Editor’s Note: Greg Bear is an internationally bestselling science-fiction author of many books, including “Moving Mars,” “Darwin’s Radio” and “Hull Zero Three.” As a freelance journalist, he covered 10 years of the Voyager missions at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Story highlights

Greg Bear: Asteroid Apophis flew by this month and was much larger than expected

Named after an evil Egyptian serpent god, Apophis swings by every seven years

Bear: We can never be 100% sure how close it will come or if events might change its course

If Apophis hit Earth, he says, the blast would be the equivalent of over a billion tons of TNT

Look up at our nearest neighbor, the moon, and you’ll see stark evidence of the dangerous neighborhood we live in. The Man in the Moon was sculpted by large-scale events, including many meteor and asteroid impacts.

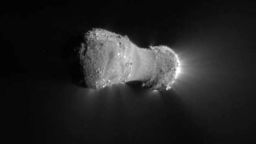

In 1994, the comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 dove into Jupiter. The result was awesome. The impact caused a brilliant flash, visible in Earth telescopes, and left an ugly dark scar on Jupiter’s cold, gaseous surface.

With the recent fly-by of a 1,000-foot-wide asteroid labeled 99942 Apophis, one of a class of space rocks referred to as “near-Earth objects” or “Earth-grazers,” scientists have revised their worst estimates of its chances of striking Earth. Current thinking is: We’re safe. For the next couple of decades.

But this does not mean the danger is over. Far from it.

Get our free weekly newsletter

Named after the evil Egyptian serpent god Apophis, lord of chaos and darkness – and recently dubbed the “doomsday asteroid” – it flies past Earth every seven years. This year, its 1,000-foot bulk approached to within 9 million miles. In 2029, it will swoop in close enough to put some of our orbiting satellites in peril – 20,000 miles. In that year, no doubt Apophis will arouse even more attention, because it will be visible in the daytime sky. In 2036, it will probably pass by at a reassuring 14 million miles.

Yet there’s always a possibility we don’t have these measurements exactly right. Something could happen at any point in Apophis’ orbit to modify its course, just a smidgen. A tiny collision with another object, way out beyond Mars? What could change between now and 2029, or during any orbit thereafter?

Apophis masses at more than 20 million tons. If it hit Earth, the impact would unleash a blast the equivalent of over a billion tons of TNT. That’s not an extinction event, but it could easily cause billions of deaths and months, if not years, of climate disruption.

The potential risk is huge. And Apophis is far from alone. Life in our solar system has always been dangerous. As kids we learn about the Barringer Crater in Arizona, a relatively recent formation – 50,000 years old – caused by a rock weighing several times more an aircraft carrier. That impact released the equivalent of 20 megatons of TNT and left a crater 4,000 feet wide.

Both Mars and Earth were long ago hit by planet-sized objects, one spinning off our Moon, the other shaping two distinctly different hemispheres on Mars. To this day, a steady rain of meteors falls on Earth – some of them left-over pebbles and dust from worn-out comets, others from the “asteroid belt,” still others from big strikes on the Moon and Mars.

Since oceans cover two-thirds of the Earth’s surface, it’s more likely debris will hit water than land. Scientists believe it was the blast of a 6-mile-wide asteroid off the coast of Mexico some 64 million years ago that changed Earth’s weather for years and hastened the departure of the dinosaurs. Ocean hits are worse than land hits, not just because of immense tidal waves, but because of the vast quantities of super-heated water vapor and dust that spread from the impact to shroud the entire Earth.

In March 1966, J.E. Enever published his ground-breaking article, “Giant Meteor Impact,” in the periodical Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact. Enever surveyed the available material on meteor and asteroid strikes, then published his own calculations and analysis of what such strikes could do, and have done, to the Earth, with cinematically vivid prose and equally terrifying physics.

He was the first to put it all together and publish in a respected and widely available forum. Although geology was still reluctant to admit to any form of “catastrophism,” eschewing biblical explanations, many read and pondered … seriously.

In the decades since Enever’s article, writers, scientists, and engineers have proposed various ways to avert such disasters. Some have suggested we strap rocket motors to a threatening rock and nudge it away. A steady pulse of projectile “paintballs” could also do the trick.

Others have suggested we use nuclear weapons to “kick” an asteroid from its orbit, or even to shatter it into smaller debris – a rather dim idea that misleads us into believing a single bullet is worse than the blast from a shotgun. Our atmosphere provides little protection against meteors larger than a truck.

Moreover, many asteroids are chunky masses of rock and dust loosely held together by very little gravity, like loosely packed peanut clusters. Attempting to attach a rocket to one of these might merely dislodge a few “peanuts,” leaving the rest to do the dirty work.

Wrap one of these peanut clusters in a giant steel net, then drag it off its deadly course? Intriguing, but for now – like deploying tractor beams from the starship Enterprise – it’s just so much super-science.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Greg Bear.