Editor’s Note: Andrew Salmon is a South Korea-based freelance journalist and author who has written two books on the Korean war. Below, he envisages a hypothetical, worst-case scenario of potential conflict on the Korean peninsula. CNN is not suggesting that war is imminent or even likely, but the possibility of conflict is one scenario that military strategists must consider given recent heightened tensions.

Story highlights

Fears grow on Korean peninsula of conflict after North Korean threats

Analysts say outbreak of military war between two Koreas unlikely

Impact of conflict would be devastating, even without the "nuclear option"

North Korea has more than one million troops and world's largest special forces

It’s Asia’s nightmare scenario: War breaking out on the Korean peninsula.

With Korea lying at the heart of Northeast Asia, the world’s third largest zone of economic activity after Western Europe and North America, experts say global capital markets would suffer devastating collateral damage, but the catastrophic loss of human life – and potential nuclear fallout – would be far, far worse.

iReport: Have your say about the North Korean crisis

Fortunately, no analysts believe “Korean War II” is imminent; the armistice ending the 1950-53 conflict that buried millions continues to hold, despite North Korea’s nullification in March. And with regime maintenance Pyongyang’s paramount policy, few think it would risk an attack.

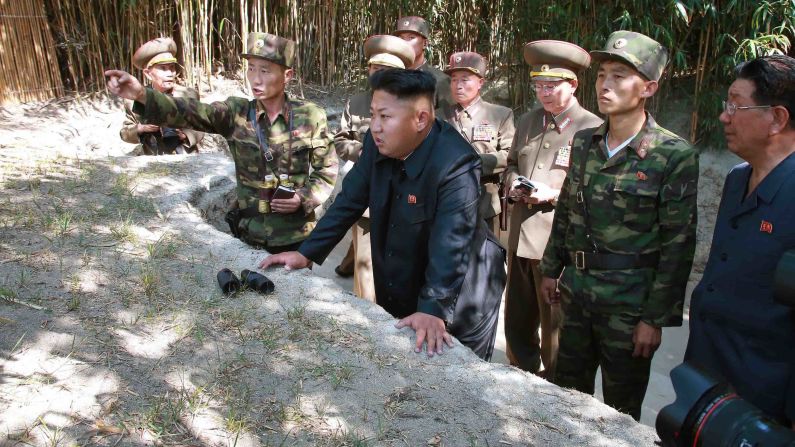

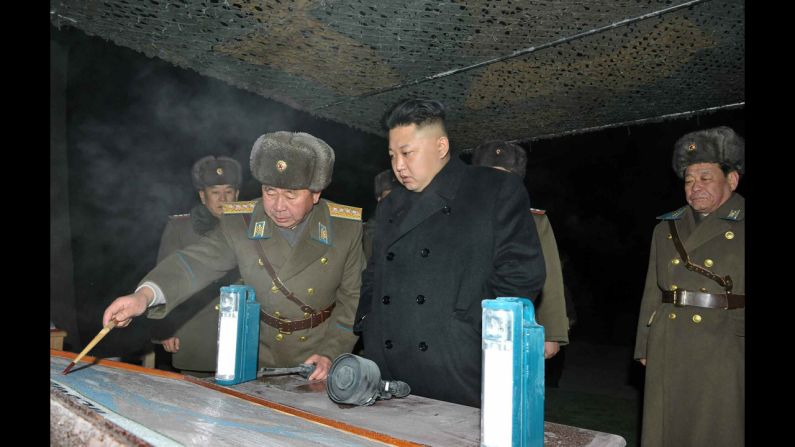

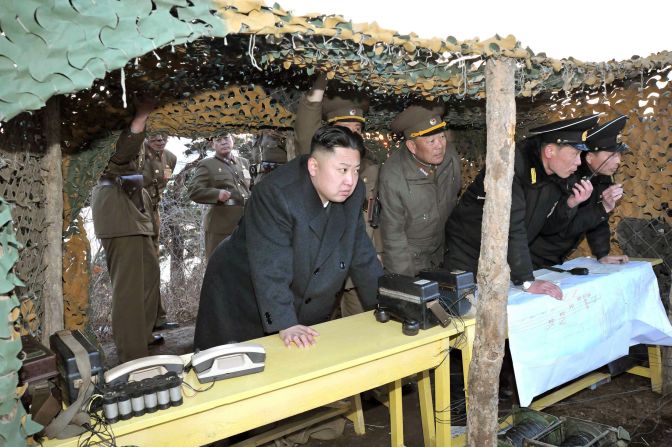

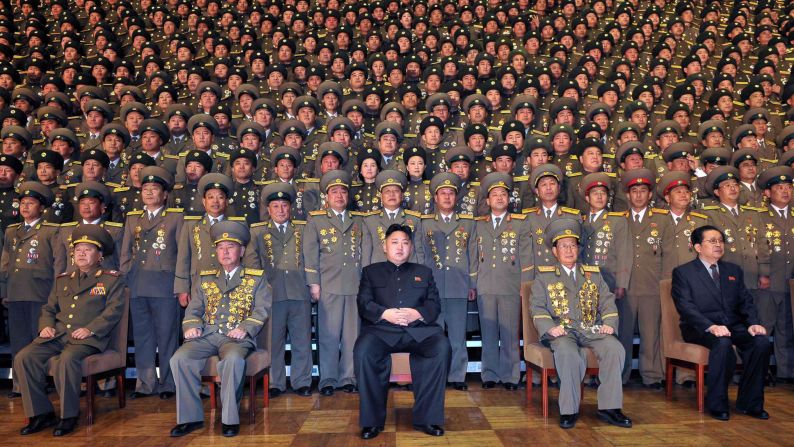

But Kim Jong Un’s experience and rationality is being questioned following his recent missile and nuclear tests, his annulment of the armistice and his bellicose vitriol – extreme even by Pyongyang standards.

Read more: What’s in a threat? North Korea’s escalating rhetoric

Despite annulling the armistice, a consistent Pyongyang demand has been a full peace treaty and it also wants direct talks with the United States, which Washington has resisted, preferring insteadmultilateral discussions.

Agreement with U.S.

Now, North Korea’s actions are fueling concern; so much so that South Korea and the U.S. recently announced they had signed an agreement to firm up contingency plans should North Korea follow through on its threats.

It follows joint military exercises between the allies, which included flights by U.S. B-52 bombers over South Korea.

At the time, Pentagon spokesman George Little said the flights were to ensure the combined forces were “battle-trained and trained to employ air power to deter aggression.”

Military strategists are clearly preparing for all eventualities. And it seems the South’s citizens are also bracing for possible conflict.

The Asan Institute, a Seoul think tank, found that in 2012, ordinary South Koreans of all age groups believed war was more likely than not.

North Korea: Cutting off military hotline with South Korea

‘Invasion unlikely’

At present, a second 1950-style North Korean invasion seems unlikely, but possibilities that could ignite the peninsula tinderbox exist.

“I don’t think any parties want all-out war, but scenarios to arrive at that outcome are some kind of miscalculation or inadvertent escalation,” said Dan Pinkston, who heads the International Crisis Group’s Seoul office. “The problem is that, considering recent developments, the escalation ladder has been getting shorter.”

After fatal incidents in 2010, South Korea eased its rules of engagement, enabling speedier counter attacks to Northern attacks such as naval or artillery strikes.

Read more: S. Korea rejects North’s calls for inquiry into sinking

And in February, South Korea’s top general told Seoul’s National Assembly of plans for pre-emptive strikes if intelligence indicated North Korean nuclear attack preparations.

Pre-emption is critical, given the close proximity of the two Koreas.

“Once we detect long range artillery and missiles being prepared, we would have no choice but to strike,” said Kim Byung-ki a professor at Seoul’s Korea University; it takes only three minutes for a North Korean plane to reach Seoul, and under a minute for artillery shells to hit.

America committed

Analysts fear a limited Northern attack might provoke a Southern response, sparking a spiral of escalation and the dreaded “big war.” With Seoul and Washington bound by treaty, America would have to commit. “Politically, the U.S. would have to be seen to support South Korea,” said James Hardy, Asia Editor at defense publication IHS Jane’s. “If it did not, its defense policy in Asia-Pacific would be in tatters.”

Read more: South Koreans mull nuclear weapons

North Korea’s 1.1 million strong Korean People’s Army, or KPA, is nearly double the size of the 640,000-person South Korean military and the 28,000 U.S. troops stationed in Korea.

Much of North Korea’s military is believed to be decrepit: It lacks fuel, fields outdated equipment, and some troops are undernourished, but it wields two niche threats: special forces and artillery.

In a report in March last year, the commander of U.S. and U.N. forces in South Korea, General James Thurman, warned that North Korea has continued to improve the capabilities of the world’s largest special operations force – highly trained specialists in unconventional, high-risk missions.

Pyongyang fields 60,000 special forces, according to Gen. Thurman – and more than 13,000 artillery pieces, most of it deeply dug in along the DMZ, and ranged on Seoul; the dense capital sprawls just 30 miles (48 kilometers) south of the border.

Moreover, with its main-force numbers and weight of firepower, the KPA might be able to concentrate offensive units with enough mass to punch across the fortified DMZ, through South Korean second echelon defenses, and barrel toward the Seoul region, an area with 24 million people.

Still, given the KPA’s logistic weakness and inability to sustain battlefield operations, analysts expect an offensive lasting only three days to one week, after which Pyongyang could negotiate from a position of strength.

Commando force

Meanwhile, could South Korean forces hold long enough for U.S. troops to massively reinforce? Could U.S. forces operate effectively with their bases in Korea – and possibly Japan, Okinawa and Guam– under attack by KPA commandos and missiles? These are the imponderables.

Commandos would provide the KPA’s spearhead, infiltrating by air, sea and probably under civilian cover to assault South Korean infrastructure and U.S. bases, degrading Seoul’s command and communications capabilities and stemming U.S. reinforcements, said Kim of Korea University. Chaos would likely be increased by electronic jamming measures and cyber attacks. Meanwhile, KPA artillery could fire thousands of shells in their opening barrage, Kim estimated.

Still, questions hang over the KPA’s war-worthiness. During Pyongyang parades, goose-stepping battalions display the world’s finest close-order drill, but under U.S. aerial bombardment, might Kim’s legions – like Saddam Hussein’s – crack?

Read more: Is Kim more dangerous than his father?

It seems unlikely. When North Korean troops have engaged – notably in Yellow Sea clashes in 1999, 2002 and 2010, and in commando raids in 1968 and 1996 – they have proven skilled and motivated.

But neither special forces nor artillery are war winners alone: They cannot seize and hold ground. The KPA’s biggest weakness is the vulnerability of its main force units once they begin to maneuver.

Aerial bombardment

The U.S. and South Korea could fight a three-dimensional battle: KPA infantry and armored units would be pummeled by 24-7 U.S. aerial bombardment; its forces would also be vulnerable to heli-borne envelopment; and, because Korea is a peninsula, the North could be flanked by sea in amphibious operations.

Still, if the KPA ran the 30-mile gauntlet from the border and broke into Seoul, a city vaster than Stalingrad, it would be easy to cut off but difficult to evict. Close combat among Korea’s hills and streets could prove murderous.

“They’re not Saddam’s army, they’re likely to fight like the Japanese in the Pacific,” said Pinkston, referring to Japan’s last-ditch island stands of 1944-5. “They would be paranoid about what would happen if they surrendered.”

Destroying North Korean artillery shelling Seoul – much of it emplaced in tunnels that have been dug over decades – would be another stern task. Kim noted that U.S. “bunker buster” bombs used in Iraq were originally designed for use against North Korea.

Seoul and Washington possess precision-guided munitions. Bombs or missiles bursting in bunker entrances could bury KPA artillery and air force units, analysts say. But the South Korean capital would likely take a severe pounding – possibly with unconventional weapons.

Bio hazard

Last March, Thurman said: “If North Korea employs biological weapons, it could use highly pathogenic agents such as anthrax or the plague. In the densely populated urban terrain of the ROK, this represents a tremendous psychological weapon.”

A marine or airborne landing to its rear are options to take out North Korea’s gun line; the question is how much damage Seoul would suffer before such operations could be launched. KPA missiles are an additional threat: As coalition forces discovered in Gulf War I, finding and destroying mobile launchers is tremendously difficult.

Yet with U.S. air power constantly degrading KPA units, communications, headquarters and logistics nationwide, experts see no way for Pyongyang to win a sustained war. If South Korea and the U.S. attack into the North, the wild card is Beijing, with whom Pyongyang has a mutual defense treaty.

Northern Korea guards China’s northeast: throughout history, a strategic flank. In 1950, with North Korea largely overrun by U.N. forces, Beijing intervened, saving the state from extinction. Pundits say Beijing would not support a Pyongyang offensive, but would defend her – suggesting Kim’s regime could survive a war, as his grandfather did.

“China will support North Korea, but only on North Korean territory,” said Choi Ji-wook, head North Korea researcher at Seoul’s Korea Institute of National Unification. “They will not support a North Korean army attacking South Korean territory.”

Tough stance

Washington wants a tougher Chinese stance toward North Korea, but it is unclear whether Beijing’s six-decade policy of support has altered significantly.

While supporting a vote to impose tougher sanctions on North Korea after its nuclear test, China recently criticized an announcement from the U.S. that it was beefing up defense systems along the U.S. West Coast.

“Bolstering missile defenses will only intensify antagonism, and it doesn’t help to solve the issue,” Hong Lei, a spokesman for the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, said at a regular news briefing in Beijing.

And regardless of the Chinese role, Kim Jong Un, North Korea’s young leader, possesses a doomsday option: The nuclear button.

Read more: Will China finally ‘bite’ North Korea?

Currently, Pyongyang is not believed to have a missile-mounted nuclear warhead, but it may in years to come. Experts believe the North has rockets able tohit Japan or South Korea with air, land or sea-delivered nuclear devices or dirty bombs. If Kim detonated a nuclear device, it would guarantee apocalyptic retaliation and war crimes trials for any regime survivors – but if all looked lost, that possibility stands.

“We’ve never been in a situation where a nuclear-armed country has had to make that kind of call,” mused Hardy. “If the leadership is going down like the Third Reich, this kind of last gasp action is possible,” added Pinkston.

Were the regime in Pyongyang overthrown by war, the positives would be extensive. South Korea would gain a land connection to the Eurasian continent; a strategic casus belli would evaporate; northern Korea could be rebuilt and its people ushered into the global community; and Northeast Asia could advance toward regional integration.

But given the destructiveness of modern weaponry and the dense populations of both Koreas, experts pray “Korean War II” never happens.

“The casualties in a short time would be unlike anything we have seen before: hundreds of thousands in days, millions in weeks,” said Pinkston. “The fighting in Iraq, Afghanistan and Syria would pale in comparison.”