Editor’s Note: Kerem Oktem is research fellow at the European Studies Centre, St Antony’s College and an associate of Southeast European Studies at Oxford. Karabekir Akkoyunlu is researcher at the London School of Economics where he focuses on socio-political change in Turkey and Iran.

Story highlights

Turkey is no Egypt and Erdogan no Hosni Mubarak, Kerem Oktem and Karabekir Akkoyunlu write

But the trigger for the rapid spread of events was the prime minister's inability to listen to critique and disagreement

One might wonder why a government that enjoys popular support is unable to tolerate a few protests

That the prime minister sees criticism of projects is a sign of insecurity and could yet prove his undoing

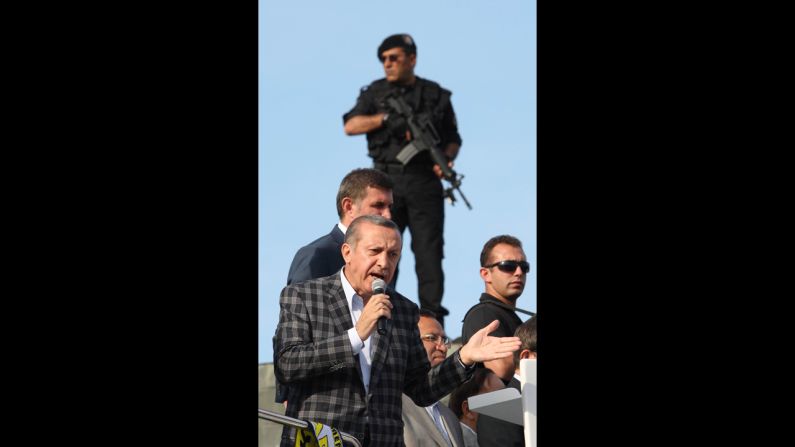

Turkey is no Egypt and Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan no Hosni Mubarak. This is not a “Turkish Spring,” but a message to an elected leader to reign in his hubris and his divisive politics.

These are some of the central messages, which both Turkish commentators (ourselves included), and the international media have brought across.

Erdogan still has a choice, as the Financial Times reminds us, between rising to the highs of statesmanship of former French President Charles de Gaulle or spending his remaining political life as a Turkish likeness of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The question now being asked in Turkey’s capital Ankara, on Istanbul’s Taksim Square and in the occupied Gezi Park, where the initial protests started, is whether Erdogan has the political determination and the nerve to accept the demands of the initial protestors.

WATCH MORE: ‘Lady in red’ does not want to be a symbol

That would mean giving up on his personal dream to build the Ottoman barracks on the park and turn it into a shopping mall. His track record would suggest otherwise.

Probably the single most important trigger for the rapid spread of events was the prime minister’s inability to listen to critique and disagreement, and the way in which this inability has manifested over the last few years.

His rhetoric has been spiraling out of control and has ranged from lecturing women on how many children to bear to calling everyone who enjoys drinking a beer in a sidewalk cafe an alcoholic.

READ MORE: Erdogan defends handling of protests

Further, the country has used an excessively violent policing strategy, with which the government has oppressed almost all legitimate protest by trade unions, political movements and student groups.

All this extreme use of force looks awkward in a country where the government was re-elected with almost 50% of the vote only two years ago and where its macro-economic development indicators tell a story of unfettered progress.

One might wonder why a government that still enjoys such popular support is unable to tolerate a few protests here and there and is incapable of giving into what are often very reasonable demands against the excesses of environmental degradation and rent-based urban renewal policies.

Why would an elected prime minister, who has, until now, been respected abroad and at home, use the force of his security apparatus to crush so brutally any popular dissent, which is far from threatening his place at the top of Turkey’s political system?

WATCH MORE: The week that changed Turkey

Part of the answer lies in Turkey’s recent record of undemocratic manipulations to bring the government down. Kemalist elites, the military, the judiciary and the so-called “deep state” rogue elements acting within the visible state structures, conspired to terminate the Justice and Development Party’s (AKP) government from the very moment of its first election in 2002.

Ever since, the party had to face several attempts at power grab, from an ultra-nationalist conspiracy in the mid-2000s based on unresolved assassinations of Christian missionaries and the murder of Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink to the so-called Republican Marches against the election as President of Abdullah Gul to the Constitutional Court’s only narrowly averted closure case against the ruling party in 2008.

All of these experiences have led Erdogan and many members of the AKP government to look at Turkish politics through the prism of conspiracies, and the blame for this shift does not lie only with the AKP.

More significantly though, the manipulations they faced from the judiciary and the military have led the AKP government to fill both institutions with sympathizers, thereby removing the already weak system of checks and balances in Turkey.

READ MORE: Erdogan: Leader or ‘dictator’?

The confluence of both the conspiratorial mind-set and a lack of checks and balances has created the ground for Erdogan’s unhealthy mix of extreme self-confidence on the one side and his insecurity vis-à-vis criticism on the other.

The shopping mall in Gezi Park, the third bridge over the Bosporus, the new airport and a canal project that is supposed to connect the Marmara and the Black Sea have been devised without any consultation and public debate.

That the prime minister sees any criticism of these projects as manipulations by domestic and external enemies is a sign of his insecurity. That he failed to grasp that the Taksim protests were not started by undercover military agents, die-hard Kemalists, Iranian agents or Syrian provocateurs may yet mark the beginning of his undoing.

Will Erdogan be able to arrive at a sober consideration of the situation and give in to the demands of the protestors in Gezi Park, call an impartial review of police brutality and reconsider the heavy policing strategies, which have turned Turkey into a police state?

WATCH MORE: Turkey as a ‘pivotal’ country

If he did, he would still have a chance to enter Turkish history as a statesman who carried his country into the 21st century, disassembled the military’s tutelage, ended the Kurdish War and granted long-fought-for rights to the country’s largest minority, the Kurds.

If he fails, and drags the country towards polarization and political unrest, his government, the economy and hence the people of Turkey will lose.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Kerem Oktem and Karabekir Akkoyunlu