Editor’s Note: Fadi Hakura is the associate fellow and manager of the Turkey Project at the London-based think-tank Chatham House. He has written and lectured extensively on Turkey’s political, economic and foreign policy and the relationship between the European Union and Turkey.

Story highlights

Nationwide anti-government protests are largest in Turkey in decade

Police crackdown on peaceful protests against plans to demolish park sparked riots

Protests spread from Istanbul to 67 of 81 of Turkey's provinces

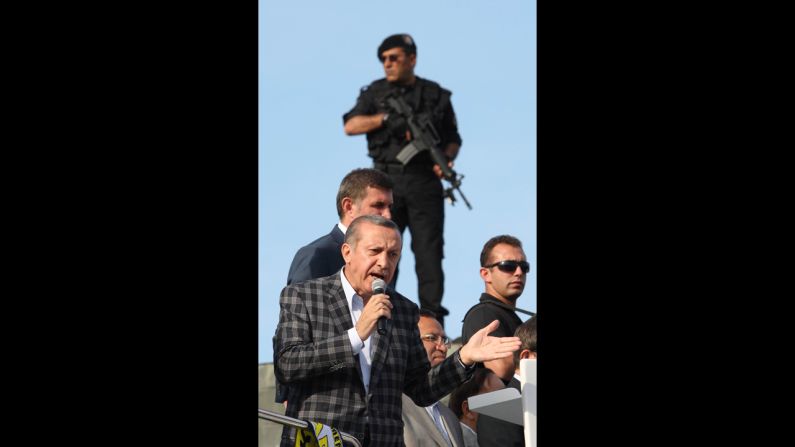

Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan calls crackdown 'excessive' but says he's not a dictator

Taksim Square is Istanbul’s equivalent to Cairo’s Tahrir Square or London’s Trafalgar Square and it is now the epicenter of demonstrations triggered by construction plans for a shopping center in one of the city’s few remaining green spaces.

What was initially a small sit-in has morphed into a major series of protests due to – in the words of Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan – “excessive force” by the police.

LATEST: Thousands of protesters tear-gassed in Ankara

These protests reflect, in part, the deep ideological polarization between secular, liberal-minded Turks, and the more religious Turks, representing a quarter and two-thirds of the population respectively based on the 2011 general election results.

Many secular Turks complainthat the Islamist-rooted government is intolerant of criticism and the diversity of lifestyles. So far, Erdogan’s robust and muscular stance vis-à-vis the demonstrators has reinforced those perceptions.

A typical example cited by detractors is the government’s recent enactment of tight restrictions on the sale and promotion of alcohol even though the Turkish government’s Household Budget Surveys estimates that only 6 percent of Turkish households are alcohol drinkers. Less than 1.5 percent of car accidents in 2012 were alcohol-related according to Turkish economist Emre Deliveli .

Despite economic boom, Erdogan targeted by protests

At the same time, critics are unhappy at the rapid pace of urbanization in Turkey’s metropolitan cities. Erdogan is planning to build a third airport, a third Bosphorus bridge and a canal linking the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara, which are likely to destroy millions of trees and a delicate ecosystem in northern Istanbul. A staggering $4.7 billion was spent on ambitious construction projects last year in Istanbul alone.

Given the litany of grievances and the confrontational nature of Turkish politics, the raging protests come as no surprise. They coincide with a rapidly slowing economy that is likely to witness moderate growth rates at best for the foreseeable future without increased structural reforms. Unfortunately, the Turkish government is not expected to undertake major reform initiatives anytime soon, especially since the campaigning for the local and presidential elections in 2014 and the parliamentary elections in 2015 are already underway.

MORE: War-torn Syria issues Turkey travel warning

Despite the rising emotions sweeping Turkey, this is not equivalent to the “Arab Spring” that led to the toppling of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak. Unlike Egypt and other Arab countries, Turkey is a functioning, albeit incomplete, democracy and has been since 1950.

Erdogan received a resounding mandate of almost half the vote in the last general elections in 2011. He still remains the most popular politician in Turkey, while the opposition is widely seen by many Turks as weak and ineffective.

Undoubtedly, the global media coverage of the riots and the disproportionate security response has dented the international image of Erdogan and the governing Justice and Development Party as a progressive force in Turkey’s political scene. Nevertheless, the ultimate determinant of Erdogan’s staying power will be the state of the Turkish economy rather than anti-government demonstrations.

What’s driving unrest and protests in Turkey?

The opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of Fadi Hakura.