It’s the story everyone is talking about. Is marijuana harmful or helpful? CNN’s Dr. Sanjay Gupta cuts through the smoke on America’s “green rush” and journeys around the world to uncover the highs and lows of “Weed” Friday night at 10 ET.

Story highlights

In legalization debate, nation has moved from "if" to "how," drug policy expert says

White House calls legalization a "nonstarter;" new policy favors prevention over incarceration

Shift in opinion in last 6-7 years "doesn't feel like a blip," public policy professor says

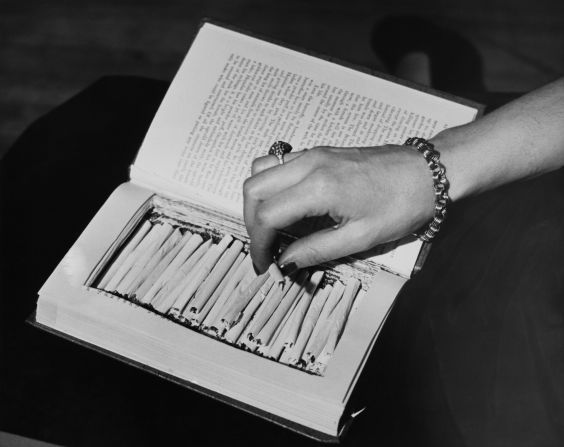

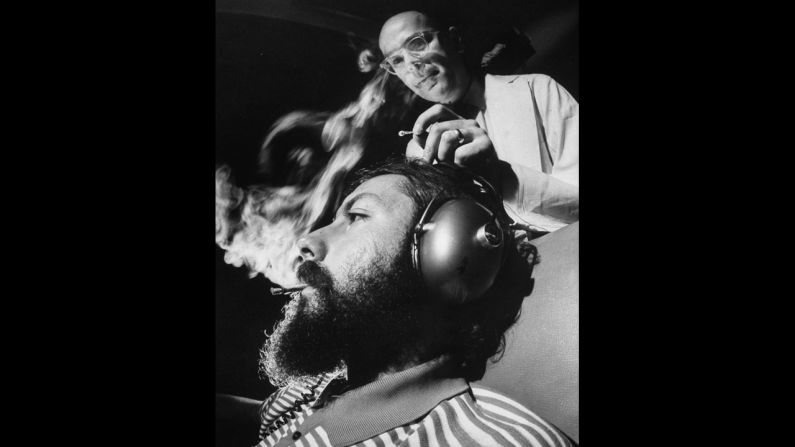

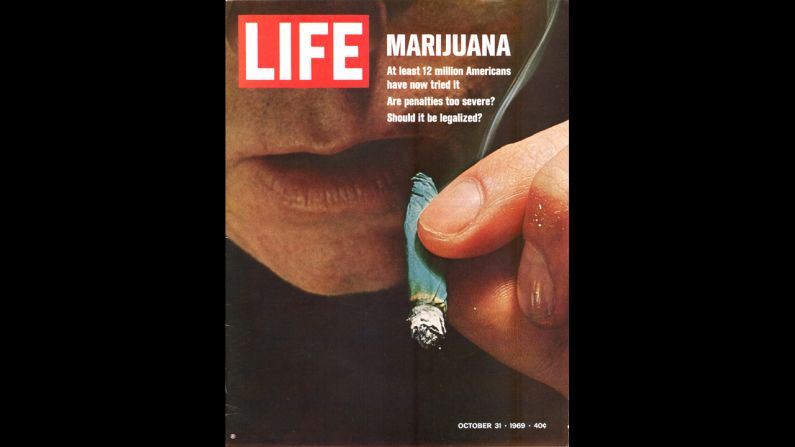

Poll says in 4 in 10 Americans have tried marijuana, up from 4 in 100 in 1969

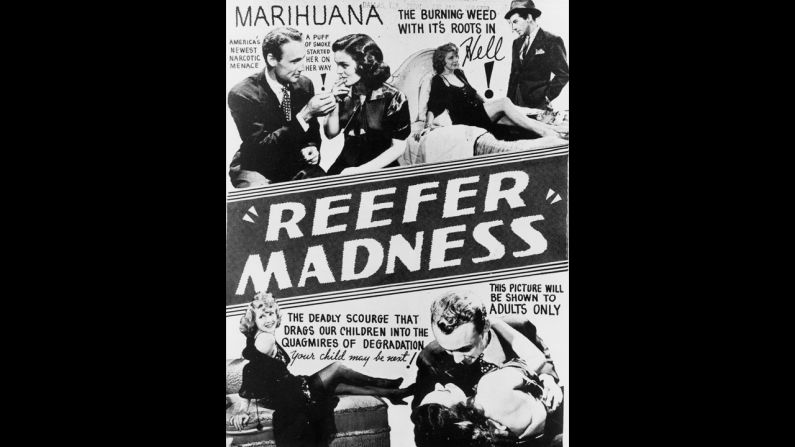

The question has dipped in and out of the national conversation for decades: What should the United States do about marijuana?

Everyone has heard the arguments in the legalization debate about health and social problems, potential tax revenue, public safety concerns and alleviating an overburdened prison system – but there isn’t much new to say.

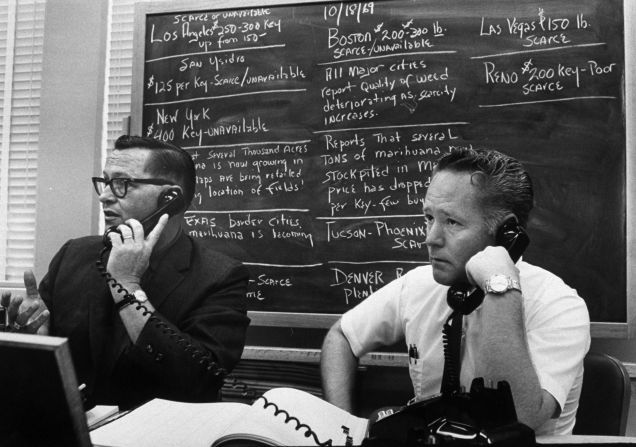

The nation has moved from the abstract matter of “if” to the more tangible debate over “how,” said Beau Kilmer, co-director of the RAND Drug Policy Research Center and co-author of “Marijuana Legalization: What Everyone Needs to Know.”

Changing attitudes about weed are part of a larger shift in the country’s collective thoughts on federal drug policy. Just this week, on the heels of CNN’s Sanjay Gupta reversal of his stance on medical marijuana, Attorney General Eric Holder announced an initiative to curb mandatory minimum drug sentences and a federal judge called New York City’s stop-and-frisk policy unconstitutional.

“Between Attorney General Holder’s announcement, the decision made on stop-and-frisk and Dr. Gupta coming out with his documentary, it was a big week for drug policy,” Kilmer said.

Peruse the Marijuana Majority website and you’ll see decrying pot prohibition is no longer confined to the convictions of Cheech and Chong.

Today’s debate involves an unlikely alliance that unites conservatives Pat Robertson and Sarah Palin with rapper Snoop Lion (aka Snoop Dogg), blogger Arianna Huffington and Jon Stewart of “The Daily Show.” In June, the U.S. Conference of Mayors cited organized crime, a national change in attitude, the efficacy of medical marijuana and exorbitant costs to local governments in its resolution supporting “states setting their own marijuana policies,” a stance similar to the one endorsed by the National Lawyers Guild and the Red Cross.

“I’m surprised by the long-term increase in support for marijuana legalization in the last six or seven years. It’s unprecedented. It doesn’t look like a blip,” said Peter Reuter, a University of Maryland public policy professor with 30 years experience researching drug policy.

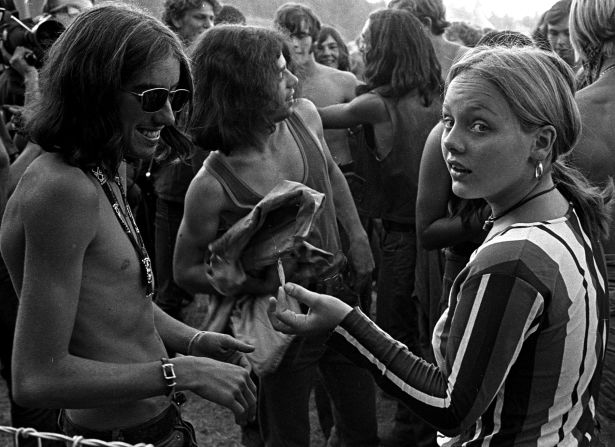

Reuter, who co-wrote the book “Cannabis Policy: Moving Beyond Stalemate,” said he believes two factors are spurring the shift in national opinion: Medical marijuana has reduced the stigma associated with the drug, making it “less devilish,” and the number of Americans who have tried the drug continues to rise.

Resistance fading

When Washington and Colorado legalized pot – with strict controls by established state agencies and a coherent tax structure – opponents weren’t able to raise the money to fight the initiatives, which Reuter considers an “important signal that the country is no longer willing to fight this battle.”

As important as the lack of resistance, Reuter said, is the subsequent response.

Though he doesn’t see federal legalization on the horizon, he noted that the White House could easily shut Washington and Colorado down, either via a Justice Department crackdown or an IRS prohibition on tax deductions for the purchase of marijuana, which Reuter said would be a “killer for the industry.”

Instead, this week saw Holder make his mandatory minimum announcement without so much as a word about what’s happening in the states.

Likewise, Congress has been reticent, Reuter said.

“It may be that everyone’s waiting to see what happens,” he said. “I take their silence to be some form of assent.”

In 1969, a Gallup poll showed 12% of Americans supported pot legalization, and it estimated that same year that four in 100 Americans had taken a toke. Last week, Gallup reported that number had spiked to almost four in 10.

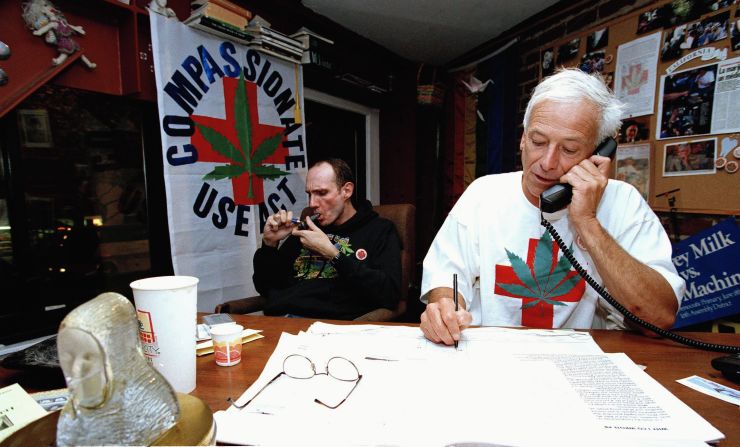

Gallup, Pew and CNN/Opinion Research Corp. polls conducted in the past three years indicate a nation evenly divided, and Gupta’s documentary plants him among a loud chorus that has sung the drug’s praises since California approved medical marijuana in 1996.

Since then, 20 other states and the District of Columbia have passed similar laws, while Colorado and Washington state have legalized it for recreational use – a move Alaska, California, Nevada and Oregon each twice rejected between 1972 and 2010, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

Sixteen states have decriminalized possession of personal amounts of marijuana since 1973, including Colorado, which approved decriminalization 37 years before voters legalized cannabis in 2012, according to the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws.

Mark Kleiman, a UCLA public policy professor who has been tapped to mold Washington’s legal pot industry, noted that even in states where recent ballot initiatives were shot down, there are telling results. Perennial red state Arkansas’ medical marijuana vote in November, for example, was a squeaker, failing 51% to 49%.

“When 49% of voters in Arkansas are voting for legal pot, we aren’t in Kansas anymore,” said Kleiman, who co-wrote “Marijuana Legalization” with Kilmer.

A savvier debate

The tone of the debate is also a sign that the country is nearing a tipping point at which public opinion effects political change. Rather than engaging in a simple yes-vs.-no debate about legalization, proponents are asking more nuanced questions: Should “grows” be large or small? What should the tax structure look like? Should potency be limited? Will the model involve for-profit companies? How will weed be distributed?

“The discussion over time – and I think it’s for the better – the discussion is starting to focus more on the details,” Kilmer said. “Before, nobody has ever really had to confront those decisions. … Those decisions are really going to shape the cost and benefits of policy change.”

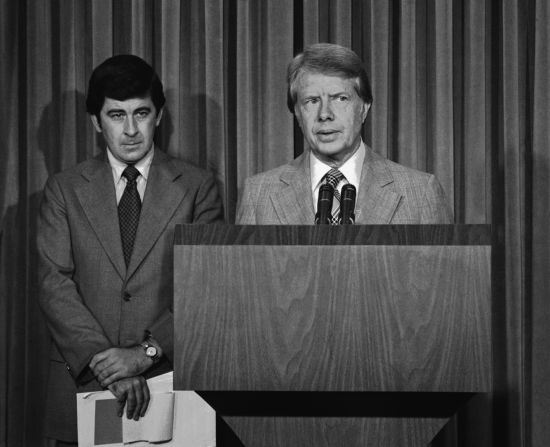

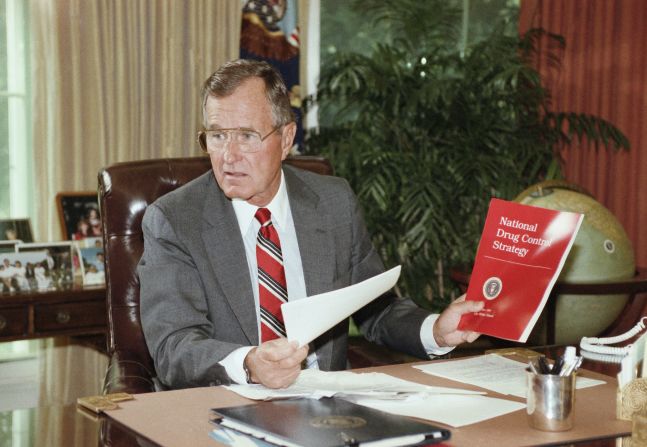

President Barack Obama’s drug czar, Gil Kerlikowske, said in 2010 that marijuana legalization was a “nonstarter,” an assertion the Office of National Drug Control Policy says holds true today.

The office emphasizes that the administration’s 2013 drug policy takes a new tack with the realization that America can’t arrest its way out of its longtime drug epidemic.

The White House policy, announced in April, favors prevention over incarceration, science over dogma and diversion for nonviolent offenders, the office says. Arguments for marijuana legalization, however, run counter to public health and safety concerns, the Office of National Drug Control Policy says.

The federal government may have a difficult time maintaining its stance, experts predict.

John Kane, a federal judge in Colorado, said in December he sees marijuana following the same path as alcohol in the 1930s. Toward the end of Prohibition, Kane explained, judges routinely dismissed violations or levied fines so trivial that prosecutors quit filing cases.

“The law is simply going to die before it’s repealed. It will just go into disuse,” Kane said. “It’s a cultural force, and you simply cannot legislate against a cultural force.”

Kleiman, who is also chairman of the board for BOTEC Analysis Corp., a think tank applying public policy analysis techniques to the issues of crime and drug abuse, said the federal government may have tripped itself up in the 1970s by classifying marijuana as a Schedule I drug with no medicinal use and a high potential for abuse.

If the government had made it Schedule II, the classification for cocaine and oxycodone, 43 years ago, it would be easier today to justify a recreational ban, he said.

States to take lead

Kleiman said the infrastructure he is helping establish in Washington could provide a model for other states, but ideally, he’d prefer a model that involved federal legalization and permitted users to either grow their own marijuana or patronize co-ops.

“All the stuff I want to do you can’t do as long as it’s federally illegal,” Kleiman said. “By the time we get it legalized federally, there will be systems in place in each state,” which will make uniform controls at a national level tricky.

The push for legalization has gained momentum, though, he said, and he doesn’t foresee it moving backward. In 10 years, proponents might even move politics at a national level, he said, though predictions are problematic so long as pot prohibition endures.

“It’s sustained right now. Whether it’s going to be sustained is another question,” he said.

In the meantime, states are expected to continue to lead the charge. Alaska could put a legalization ballot before voters next year, while Maine, Rhode Island, California and Oregon may give it a shot in 2016, when the presidential election promises to bring younger voters to the polls.

“I think a lot’s going to depend on how legalization plays out in Colorado and Washington – also, how the federal government responds,” Kilmer said. “We still haven’t heard how they’re going to address commercial production facilities in those states.”

The next White House administration could easily reverse course, just as it could on mandatory minimums, Kilmer said, but while pot’s future is nebulous, the nation’s change in attitude – not only since the 1960s, but even since a decade ago – is clear. That makes proponents hopeful, if reluctant to make predictions.

“I didn’t see this (shift in opinion) coming, and I think that’s true of my collaborators,” Reuter said. “So much for experts.”