Story highlights

Silvio Berlusconi is campaigning to win his old job back for the fourth time

The eurozone's third largest economy is hurting, with unemployment surpassing 11%

Pier Luigi Bersani of the center-left Democratic Party is expected to narrowly win

Italy's political system encourages the forming of alliances

Little more than a year after he resigned in disgrace as prime minister, Silvio Berlusconi is campaigning to win his old job back – for the fourth time.

Berlusconi, the septuagenarian playboy billionaire nicknamed “Il Cavaliere,” has been trailing in polls behind his center-left rival, Per Luigi Bersani.

But the controversial media tycoon’s rise in the polls in recent weeks, combined with widespread public disillusionment and the quirks of Italy’s complex electoral system, means that nothing about the race is a foregone conclusion.

Why have the elections been called now?

Italian parliamentarians are elected for five-year terms, with the current one due to end in April. However in December, Berlusconi’s People of Freedom Party (PdL) withdrew its support from the reformist government led by Mario Monti, saying it was pursuing policies that “were too German-centric.” Monti subsequently resigned and the parliament was dissolved.

Berlusconi – the country’s longest serving post-war leader – had resigned the prime ministerial office himself amidst a parliamentary revolt in November 2011. He left at a time of personal and national crisis, as Italy grappled with sovereign debt problems and Berlusconi faced criminal charges of tax fraud, for which he was subsequently convicted. He remains free pending an appeal. He was also embroiled in a scandal involving a young nightclub dancer - which led him to be charged with paying for sex with an underage prostitute.

MORE: From Venice to bunga bunga: Italy in coma

He was replaced by Monti, a respected economist and former European Commissioner, who was invited by Italy’s President Giorgio Napolitano to lead a cabinet of unelected technocrats. Monti’s government implemented a program of tax rises and austerity measures in an attempt to resolve Italy’s economic crisis.

Who are the candidates?

The election is a four-horse race between political coalitions led by Bersani, Berlusconi, Monti, and the anti-establishment movement led by ex-comedian Beppe Grillo. Polls are banned within two weeks of election day, but the most recent ones had Bersani holding onto a slender lead over Berlusconi, followed by Grillo in distant third.

READ MORE: Will Monte Paschi banking scandal throw open Italy’s election race?

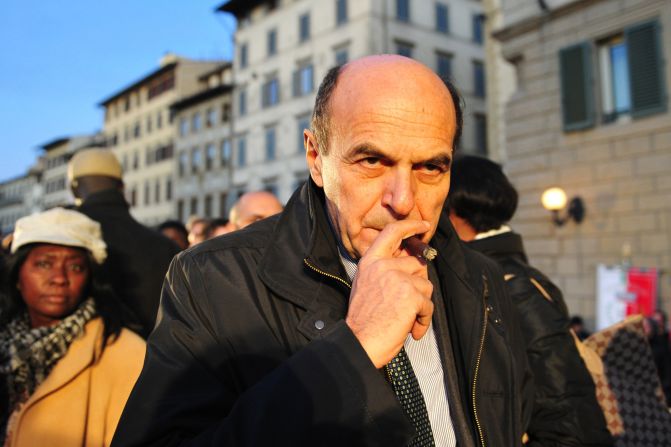

The center-left alliance is dominated by the Democratic Party, led by Bersani. He is a former Minister of Economic Development in Romano Prodi’s government from 2006-8 – and has held a comfortable lead in polls, but that appears to be gradually being eroded by Berlusconi.

Italy’s political system encourages the forming of alliances, and the Democratic Party has teamed with the more left-wing Left Ecology Freedom party.

The 61-year-old Bersani comes across as “bluff and homespun, and that’s part of his appeal – or not, depending on your point of view,” said political analyst James Walston, department chair of international relations at the American University of Rome.

He described Bersani, a former communist, as a “revised apparatchik,” saying the reform-minded socialist was paradoxically “far more of a free marketeer than even people on the right.”

Bersani has vowed to continue with Monti’s austerity measures and reforms, albeit with some adjustments, if he wins.

At second place in the polls is the center-right alliance led by Berlusconi’s PdL, in coalition with the right-wing, anti-immigration Northern League.

Berlusconi has given conflicting signals as to whether he is running for the premiership, indicating that he would seek the job if his coalition won, but contradicting that on other occasions.

In a recent speech, he proposed himself as Economy and Industry Minister, and the PdL Secretary Angelino Alfano as prime minister.

Roberto Maroni, leader of the Northern League, has said the possibility of Berlusconi becoming prime minister is explicitly ruled out by the electoral pact between the parties, but the former premier has repeatedly said he plays to win, and observers believe he is unlikely to pass up the chance to lead the country again if the opportunity presents itself.

Berlusconi has been campaigning as a Milan court weighs his appeal against a tax fraud conviction, for which he was sentenced to four years in jail last year. The verdict will be delivered after the elections; however, under the Italian legal system, he is entitled to a further appeal in a higher court. Because the case dates to July 2006, the statute of limitations will expire this year, meaning there is a good chance none of the defendants will serve any prison time.

He is also facing charges in the prostitution case (and that he tried to pull strings to get her out of jail when she was accused of theft) – and in a third case stands accused of revealing confidential court information relating to an investigation into a bank scandal in 2005.

Despite all this, he retains strong political support from his base.

“Italy is a very forgiving society, it’s partly to do with Roman Catholicism,” said Walston. “There’s sort of a ‘live and let live’ idea.”

Monti, the country’s 69-year-old technocrat prime minister, who had never been a politician before he was appointed to lead the government, has entered the fray to lead a centrist coalition committed to continuing his reforms. The alliance includes Monti’s Civic Choice for Monti, the Christian Democrats and a smaller centre-right party, Future and Freedom for Italy.

As a “senator for life,” Monti is guaranteed a seat in the senate and does not need to run for election himself, but he is hitting the hustings on behalf of his party.

In a climate of widespread public disillusionment with politics, comedian and blogger Beppe Grillo is also making gains by capturing the protest vote with his Five Star Movement. Grillo has railed against big business and the corruption of Italy’s political establishment, and holds broadly euro-skeptical and pro-environmental positions.

How will the election be conducted?

Italy has a bicameral legislature and a voting system which even many Italians say they find confusing.

Voters will be electing 315 members of the Senate, and 630 members of the Chamber of Deputies. Both houses hold the same powers, although the Senate is referred to as the upper house.

Under the country’s closed-list proportional representation system, each party submits ranked lists of its candidates, and is awarded seats according to the proportion of votes won – provided it passes a minimum threshold of support.

Seats in the Chamber of Deputies are on a national basis, while seats in the senate are allocated on a regional one.

The party with the most votes are awarded a premium of bonus seats to give them a working majority.

The prime minister needs the support of both houses to govern.

Who is likely to be the next prime minister?

On current polling, Bersani’s bloc looks the likely victor in the Chamber of Deputies. But even if he maintains his lead in polls, he could fall short of winning the Senate, because of the rules distributing seats in that house on a regional basis.

Crucial to victory in the Senate is winning the region of Lombardy, the industrial powerhouse of the north of Italy which generates a fifth of the country’s wealth and is a traditional support base for Berlusconi. Often compared to the U.S. state of Ohio for the “kingmaker” role it plays in elections, Lombardy has more Senate seats than any other region.

If no bloc succeeds in controlling both houses, the horse-trading begins in search of a broader coalition.

Walston said that a coalition government between the blocs led by Bersani and Monti seemed “almost inevitable,” barring something “peculiar” happening in the final stages of the election campaign.

Berlusconi, he predicted, would “get enough votes to cause trouble.”

What are the main issues?

There’s only really one issue on the agenda at this election.

The eurozone’s third largest economy is hurting, with unemployment surpassing 11% – and hitting 37% for young people.

Voters are weighing the question of whether to continue taking Monti’s bitter medicine of higher taxation and austerity measures, while a contentious property tax is also proving a subject of vexed debate.

Walston said the dilemma facing Italians was deciding between “who’s going to look after the country better, or who’s going to look after my pocket better.”

He said it appeared voters held far greater confidence in the ability of Monti and Bersani to fix the economy, while those swayed by appeals to their own finances may be more likely to support Berlusconi.

But he said it appeared that few undecided voters had any faith in Berlusconi’s ability to follow through on his pledges, including a recent promise to reverse the property tax.

What are the ramifications of the election for Europe and the wider world?

Improving the fortunes of the world’s eighth largest economy is in the interests of Europe, and in turn the global economy.

Italy’s woes have alarmed foreign investors. However, financial commentator Nicholas Spiro, managing director of consultancy Spiro Sovereign Strategy, says the European Central Bank’s bond-buying program has gone a long way to mitigating investors’ concerns about the instability of Italian politics.

Why is political instability so endemic to Italy?

Italy has had more than 60 governments since World War II – in large part as a by-product of a system designed to prevent the rise of another dictator.

Parties can be formed and make their way on to the political main stage with relative ease – as witnessed by the rise of Grillo’s Five Star Movement, the protest party which was formed in 2009 but in local and regional elections has even outshone Berlusoni’s party at times.

Others point to enduringly strong regional identities as part of the recipe for the country’s political fluidity.

READ MORE: Italian Elections 2013: Fame di sapere (hunger for knowledge)