Story highlights

Center-left Democratic Party leader Pier Luigi Bersani, 61, expected to win election

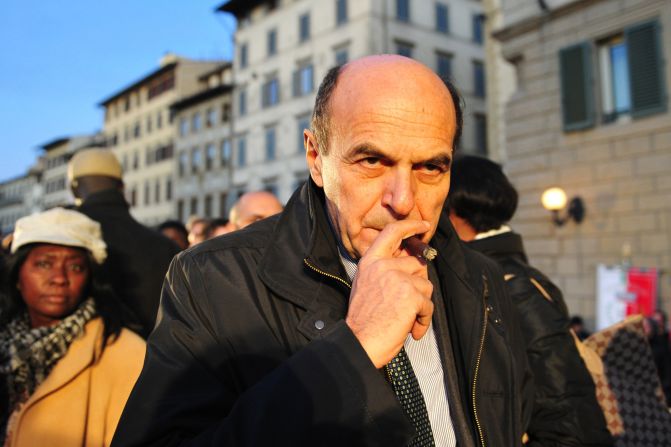

Cigar-smoking ex-communist has spent career in politics, served in three cabinets

Bersani said he'd continue Monti's budget cuts, but that stimulus is needed too

After years of turbulent ex-premier Berlusconi, Bersani is seen as pair of safe hands

The man expected to become Italy’s next prime minister won’t pound the bully pulpit like Silvio Berlusconi. He won’t claim to be the Jesus Christ of politics, or praise Barack Obama’s “tan”, and it’s highly unlikely you’ll bump into him at an all-night bunga bunga party.

No, Pier Luigi Bersani is seen as a safe pair of hands – and now, after a lifetime in politics, the 61-year-old leader of the center-left Democratic Party is hoping to hang on to a lead in the polls that bombastic three-time former premier Berlusconi had all but wiped out in the dying days of the campaign.

A cigar-puffing ex-communist and pillar of the Italian left, Bersani campaigned on the promise of “A Just Italy” – but as he knows, it will take far more than words to fix Europe’s fourth-largest economy.

Italy in crisis

From top to bottom, Italy is a mess. Berlusconi, its last elected prime minister, quit in disgrace in 2011 and is now on trial for allegedly paying for sex with an underage girl. Italy has the third highest debt-to-GDP ratio in the first world, and only Haiti and Zimbabwe grew less from 2000 to 2010.

Italy ranks 72nd in corruption – behind Ghana and Saudi Arabia – and at an estimated €140 billion euros in yearly turnover, organized crime is the country’s biggest industry, according to one business association report. Italy ranks a woeful 73rd in the Ease of Doing Business index, 80th in gender equality, and income equality is growing.

Mario Monti, who was appointed to run the country after Berlusconi’s departure, has forced through a bitter package of cost-cutting measures to save the country from financial ruin, snuffing out any hope of short-term growth. Italy’s economy has shrunk for a staggering six straight quarters, and its 11.2% unemployment rate is the highest since they began keeping records in 1999.

READ: Italy, from ‘La Serenissima’ to bunga bunga

And while Monti may have some say in the new Italian government, it is career politician Bersani who will bear the burden of pulling Italy out of the mire.

From school teacher to party leader

Bersani was born in Bettola, a village in northwest Italy, in 1951. The son of a mechanic, he studied philosophy and wrote his thesis on Pope Gregory I at Bologna University, according to his campaign website. The lifelong Catholic has been married to Daniela Ferrari since 1980 and has two daughters.

Bersani abandoned a brief stint as a schoolteacher in favor of local politics, joining the Communist Party in the historically left-leaning region of Emilia-Romagna.

READ: Who will win Italy’s election? What are the issues?

The Communist Party folded at the end of the Cold War but Bersani continued his way up the ranks in the leftist parties that followed, becoming the president of the Emilia-Romagna regional council in 1993.

Bersani served in cabinet for three center-left governments between 1996 and 2008, most recently as the minister of economic development, when in a break with his communist roots he embarked on a series of free market reforms aimed at making Italian industry more competitive.

Last December, voters in his Democratic Party had the opportunity to choose a younger, more vibrant politician to carry the torch for the Italian left in the upcoming election in the form of Matteo Renzi, the brash 38-year-old mayor of Florence.

But while Renzi’s following is growing, he was seen as too much of a modernizer for an Italian left long dominated by ex-communists, according to Geoff Andrews, an Open University senior lecturer and expert on Italian politics.

“Renzi is seen as a Blairite, but it’s never been a Blairite left in Italy, and I don’t think he was trusted by some of the party faithful,” Andrews told CNN.

Bersani, the popular party veteran, trounced Renzi in the primary by almost 22 points. But his nomination might also say as much about Italy’s current political climate as it does about the candidates.

“After years of Silvio Berlusconi, voters need a rest,” says Beppe Severigni, an Italian journalist who spoke to CNN during an 11-day train journey across the country to gauge voters’ moods ahead of the election.

READ: ‘Il Cavaliere’ – Italy’s most colorful public figure

“Italians are nervous, anxious and exhausted, the mood is the same everywhere. After so long on the roller coaster people want a safe pair of hands, and Bersani is banking on that.”

A more just Italy

If elected, Bersani has pledged to continue with Monti’s unpopular budget-cutting reforms and sees them as a necessary evil, but he says Europe’s strict focus on austerity measures is preventing Italy from growing.

“The rigor and credibility that Monti has brought into the world are for us a point of no return,” he told CNN, several weeks before the election. “[But] we believe that a stimulus is necessary to the European and the Italian economy.”

Bersani will also pursue civil unions for gay people, immigration reform, and €500 million worth of government-funded university scholarships, according to the Democratic Party website.

He says he will retain an unpopular property tax that his rival Berlusconi has promised to repeal, and refund, in its entirety – a promise Mario Monti called “a poison meatball,” according to The New York Times.

One of Bersani’s main goals will be to enact labor reforms to make it cheaper for businesses to hire, but experts say his allegiance to Italy’s labor unions could complicate any attempts at change.

“Italy has a lot of protected industries and interests, and Bersani has a lot of ties to CGIL, Italy’s largest labor union,” said Open University’s Geoff Andrews. “He is somebody from the old school left, and it’s unlikely he’s going to take a strong fight to the unions.”

Can Bersani govern?

According to Andrews, winning the election is just the beginning of Bersani’s problems.

Even if Bersani wins the election, recent polls have him falling well short of a majority of the vote. Most experts believe in order to govern he will need to try to cobble together a coalition with the more centrist Monti, whose austerity measures are deeply unpopular with factions of Bersani’s current alliance.

And even if Bersani and Monti manage to strike a deal, Berlusconi could get enough votes to make life difficult for the coalition once it’s in office.

His return to power may be unlikely, but the fact Berlusconi looms large in the election – just 15 months after resigning as Italy hit rock bottom – is a testament not only to his domination of Italian politics over the past 20 years, but also to the left’s inability to capitalize on his scandals, according to Andrews.

“There’s a lot of pessimism about the next government, and the problem Bersani’s got has been the failure of the left to deal with Berlusconi,” Andrews said. “They’re all sort of living in his shadow.”

Italy has had more than 60 governments since World War II, and desperately needs a stable government to nurse its battered economy back to health.

But while Bersani has sold voters on his promise of “politics that tell the truth,” the truth is that the election may only be the start of the battle for control of Italy’s future – and it’s hard to keep the man everyone calls “Il Cavaliere” down for too long.