Story highlights

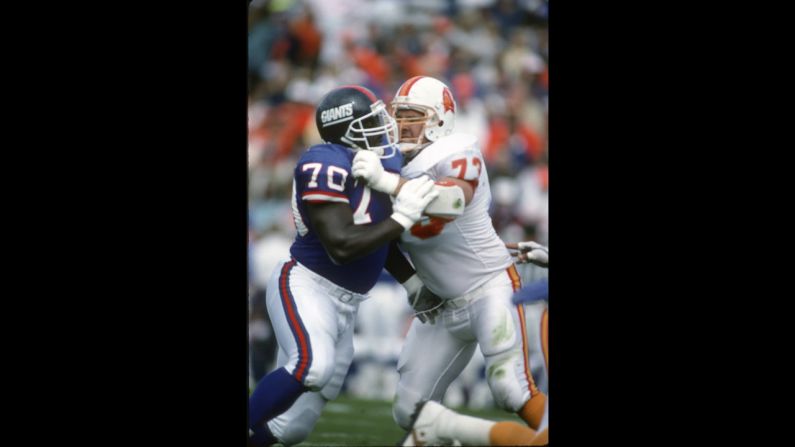

CTE has been seen in brains of athletes who have taken a lot of hits to the head

CTE can be diagnosed only after death, but a new study begins to describe symptoms

Athletes with the disease exhibit behavioral and mood problems, as well as memory issues

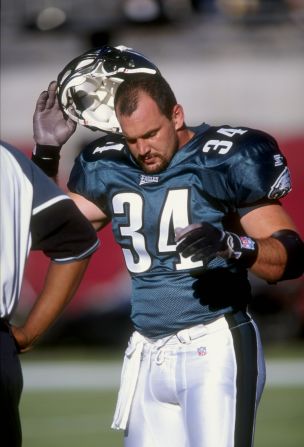

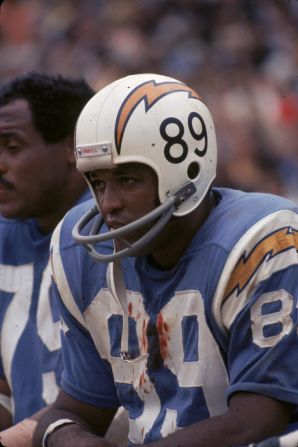

Ronney Jenkins cannot be sure whether chronic traumatic encephalopathy is clawing through his brain tissue right now, but he suspects that it is.

After all, he fits an emerging portrait of people diagnosed with the disease: a former professional football player who took lots of hits to the head – a couple knocked him out – and a life off the field that has begun to unravel.

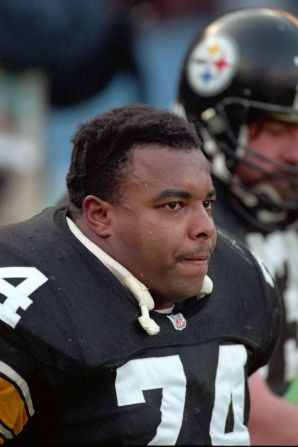

“My mood has changed,” said Jenkins, 36, a soft-spoken former running back who played for several teams, including the San Diego Chargers. “Sometimes I think I’m going crazy.”

Jenkins began to suspect CTE several years ago when an uncharacteristic dark mood and, occasionally, deep anger began to bubble up at unexpected times.

“I’d be talking to a cousin of mine, disagree with him, and I’d just want to do something to him,” Jenkins said. “I don’t know why I had those thoughts, but I wanted to hurt him.”

Jenkins cannot shake the feeling that these and other symptoms he has add up to CTE, but he will never be sure. The only way to diagnose CTE is after death – by analyzing brain tissue and finding microscopic clumps of an abnormal protein called tau.

“The problem is, people are diagnosing CTE clinically all over the place,” said Robert Stern, professor of neurology and neurosurgery at Boston University School of Medicine. “There is no framework to make that diagnosis while someone is alive.”

Stern and his colleagues want to change that. He is co-author of a new study that is beginning to describe what the disease looks like during life.

The study, published Wednesday in the journal Neurology, suggests that when CTE symptoms emerge at a young age, players more often exhibit behavioral and mood problems, whereas symptoms that begin later in life tend to show up as memory and thinking problems.

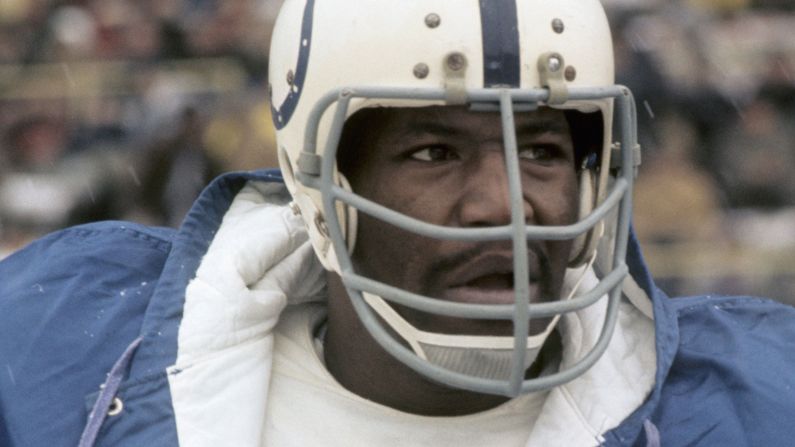

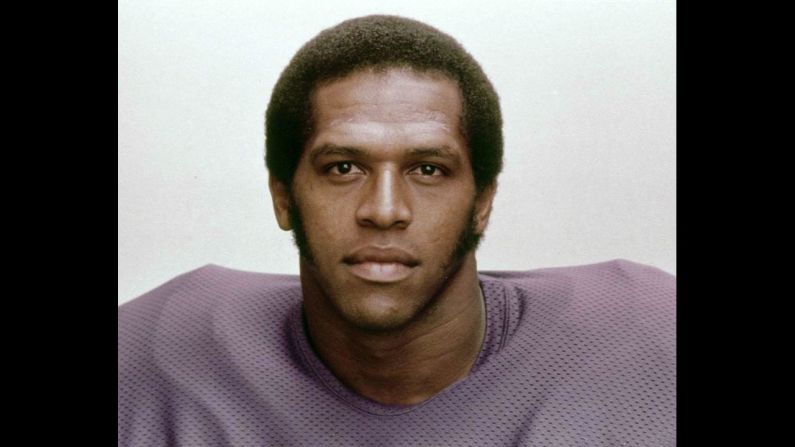

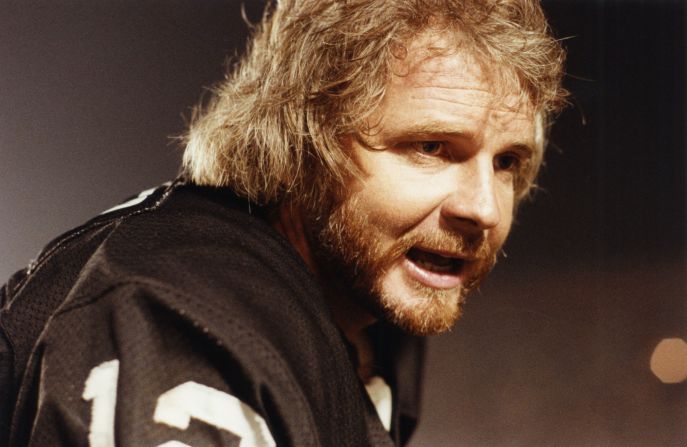

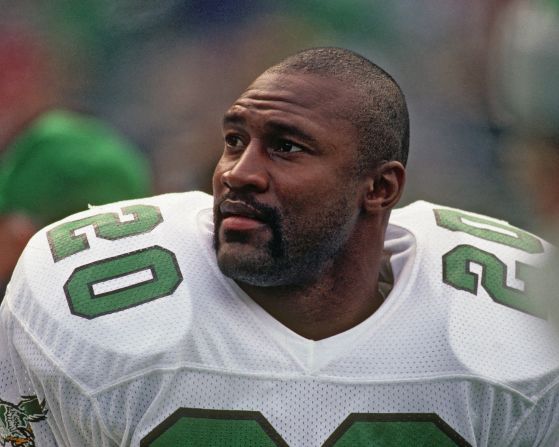

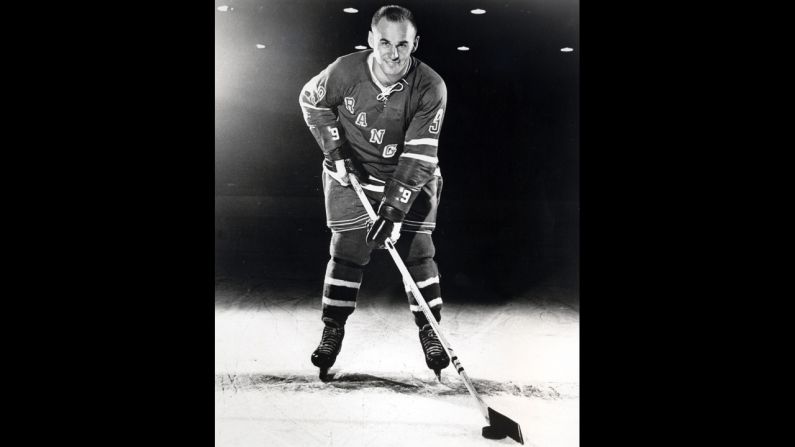

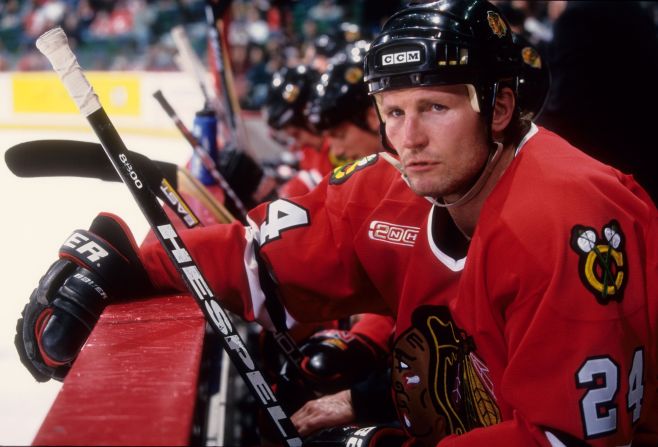

Family members and loved ones of 36 athletes – 29 football players, three professional hockey players, one professional wrestler and three boxers diagnosed with CTE after they died – were quizzed about, among other things, the nature of the players’ CTE symptoms and when they appeared.

A tale of two former NFL players – and their brains

According to those family reports, 11 players in the group first struggled with memory and decision-making, at an average age of 69.

Twenty-two players first exhibited mood and behavior problems like depression and hopelessness or violent, explosive behavior. Those players tended to be younger when they died, an average age of 51.

Three players did not display any symptoms before being diagnosed with CTE.

It is too early in the research to know why some symptoms crop up early and others later – and why the symptoms seem to diverge, or not show up at all, depending on the player. One theory among scientists is that where and how the damage manifests in the brain matters.

For example, tau, which tends to be peppered in particular areas of the brains of people diagnosed with CTE, could damage brain tissue at different stages of the disease, depending on the person.

“There is no specific order of changes in CTE; it’s on a case-by-case basis,” said Stern, who is also the co-founder of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy. “It could be that some people have more initial changes to (brain) areas that are more responsible for mood and aggression and impulse control.”

Symptoms could also be explained by other changes in the brain, associated with repetitive brain trauma, that have nothing to do with tau or CTE.

Junior Seau had brain disease that comes from hits to head

“This disease remains somewhat mysterious in terms of exactly what its causes are and how it’s expressed,” said Dr. Julian Bailes, co-director of the NorthShore Neurological Institute and a CTE researcher, who was not involved in the current study.

But Bailes says this study, though small and not generalizable for all cases of CTE, adds to current knowledge about the disease.

For example, the data did reveal other interesting patterns, particularly related to genetics.

The study participants with CTE were more likely than people without the disease to express the APOE gene, which is associated with slower recovery and worse cognition after traumatic brain injury; it’s also associated with later development of Alzheimer’s disease.

Stern and his colleagues know that their study sample is skewed: People who tend to donate a loved one’s brain to be studied for CTE also tend to suspect a problem. And there is no formula for how many hits (or what type of hits) tip the balance toward symptomatic disease. There has also been no examination of what role things like steroids or body weight may play.

Even with those caveats, Stern is confident that “eventually, clinicians will have the ability to diagnose the disease during life.”

In the meantime, former players like Jenkins are left in a fight against time and the progression of whatever brain disease their concussions may have wrought.

“I’m paying attention to things more,” he said, “and I’m more worried about my health.”

In the meantime, researchers of many disciplines are scrambling to define a disease that’s definition is elusive at best.

“For perspective, Alzheimer’s disease was first described in the first decades of the 1900s, and we still don’t have the ability to diagnose it definitively during life,” Stern said. “It still can’t be cured, prevented or even slowed down.”

Both Jenkins and Stern hope that for CTE, it will not be that long.

NFL Players Association, Harvard planning $100 million study