Editor’s Note: David M. Perry is an associate professor of history at Dominican University in River Forest, Illinois. His blog is How Did We Get Into This Mess. Follow him on Twitter.

Story highlights

David Perry: Plan to reconstruct Ottoman era barracks in Taksim Square revealed deep divisions

When Atatürk modernized Turkey, he says, many resented parting with old Islamic ways

Perry: Prime minister and his AKP party exploited that resentment in their rise to power

The meaning and relevance of the Ottoman past remains a powerful question, he says

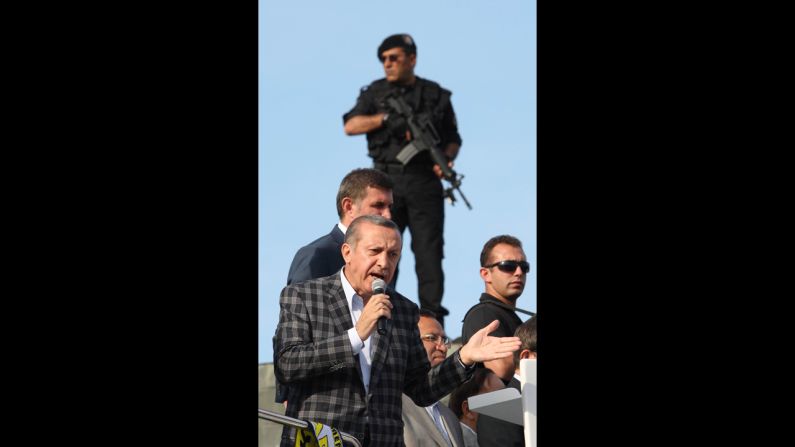

In 2012, Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan defended the highly divisive renovation of Taksim Square in central Istanbul by invoking history. Referring to the plan to build a replica of a monumental 19th century Ottoman army barracks that once stood there, he said: “We are working to bring back history that has been destroyed. …We will unite Taksim with its history.”

As it turned out, Erdoğan’s attempt to unite Taksim with its history has revealed very deep fissures in Turkish culture. Starting at the end of May, more and more opponents of the renovations began gathering in the square. Protests evolved into a general condemnation of the government, becoming more chaotic, with police attacking protesters with water cannons and tear gas. Thousands have been injured and at least two protesters and one police officer have died. The demonstrations have spread to other cities.

Although Erdoğan has claimed to be open to “democratic demands,” he has denied the legitimacy of all the public unrest. A day after the prime minister proposed talks with protesters, bulldozers and riot police swept through the square and blanketed the area with tear gas. Chaos and standoffs between police and protesters continue.

Turkey looks for ‘legitamite protestors’

Debating the causes of the conflict, some commentators focus on the role of Islam in Turkey; others emphasize disagreements about the nature of Turkish democracy, the lack of civil liberties, or the nascent environmentalist movement, which was stirred by plans to take down trees in the square’s Gezi Park.

All these played a role in igniting unrest, but the issues surrounding the reconstruction of the Ottoman Taksim Military Barracks in particular point to deep unresolved historical tensions within the Republic of Turkey. The protesters and the government are engaging not only in a battle for their park and perhaps their country’s future, but also for control over the past.

When Mustafa Kemal Atatürk founded the Republic of Turkey in 1923, after years of war, he was embraced by a population eager to return to the days of the great Caliphs. But Atatürk chose, instead, to modernize, Westernize, and secularize the country. He disbanded the Caliphate, secularized the education system, outlawed Sufi Islam, enforced gender equality, Westernized the Turkish alphabet, and famously banned the fez. But these radical and sometimes ruthless steps, especially those that ran counter to perceived Islamic mores, engendered deep resentment and resistance.

Opinion: From victim to villain, Erdogan’s unfinished transformation

In the last decade, Erdoğan and his Justice and Development Party, known as AKP, have exploited that resistance as an element in their rise to power. Under AKP rule, the Ottoman past has re-emerged in a culturally powerful way. The movie “Fetih 1453,” a highly dramatized account of the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, had the biggest budget in the history of Turkish cinema, an investment handsomely rewarded by its box office returns.

Turkish television is full of Ottoman-era dramas and soap operas, including the wildly successful “Magnificent Century,” set in the era of the famous emperor Suleiman the Magnificent. More and more aspects of elite Turkish culture embrace Ottoman architecture, fashion and even food. But according to some opponents of the AKP, the cultural embrace of Ottoman history promotes a political agenda of regional domination.

The decision to rebuild a symbol of Ottoman militarism, the Taksim Military Barracks, like the decision to name the new Bosphorus bridge after Sultan Selim I, conqueror of the Arab world, feeds this speculation. In popular Turkish culture, the Taksim Barracks are associated with the killing of Christian army officers in 1909, while the Alevis – a large minority group in Turkey – remember Selim I as the murderer of their people. Thus, both bridge and barracks pit one view of history against another.

But the Ottomans were not merely expansionary conquerors, nor were they generally devoted to Islamic purity. At their best, the Sultans ruled over a surprisingly pluralistic society that enabled people of diverse religions and ethnicities to flourish and live in relative autonomy. Both non-Turkish Muslims and non-Muslims rose to great heights of political power. Jews fled from Christian persecutions into Ottoman territory. In the wake of the riots, elements of this Ottoman legacy have begun to emerge as well.

Devrim Evin, who played Sultan Mehmet II in “Fetih 1453,” declined to join Istanbul’s formal celebration of the 560th anniversary of the conquest of Constantinople. Instead, joining actors from “Magnificent Century,” he went to Gezi Park to support the protests. Thus, the protesters were treated to actors playing Mehmet the Conqueror and Suleyman the Magnificent marching and tweeting alongside them.

Evin, like Erdoğan, invoked Ottoman history. He said, just before the violence began, that Mehmet preserved the Orthodox basilica Hagia Sophia when he took the city. “Such were our ancestors,” he said. “They preserved things, did not destroy or tear down.”

As with any turbulent situation, it’s hard to predict what will happen in Gezi Park or within the broader cycles of social unrest emerging in Turkey. Erdoğan looks unlikely to back down, at least not without a huge loss of face. Because the AKP has enjoyed broad popular support for its agenda, it will require internal pressure from within the movement to push Erdoğan toward a consensus settlement.

But even if issues involving Taksim Square are eventually resolved without greater riots and brutality, the question of the meaning and relevance of the Ottoman past remains powerful.

In “Fetih 1453,” Mehmet proclaims, “Making history is no job for cowards.” The events unfolding in Taksim remind us that remembering history can be just as dangerous as making it.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of David Perry.