Story highlights

North Korea conducted a nuclear test in February

Aggressive statements by Kim Jong Un have followed

Some analysts think the declarations are more for his own country

Video propaganda showing the White House and Congress being blown up. Talk of hitting U.S. bases in the Pacific. The renunciation of a 60-year-old armistice that has kept the tenuous peace on the Korean Peninsula.

It seems barely a day passes without another North Korean threat, and coming after the December launch of a long-range rocket and a third nuclear test in February, the florid declarations from Pyongyang have gotten the attention of the United States and its allies.

More: North Korea touts its human rights credentials

So why now, and how nervous should you be? Here are five things to consider.

It’s an inside game ..

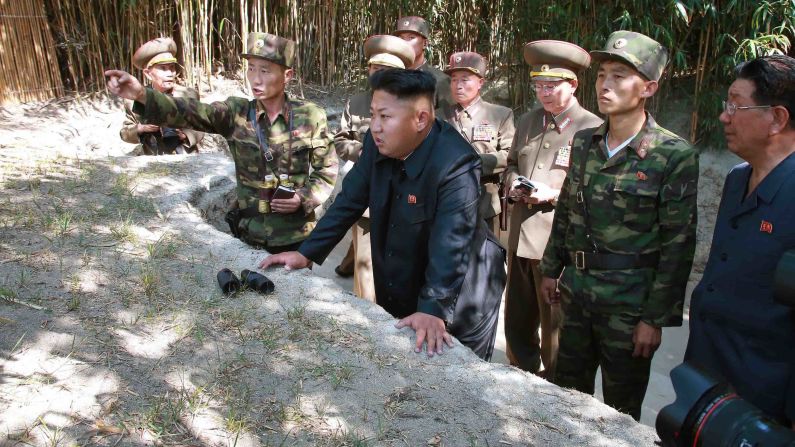

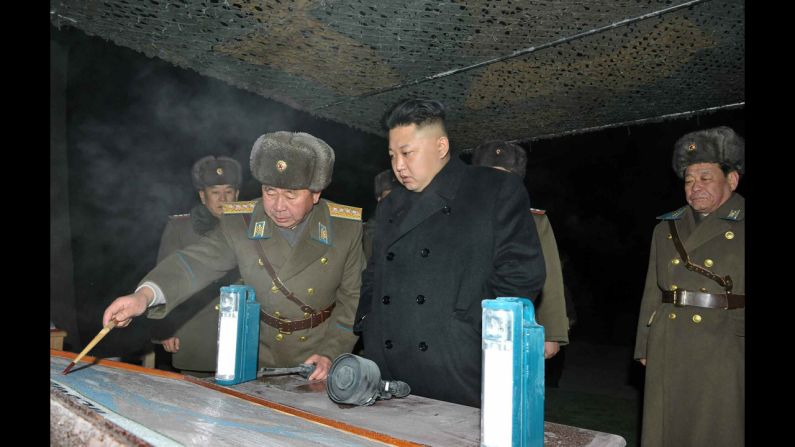

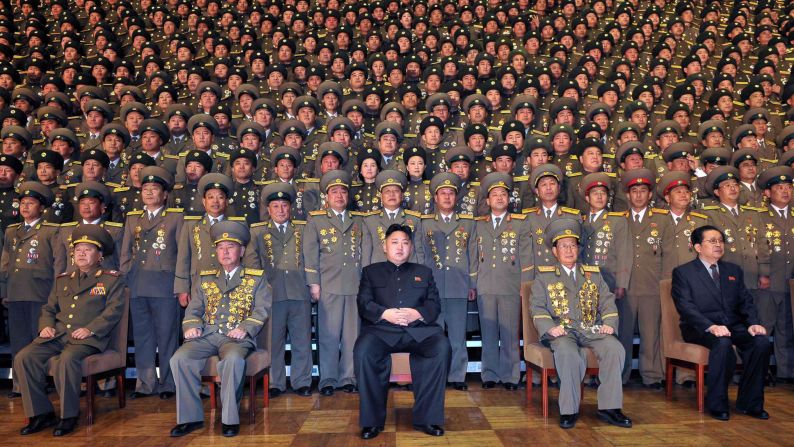

Numerous analysts on both sides of the Pacific attribute the aggressive posture is part of an attempt by North Korea’s young leader Kim Jong Un to consolidate his power in the reclusive communist state founded by his grandfather.

“First and foremost, it’s for his domestic audience,” said Jasper Kim, founder of the Asia-Pacific Global Research Group in Seoul, South Korea. “Because without the support of the military, he won’t be around for much longer. And so he has to bolster his support with the brass.”

That’s a tough sell for North Korea, “where age matters,” he added. Kim is believed to be 29.

Peter Hayes, director of the San Francisco-based Nautilus Institute, says there’s also a debate going on inside the North Korean leadership about the country’s future as a nuclear state.

One side wants “to be a nuclear-armed state that is able to behave like the recognized, legal nuclear weapons states and play their game and turn the tables on them,” Hayes said.

“That is, in my view, what is going on in the test and the rocket firing,” he said. “The other policy current is associated with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the international faction of the Korean Worker’s Party, which is to negotiate our way out of this mess.”

A recent statement from the foreign ministry declared that North Korea would not give up its nuclear “sacred sword” as long as the United States remains hostile – a conditional statement that signals Pyongyang may be willing to give up the bomb under the right circumstances, Hayes said.

Analysis: What’s Kim Jong Un up to?

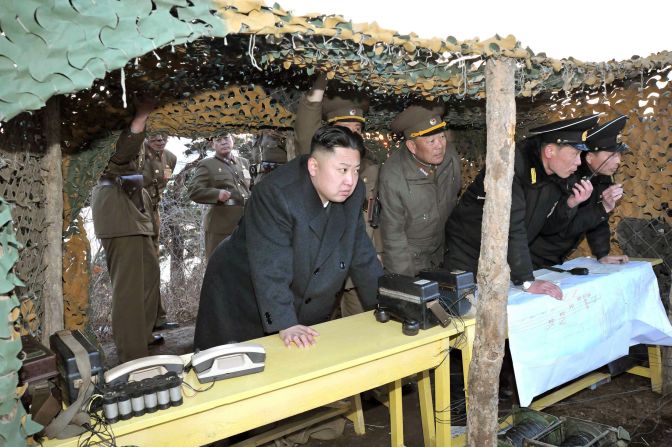

But the talk is bigger this time

“They say a lot of these kind of things, so there’s a tendency to treat it as the kind of stream of crazy you get from North Korea,” said Jeffrey Lewis, East Asia director at the California-based James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. “But this is not normal. It is more vitriolic.”

A recent statement by a top North Korean general specifically talked of hitting Washington with a nuclear weapon in the event of war. “That’s a pretty direct threat,” Lewis said.

More: Timeline of North Korea’s threats

The North Korean rhetoric ramped up after the February 12 nuclear test and the U.N. sanctions that followed. Meanwhile, Victor Cha, director of Asian Studies at Georgetown University and former director for Asian affairs at the National Security Council, told CNN’s “Fareed Zakaria GPS” that North Korea has carried out some sort of military provocation within 14 weeks of every South Korean presidential inauguration since 1992. South Korean President Park Geun-hye took office on February 25, “so start the clock,” he said.

“What is not normal is that the backdrop for this is about a year of very unpredictable behavior by a new leadership, and a sequence of provocations that is more concentrated over a period of time than we have seen in the last 20 years,” he said. “So in that context, although to the average listener these threats may seem like it’s just the North Koreans firing their mouths off again, for those of us that look at this more closely this is a little bit different – and more concerning.”

Their nukes aren’t useful … yet

Most observers say Pyongyang is still years away from having the technology to deliver a nuclear warhead on a missile. While its scientists managed to lob a small satellite into space in December, putting a working device atop a missile, launching it and hitting a target with it is vastly more complicated, Hayes said.

More: Nuclear weapons: Who has what

But Lewis, who also runs the Arms Control Wonk blog, said the North Koreans may have tried to “skip a step” with its early bomb tests and build one small enough to fit on a missile. That might explain why its first two were relatively unsuccessful.

“I think it’s plausible to think that they have a warhead design in which they are confident that’s under 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) – still not as small as you need to put on a missile and launch it to the U.S., but closer than they were a couple of years ago,” he said.

And while Washington hasn’t come out and said it, Lewis said the March 15 announcement that the Pentagon will deploy additional ground-based missile interceptors on the West Coast may signal that the North Koreans have deployed a long-range missile they put on display at a parade in 2012. Lewis said the announcement was “mostly for show,” but could reflect real U.S. concerns about those missiles.

“If you’re going to spend $1 billion to deploy interceptors, they ought to come right out and say it,” he said.

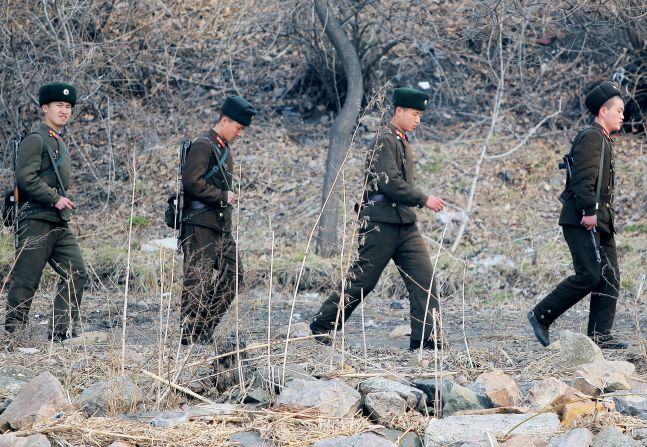

But nukes aren’t everything

North Korea also has plenty of conventional military firepower, including medium-range ballistic missiles that can carry high explosives for hundreds of miles, as well as thousands of cannons, rocket launchers and tanks massed across the Demilitarized Zone that separates North and South. Seoul is within range of many of those weapons, and the North has threatened before to turn the southern capital into a “sea of fire.”

A North Korean bombardment could kill tens of thousands of people in Seoul before South Korean and U.S. retaliation could smash those guns, Hayes said. But that would essentially launch a new Korean War – one he said would end badly for the long-impoverished North.

“They have less than 30 days of fuel and no ability to refuel,” he said. “They’ve got to fight a very short war before they’re just walking to where they’re going to fight.”

Pyongyang keeps its forces massed on the DMZ “precisely because they’re weak,” he said.

There are other avenues. When computers at South Korean banks and broadcasters began to crash on Wednesday, suspicion initially fell on the North. South Korea has accused the North of similar hacking attacks before, including incidents in 2010 and 2012 that also targeted banks and media organizations. Adam Segal, a cybersecurity expert with the Council on Foreign Relations, said the hacking is consistent with previous North Korean actions.

Threats of annihilation normal for South Koreans

So now what?

For years, Pyongyang has made deals to curtail its nuclear and missile work in exchange for economic aid. Those deals have fallen apart when the North went on to conduct other tests. The six-party talks among the North, its Asian neighbors and the United States fizzled in 2007, and the North’s first attempt at a satellite launch scotched a previous U.S. plan to trade hundreds of thousands of tons of food for a halt to weapons work.

“I think the problem right now is that you cannot engage them directly after they have done a series of ballistic missile and nuclear tests, and we are going into a period of sanctions now through the U.N. Security Council resolution,” Cha said.

“They don’t want to give up their nuclear weapons. They want to be able to have their cake and eat it, too. And U.S. policy for the past quarter-century has been these things are all on the table if you are willing to give up your nuclear weapons,” he said. “And so this is the problem. This is the dilemma right now.”

Meanwhile, the United States is going ahead with joint U.S.-South Korean military exercises amid the North Korean threats, adding a special little twist – overflights by massive B-52 bombers. It’s a move reminiscent of the worst days of the Cold War, and one Hayes called “tactically smart but strategically stupid.”

“The North Koreans will have noted it for what it is – an affirmation of the fact that we’re playing the nuclear game with North Korea, and that’s the last thing we want to do,” he said. “I think our posture is either to persuade ourselves that we’re hanging tough, which is a domestic game in Washington, or to reassure our allies and dissuade South Korea from going it alone with nuclear weapons.”

But both Hayes and Lewis said there’s little to lose by continuing to engage the North.

“We do what we can on defense, and if the North Koreans want to bargain or haggle, I’m prepared to do that,” Lewis said.

READ MORE: 5 ways North Korea is getting stranger

READ MORE: Angry over U.N. inquiry, North Korea touts its human rights credentials

READ MORE: North Korea warns that U.S. bases in Guam, Japan are within range

READ MORE: North Korea declares 1953 armistice invalid

CNN Correspondent Matthew Chance contributed to this report.