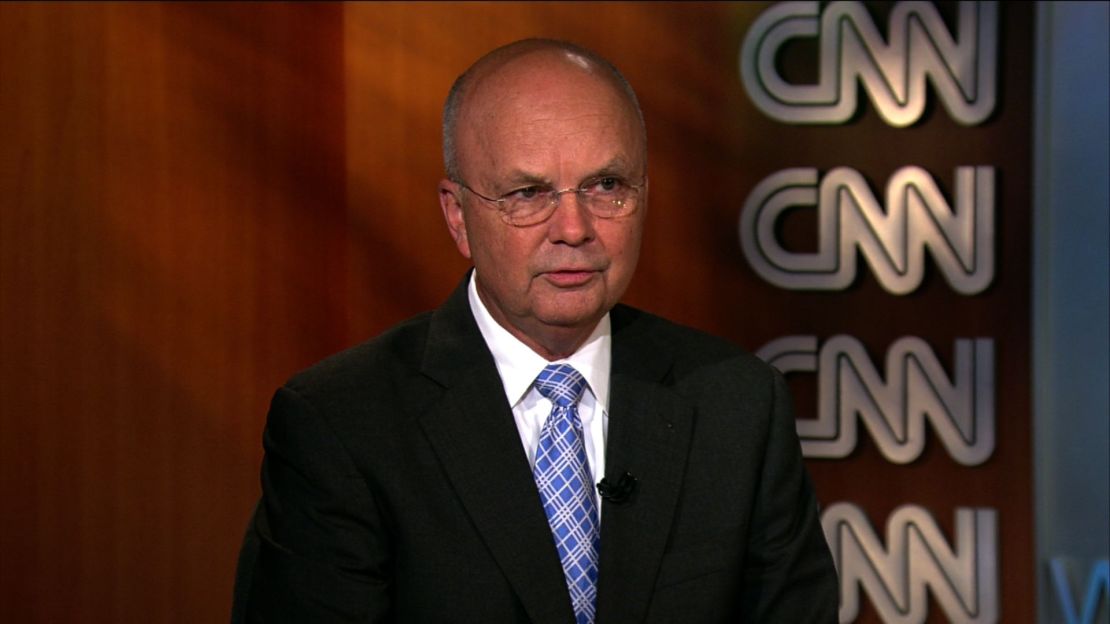

Editor’s Note: Gen. Michael V. Hayden, who was appointed by President George W. Bush as CIA director in 2006 and served until February 2009, is a principal with the Chertoff Group, a security consulting firm. He serves on the boards of several defense firms and is a distinguished visiting professor at George Mason University.

Story highlights

Ex-CIA director Hayden says the AP, Fox leaks were serious, and related to sources of intelligence

He says even though leaks were damaging, Obama administration went too far in its probes

He says there's a need to balance protecting secrets against freedom of the press

When I was at CIA or NSA, my public affairs staff would sometimes enlist me to intervene with an editor to stop the publication of what we viewed to be classified information.

I would invariably begin the conversation with the journalist by pointing out that I knew that, “We both have a job to do protect American security and liberty, but how you’re about to do yours is going to make it harder for me to do mine.”

That introduction reflected my true feelings, so—like most Americans—I am conflicted about the current row over protecting press freedom and protecting national secrets.

Let me be clear. The two prominent cases being debated were indeed serious leaks, because they touched upon sources, not just information.

In the case of the Associated Press report on a Yemen-based bomb plot, the source had apparently penetrated an al Qaeda network and there were hopes that he could continue to be exploited.

In the Fox News report on North Korea’s intention to test a nuclear weapon, James Rosen told us not just that the United States judged that Pyongyang would respond to impending sanctions with a test. He pointedly added that a source in North Korea had told us so.

These kinds of stories get people killed. While at CIA I recounted to a group of news bureau chiefs that, when an agency presence in a denied area had been revealed in the media, two assets had been detained and executed. The CIA site there wrote: “Regret that we cannot address this loss of life with the person who decided to leak our mission to the newspapers.”

And, since the Yemen source appears to have actually been recruited by a liaison partner, the impact of a leak goes far beyond our own service. In that same talk with bureau chiefs, I pointed out that several years before 9/11, one chief of station reported that a press leak of liaison intelligence had “put us out of the (Osama) bin Laden reporting business”.

In both stories, investigations were in order. Journalists, of all people, should understand the need to protect sources and relationships.

But the investigations have been very aggressive and the acquisition of journalists’ communications records has been broad, invasive, secret and—one suspects—unnecessary.

A quick survey of former Bush administration colleagues confirmed my belief that a proposal to sweep up a trove of AP phone records or James Rosen’s e-mails would have had a half-life of about 30 seconds in that administration. And, although Rosen seems to have worked his source with tradecraft and elicitation techniques more reminiscent of a case officer than a press conference, charges of co-conspiracy and flight risk are quite a stretch.

If this had been a Predator strike rather than an investigation, we would have judged the target (leaks and leakers) to have been legitimate, but the collateral damage (squeezing the First Amendment and chilling legitimate press activity) to have been prohibitive.

Which brings me back to being conflicted and to a sense of resignation that this legitimate free press-legitimate government secrets thing is a condition we will have to manage, not a problem that we will solve.

When the press decides to publish something that the government considers classified, it is assuming for itself an inherently governmental function. And as David Ignatius once pointed out, “We journalists usually try to argue that we have carefully weighed the pros and cons and believe that the public benefit of disclosure outweighs any potential harm. The problem is that we aren’t fully qualified to make those judgments.”

True enough, but no one who has served in government would claim that the public release of every document marked with a classification stamp would actually harm American security. Over-classification is common.

Government confuses things further with controlled releases of formerly classified data for both policy and political reasons. So many anonymous government officials have commented on drones and targeted killings in recent years that I told a Senate committee last summer that I simply did not know what of my personal knowledge of those programs I could or could not publicly discuss.

If there exists a body of information that can fairly be labeled “publicly known but still officially classified,” the protection of truly secret data will be eroded. When lines are not bright, it is more likely that even well intentioned people will end up on the wrong side of them.

The problem promises to get harder, not easier. While at CIA I asked my civilian advisory board to consider whether America would be able to conduct espionage in the future within a political culture that seemed to every day demand more transparency and more public accountability from every aspect of national life. They weren’t optimistic.

Beyond this cultural trend, modern technology arms inquisitive journalists with powerful tools to gather and link disparate data, to turn what were once globally dispersed shards of glass into revealing mosaics. Many things intended to be secret, like the airlift of Croatian weapons to Syria, simply don’t stay that way.

So, how do we limit the damage? Well, journalists will have to expand the kind of sensitivities to the national welfare that some already show. In those calls I made to slow, scotch or amend a pending story, most on the other end of the line were open to reasonable arguments. In one case a writer willingly changed a reference that had read “based on intercepts” to “based on intelligence reports,” somewhat amazed that that change made much of a difference. (It did.)

The government may also want to adjust its approach to enforcement. The current tsunami of leak prosecutions is based largely on the Espionage Act, a blunt World War I statute designed to punish aiding the enemy. It’s sometimes a tough fit. The leak case against former National Security Agency employee Thomas Drake collapsed of its own overreach in 2011.

Perhaps in many of these cases the best approach is not through the courts or the Department of Justice. Intelligence agency heads should be urged to make fuller use of their administrative authorities to suspend or dismiss employees or to lift clearances—actions with a lower threshold than criminal prosecutions but whose promptness, frequency and certainty could still deter many unauthorized disclosures.

Finally, we should (belatedly) admit that there is some common ground here. Intelligence agencies often act on the edges of executive prerogative and move forward based on a narrow base of lawfulness and limited congressional notification—and these are often sufficient to underpin a one-off covert action.

But democracies don’t get to do anything repeatedly over a long period (like drone strikes and targeted killings) without political support—and political support is the end point of a process that begins with informed debate. Informed debate depends on information, the kind that most journalists seek.

We cannot make public the nation’s legitimate secrets, but Americans need a broad outline of what is being done on their behalf. Ironically, the public dialogue generated by a free press may be one of the best guarantors that the Republic will, in the future, be able to act boldly (and occasionally secretly) in its own defense.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Michael V. Hayden.