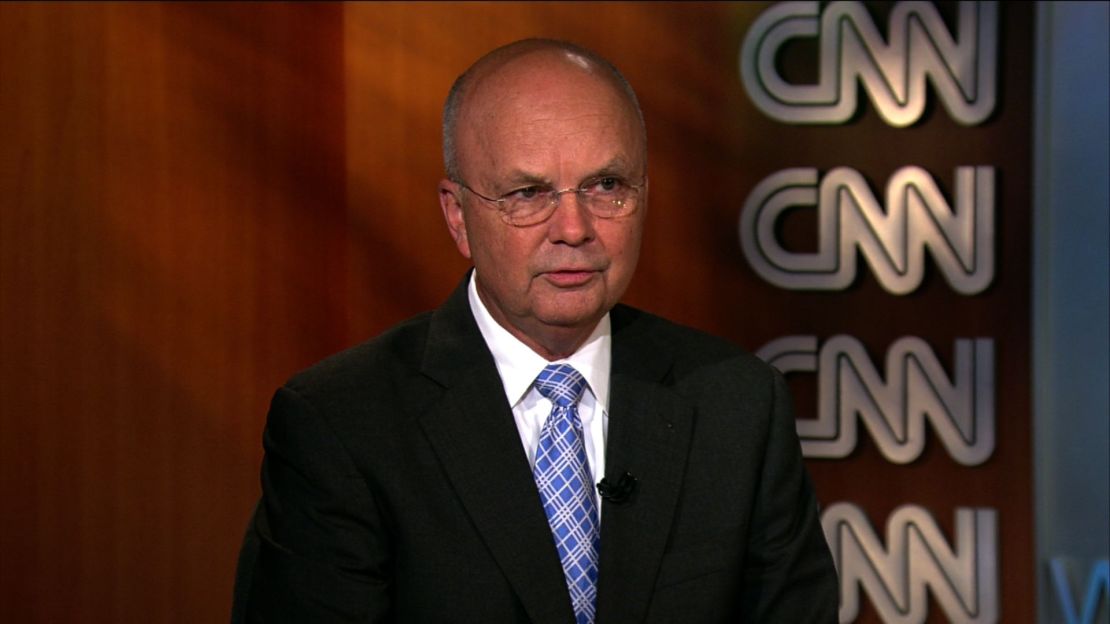

Editor’s Note: Gen. Michael V. Hayden, a former National Security Agency director who was appointed by President George W. Bush as CIA director in 2006 and served until February 2009, is a principal with the Chertoff Group, a security consulting firm. He is on the boards of several defense firms and is a distinguished visiting professor at George Mason University. This is the second in a series of pieces by Hayden on the Edward Snowden case.

Story highlights

Michael Hayden: Many have misconstrued NSA access to phone calls

He says agency has information on calls but not content of the calls

Hayden says agency needs metadata on calls to track terrorists

He says NSA was criticized in wake of 9/11 for not detecting the plot

“Any analyst at any time can target anyone. Any selector, anywhere … I, sitting at my desk, certainly had the authorities to wiretap anyone, from you or your accountant, to a federal judge, to even the President. …”

Thus spoke – this time not Zarathustra, the Persian prophet – but former National Security Agency systems administrator Edward Snowden.

To be sure, Snowden was reaching for dramatic effect, but if his words were true, he would have been violating not only the laws of the United States, he would also have been violating the laws of physics. He had neither the authority nor the ability to do what he has claimed he could do.

To determine what we think of Snowden’s allegations about the NSA’s activities, we should have a clear idea of what the NSA is actually doing, not what Snowden implies or alleges or what some 24/7 networks allow their commentators to proclaim.

The confusion is not entirely Snowden’s fault. The story has been so badly mangled by the media that one of The Washington Post’s “exposes” (on the PRISM program) has been rewritten, without benefit of announcing corrections, on the newspaper’s website.

So let us begin where Snowden did – with the “telephony metadata” or business records program.

It is clear that the NSA has access to large numbers of calling events that Americans create: who called whom, when and for how long, but neither the location of the communicants nor certainly the contents of the call.

Why in heaven’s name would they want this “metadata” – the term of art applied to the externals of a communication, somewhat like what is on an envelope as opposed to the content of a letter?

I’ll tell you why. Before the attacks of 9/11, Nawaf al-Hazmi and Khalid al-Mihdhar (part of the al Qaeda “muscle” on the plane that struck the Pentagon) were living in San Diego. From there on several occasions they called an al Qaeda safe house in the Middle East whose communications were targeted by American intelligence.

The NSA intercepted a series of these calls and created intelligence reports on several of them. But nothing in the physics of these intercepts or in the contents of these calls (even looking at them in retrospect) told us that these two known terrorists were in the United States.

After the 9/11 attacks, the intelligence committees of the U.S. Congress formed a joint inquiry commission to determine what had gone wrong. One of the commission’s findings was to criticize the “NSA’s cautious approach to any collection of intelligence relating to activity in the United States.”

Years later, in his 2008 book, “The Shadow Factory,” James Bamford – a chronicler and inveterate critic of NSA activities and, it should be added, a participant in a lawsuit against the agency for its post-9/11 activities – wrote about al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar that “the Agency never alerted any (emphasis his) other Agency that the terrorists were in the United States and moving across the country toward Washington.”

To be sure, the NSA never knew they were in the United States, but a career critic of alleged NSA privacy violations (Bamford) thought the agency did and should have known these two terrorists were in (that’s my emphasis) this country and the Congress of the United States believed the NSA too “cautious” about intelligence in (my emphasis again) America.

The metadata program was an attempt to deal with this challenge with the lightest possible impact on American privacy. After all, the Supreme Court had determined decades earlier (Smith v. Maryland, 1979) that metadata carried no expectations of privacy.

Thus, it seemed the perfect approach. Properly used, metadata collection was not about targeting Americans. It was about determining who in America deserved (in all meanings of the word: legally, morally, operationally) to be targeted.

And, as Steve Bradbury, the acting head of the Office of Legal Counsel at the Justice Department during this period, has pointed out, “At least 14 federal judges have approved the NSA’s acquisition of this data every 90 days since 2006 under the business records provision of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA).”

Billions of records are retained by the NSA under this program, but these records are accessed only under strict controls. No data mining engines or complex logarithmic tools are launched to scour the data for abstract patterns.

Instead, the data lies fallow until the NSA can put a question to it based on a predicate related to terrorism and only terrorism. A little more than20 people at the NSA get to do this, under close supervision, and the agency reports that this happens about 300 times a year.

Let me describe a possible example of a “terrorist predicate.” Let’s say that somewhere in the world American intelligence comes across an individual it has good reason to believe is an al Qaeda operative, and he has a cell phone in his possession.

Under this authority, the NSA could take the cell phone number and use a computer simply to ask that ocean of metadata, “Is there any activity in here related to what we now believe to be a terrorist telephone?” And if a number in the Bronx timidly raises its hand (so to speak) and answers, “Why, yes, I routinely communicate with it,” the agency gets to ask, “And who do you and your friends talk to?”

That’s it! If there is anything more to be done, the agency (actually, far more likely, the FBI) has to go back to court to dig any deeper into American information.

This is hardly the East German Stasi, but there may be some in America who are still discomfited by it.

Fair enough. But folks should object based on facts rather than on the oft heard and amazingly misinformed commentary in some of the media that claims the NSA can then go back and listen to these calls in its database – listen to calls that have never been recorded and which, incidentally, are protected by the U.S. Constitution.

And for those who still object, please keep in mind that, if the metadata program had been in effect in the summer of 2001, al-Hazmi and al-Mihdhar would likely have been rolled up, the plane that hit the Pentagon would not have had these jihadists available for the hijacking and the entire 9/11 enterprise might have been scrapped by al Qaeda.

In my next column, I’ll tackle: What of the PRISM program, the collection of Internet content with the compelled cooperation of American firms? And how is that enterprise viewed here and abroad?

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Michael Hayden.