Editor’s Note: Frida Ghitis is a world affairs columnist for The Miami Herald and World Politics Review. A former CNN producer and correspondent, she is the author of “The End of Revolution: A Changing World in the Age of Live Television.” Follow her on Twitter: @FridaGColumns.

Story highlights

Frida Ghitis: Dennis Rodman's plea on Kenneth Bae reminds us of Americans held abroad

She says a number of U.S. citizens are languishing in prisons as geopolitical pawns

She says they're held on trumped-up, dubious charges in Cuba, Iran and beyond

Ghitis: We must let families take lead on reaction but be ready to raise voice for captives' return

The drama of an American woman who unexpectedly found herself in a Mexican prison has just had a happy ending. But the plight of many other U.S. citizens kept against their will in foreign prisons continues, as anxious relatives desperately seek for a way to gain their release,

Yanira Maldonado’s sudden arrest on by Mexican authorities – who alleged she was transporting drugs, a charge she and her family vehemently denied – sparked a national outcry. It helped her case that Mexico has good relations with the U.S. Other captives, by contrast, have become the victims of complicated political and diplomatic battles between the U.S. and its foes.

Today, there are a number of American citizens languishing in prisons, some of them off the map, their survival at the mercy of powerful players with intricate agendas of geopolitical blackmail. For their families, the ordeal is emotionally devastating and becomes incalculably complicated as they try to figure out whose advice they can trust, how to avoid saying the wrong thing and how best to proceed to gain their loved ones’ freedom.

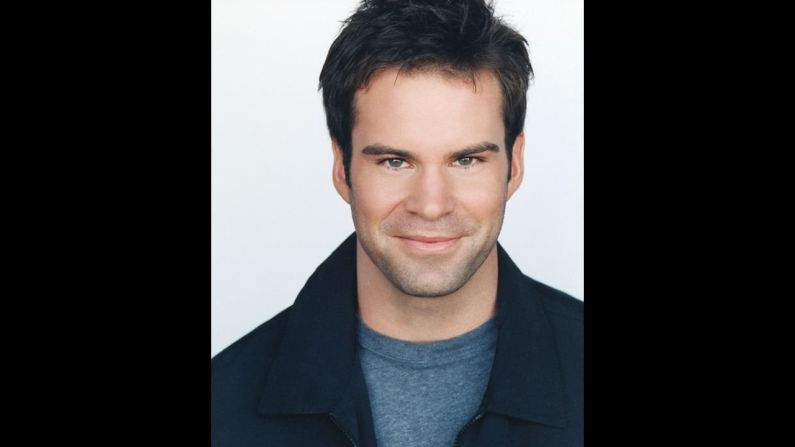

Kenneth Bae, the Korean-American owner of a tour company, was just sentenced to 15 years of hard labor, convicted for “hostile acts” against North Korea. His sister, Terri Chung, said he was in North Korea as part of his job. “We just pray” she said, asking “leaders of both nations to please, just see him as one man, caught in between.”

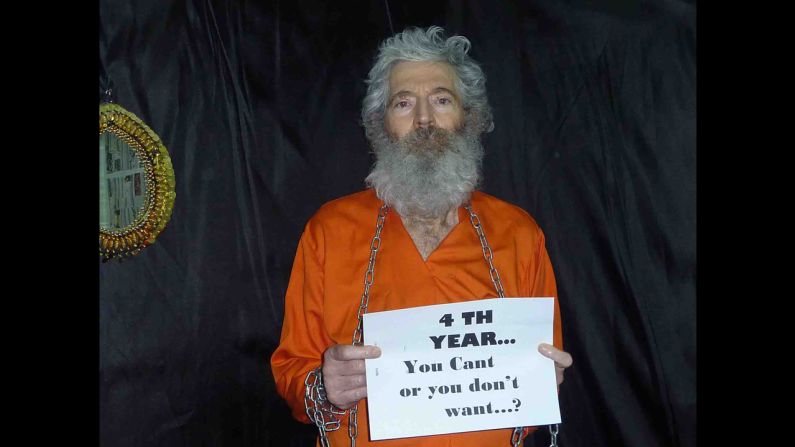

If Chung has reason for concern seeing her brother in the hands of a regime with little international accountability, the family of Robert Levinson, who disappeared in Iran six years ago, is not even sure who is holding him.

Levinson, a retired FBI agent, was working as a private investigator on a cigarette smuggling case when he traveled to the Iranian resort island Kish in March 2007. Almost immediately, he vanished.

With tensions running high between Washington and Tehran, the U.S. government believed Iranian intelligence took him as a potential bargaining chip. But Iran denies knowing his whereabouts. For years, there were no signs of life; many thought he’d died. Then more than three years after his kidnapping, the family received a wrenching video of the emaciated father of seven, his voice breaking, asking the U.S. government to acquiesce to his captors’ demands: “Please help me get home.”

His wife and son posted their own video, describing Levinson as a loving father and grandfather, begging his captors, “Please tell us what you want.”

Six years after the kidnapping, Secretary of State John Kerry called on Iran and other international partners to help, even though during a 2011 congressional hearing, Sen. Bill Nelson said, “We think he is being held by the government of Iran in a secret prison.”

Another American, Alan Gross, was arrested by Cuba in 2009 while working as a subcontractor for the U.S. government, bringing equipment to allow Internet access to members of Cuba’s Jewish community. Diplomatic cables from WikiLeaks show the arrest came during times of heightened tensions between Havana and Washington.

Havana accused him of working for U.S. intelligence. He was convicted of “acts against the independence and integrity of the state” and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

A Cuban Foreign Ministry official explained that “(t)o demand that Cuba unilaterally release Mr. Alan Gross is not realistic.” Clearly, Gross was a trading commodity. Havana wants to exchange him for five Cuban agents convicted in Miami in 2001, one of them in connection with an incident that ended in the deaths of four Cuban-Americans pilots shot down by the Cuban military.

The United States rejects the idea. Kerry declared that “Alan Gross is wrongly imprisoned, and we’re not going to trade as if it’s a spy for a spy.”

Gross’ family says Washington is not doing enough to help. The family has sued the contractor he worked for and the State Department, charging they sent him on his job without proper preparation, training or protection.

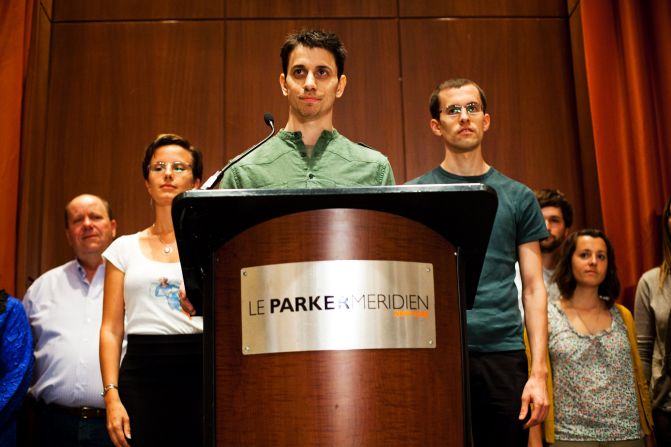

It’s difficult for families to know how much to rely on the government’s help and how much to reveal to the public. The family of James Foley, a freelance journalist captured in Syria in November, initially requested a blackout on the news.

The fear is that raising a captive’s profile can make him seem more valuable to his captors and harder to free. That is a risk, especially in a kidnapping for ransom by nonstate groups.

But GlobalPost, Foley’s employer, now says it is convinced that Foley was taken by the Syrian government’s Shabiha militia and is being held by Bashar al-Assad’s forces.

Also in government hands now is a California filmmaker, Timothy Tracy, arrested by Venezuelan authorities. His family says he was making a documentary about Venezuelan politics. The government says he was instigating unrest against the government of President Nicolas Maduro.

President Barack Obama, during his recent visit to Latin America, called the accusations, “ridiculous.”

When a government is involved, a number of possible avenues of release emerge. In fact, the release can be used as a sign of respect for humanitarian norms or of good will, aimed at easing diplomatic tensions without losing face.

These and other family ordeals continue, with little public attention focused on the struggle of people held against their will, pawns in a game in which they wield no influence.

For those wanting to help, the best approach is to listen to families’ wishes. If they want silence, that should be respected. Otherwise, we should all Tweet, post, write and talk more loudly about the ordeals of Americans held prisoner for political reasons.

Follow us on Twitter @CNNOpinion.

Join us on Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Frida Ghitis.