Story highlights

"We just don't know the stability of their leader," Rep. Mike Rogers says

Rogers is chairman of the House Intelligence Committee

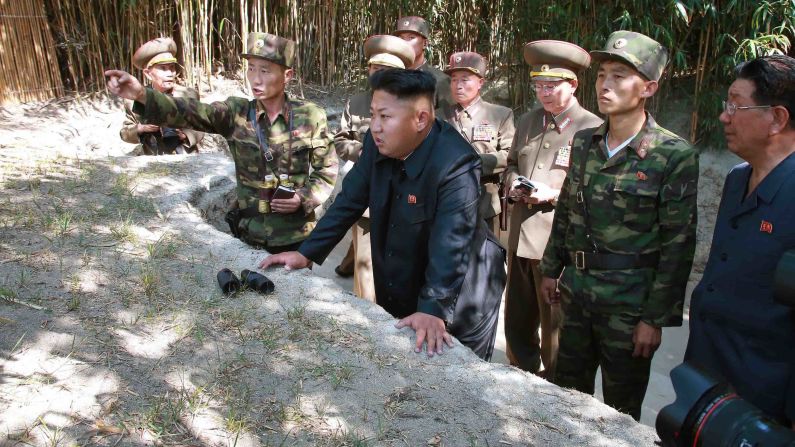

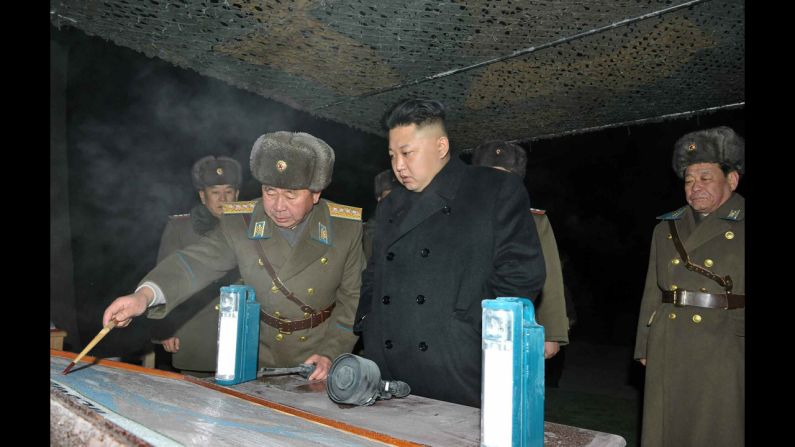

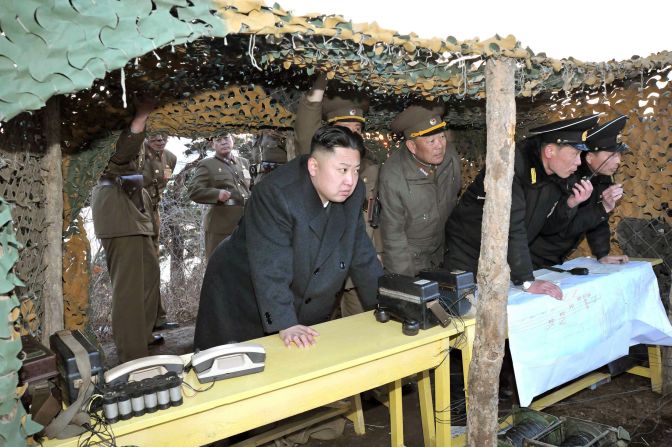

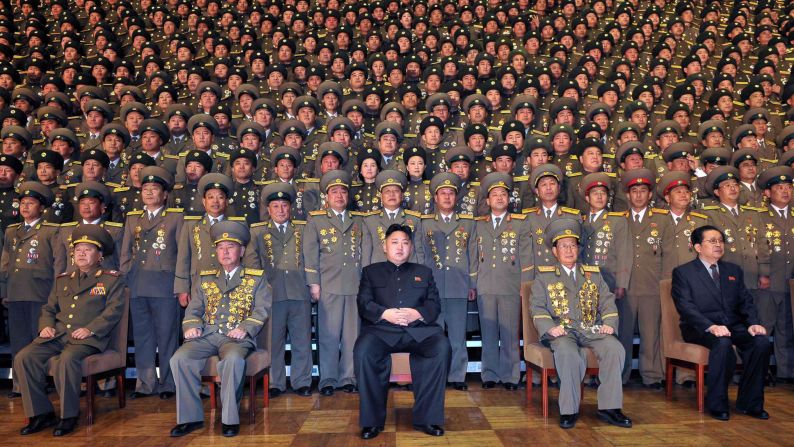

Analysts debate whether Kim or the North Korean military is really in charge

A top U.S. congressman expressed concern about the “stability” of North Korean leader Kim Jong Un after months of provocative statements and behavior from the nuclear-armed communist state.

“You have a 28-year-old leader who is trying to prove himself to the military, and the military is eager to have a saber-rattling for their own self-interest,” said Rep. Mike Rogers, the chairman of the House Intelligence Committee. “And the combination of that is proving to be very, very deadly.”

North Korea launched a satellite into orbit atop a long-range rocket in December, conducted its third nuclear weapons test in February and announced earlier this month that it was abandoning the 1953 armistice that ended the Korean War.

On Saturday, it announced that it would not negotiate with the United States over its nuclear program, challenging arguments that its weapons program was a bargaining chip that might be traded away for economic benefits.

READ: North Korea: Nuclear program not a bargaining chip

Rogers, R-Michigan, told CNN’s State of the Union that North Korea “certainly” has the missile capability to strike the United States. Analysts say North Korea is years away from being able to accurately deliver a nuclear weapon atop a long-range missile. But Rogers said the fact that the North is willing to openly threaten the United States with a nuclear attack “is problem enough.”

“This is very, very concerning, as we just don’t know the stability of their leader – again, 28 years old,” Rogers said. “We’re just not confident that we know he wouldn’t take those steps.”

Pyongyang disregarded numerous warnings to conduct February’s test and threatened afterward that it was prepared to launch a pre-emptive nuclear strike to defend itself. The U.N. Security Council stiffened sanctions on the North after the test, with its leading ally, China, making the vote unanimous.

The North has also renewed its threats toward South Korea, warning of “strong physical countermeasures” after the sanctions vote.

READ: U.S. to beef up missile defenses

Kim is the grandson of Kim Il Sung, the founder of the North Korean state. He rose to power in December 2011, after the death of his father, Kim Jong Il. Victor Cha, a longtime North Korea analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, said the North’s recent actions have fueled debate about whether Kim “really is fully in charge, or whether the military is in charge.”

“The three top military generals that were with him when his father died are all gone now, and we don’t know what happened to them,” Cha said on CNN’s Fareed Zakaria GPS.

“That could be a sign of him taking control, but it could also be a sign of some real churn inside the system where some people don’t like the fact that a 28-year-old is now running the country.”

And Donald Gregg, a former adviser to then-Vice President George H.W. Bush and former U.S. ambassador to South Korea, said North Korean contacts he has met recently told him “that they have given up on their diplomats, and the military is now in control.”

“What they want is to talk about moving from the now-disbanded armistice agreement to the creation of a peace treaty,” Gregg told GPS. “That’s what they want to talk about, and anyone who is willing to talk about that, they will listen to. Anyone who wants to talk about what they call the old way, which was give up your nuclear weapons and then we’ll talk, is going to get nowhere.”

Gregg recommended engaging the North Koreans in new talks. But Cha, a former National Security Council official in the second George W. Bush administration, said that can’t be done so soon after their nuclear and missile tests, and he predicted “a very difficult period for the next couple of months or so.”

“They don’t want to give up their nuclear weapons. They want to be able to have their cake and eat it, too,” he said. “U.S. policy for the past quarter century or so has been, ‘These things are all on the table if you’re willing to give up your nuclear weapons.’ This is the problem. This is the dilemma right now.”