crime.”