Story highlights

In a 5-4 decision, the high court likens taking a DNA sample to fingerprinting an arrestee

In dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia says the ruling establishes a "terrifying principle"

Civil liberties groups worry about errors by overwhelmed lab technicians

The Supreme Court has ruled criminal suspects can be subjected to a police DNA test after arrest – before trial and conviction – a privacy-versus-public-safety dispute that could have wide-reaching implications in the rapidly evolving technology surrounding criminal procedure.

At issue in the ruling Monday was whether taking genetic samples from someone held without a warrant in criminal custody for “a serious offense” is an unconstitutional “search.”

A 5-4 majority of the court concluded it is legitimate, and upheld a state law.

“When officers make an arrest supported by probable cause to hold for a serious offense and they bring the suspect to the station to be detained in custody, taking and analyzing a cheek swab of the arrestee’s DNA is, like fingerprinting and photographing, a legitimate police booking procedure that is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment,” the majority wrote.

Law enforcement lauds genetic testing’s potential as the “gold standard” of reliable evidence gathering, especially to solve “cold cases” involving violent offenders.

But privacy rights groups counter the state’s “trust us” promise not to abuse the technology does not ease their concerns that someone’s biological makeup could soon be applied for a variety of non-criminal purposes.

Twenty-six states and the federal government allow genetic swabs to be taken after a felony arrest and without a warrant.

Each has different procedures, but in all cases, only a profile is created. About 13 individual markers out of some 3 billion are isolated from a suspect’s DNA. That selective information does not reveal the full genetic makeup of a person and, officials stress, nothing is shared with any other public or private party, including any medical diagnostics.

The Obama administration has signaled its support.

Read a summary of major upcoming decisions

The case involves a Maryland man convicted of a 2003 rape in Wicomico County in the state’s Eastern Shore region. Alonzo King Jr. had been arrested four years ago on an unrelated assault charge, and a biological sample was automatically obtained at that time. That sample was linked to the earlier sexual assault.

King moved to suppress that evidence on Fourth Amendment grounds, but was ultimately convicted of the 2003 first-degree rape offense and was given a life sentence. The Fourth Amendment grants the “right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.”

Both King and his legal team turned down CNN’s request for an interview.

A divided Maryland Court of Appeals later agreed with King, saying suspects under arrest enjoy a higher level of privacy than a convicted felon, outweighing the state’s law enforcement interests. That court also said obtaining King’s DNA immediately after arrest was not necessary in identifying him, and that the process was more personally invasive than standard fingerprinting.

But the high court decided in favor of the state. Kennedy was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, and Justices Clarence Thomas, Stephen Breyer, and Samuel Alito.

The issue of citizen privacy has been particularly acute since the 9/11 attacks. Federal and state governments have stepped up surveillance of suspected terrorists and their allies and of high-risk targets, like government buildings and shopping malls.

The current conservative-majority court has generally been supportive of law enforcement in recent search and privacy disputes, but not always. The court last year ruled police could not place a GPS tracking device on a drug suspect’s car for several weeks without first obtaining a search warrant.

In a sharply worded dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia said the majority’s reasoning established a “terrifying principle.”

“The court’s opinion barely mentions the crucial fact about this case: the search here was entirely suspicionless. The police had no reason to believe King’s DNA would link him to any crime.”

Scalia added the state law “manages to burden uniquely the sole group for whom the Fourth Amendment’s protections ought to be most jealously guarded: people who are innocent of the state’s accusations,” describing of the legal concept of innocent until proven guilty.

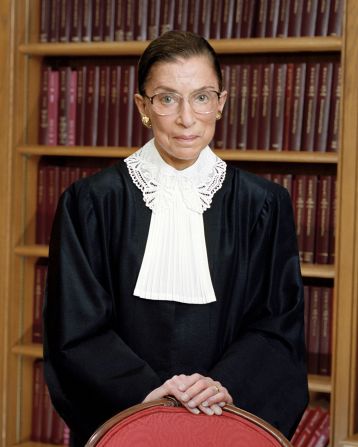

He was supported by Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan. Scalia’s prior support of Fourth Amendment protections is well-documented, so his siding with three more liberal members of the court was not surprising.

A 1994 federal law created a national database in which local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies can compare and share information on DNA matches from convicted felons, but courts have been at odds on just when such samples can be collected and the information distributed.

In a brief filed by 49 states supporting Maryland, officials also said the information is secure, and retested when an initial “hit” is identified. After a warrant is issued for probable cause, another fresh DNA sample is taken and it is that test that is used to ultimately prosecute in court. Each initial test costs about $30.

The Fourth Amendment requires the government to balance legitimate law enforcement interests with the privacy rights of individuals. A key area of concern in the high court was whether developing “Rapid DNA” technology would allow initial identification testing to be completed within about two hours. Currently it can take two weeks or more, depending on backlogs.

Civil liberties groups worry inadequate testing by overwhelmed lab technicians can lead to errors, such as the one that sent Dwayne Jackson to prison for armed robbery. It was three years before a lab mistake was noticed, and the Nevada man was freed as an innocent man.

DNA – Deoxyribonucleic acid – is a coded molecule providing a genetic map for the development of all known living organisms. By 2000, all 50 states and the federal government required DNA collection from convicted offenders, and that was soon expanded by many jurisdiction to criminal arrests.

The number of offender profiles in federal Combined DNA Index System is now about 10 million, with more than a million arrestee profiles.

Congress in December passed the Katie Sepich Enhanced DNA Collection Act, a grant program to help states pay for the expanded system. The 22-year-old woman was murdered in 2003, but her killer was not identified until three years later, after his conviction for another crime, when his DNA matched cold-case evidence found under the victim’s fingernails.

Her mother, Jayann Sepich, personally lobbied lawmakers for months to ensure passage.

President Obama signed the bill earlier this year. “It’s the right thing to do,” he said in 2010, of expanding DNA swabs for arrestees. “This is where the national registry becomes so important.”

The case is Maryland v. King (12-207).

Scenarios, terminology key in prepping for same-sex court ruling