Story highlights

Researchers find a protein called tau in the brains of living retired NFL players

Its pattern is identical to that found in chronic traumatic encephalopathy cases

CTE can only be diagnosed after death

More study is needed to confirm the findings

An insidious, microscopic protein that has been found in the brain tissue of professional football players after death may now be detectable in living people by scanning their brains.

Researchers say they found tau protein in the brains of five living retired National Football League players with varying levels of cognitive and emotional problems.

“It’s definite, we found it, it’s there,” said Dr. Julian Bailes, co-director of the NorthShore Neurological Institute in Evanston, Illinois, and co-author of a new study that identified the tau. “It was there consistently and in all the right places.”

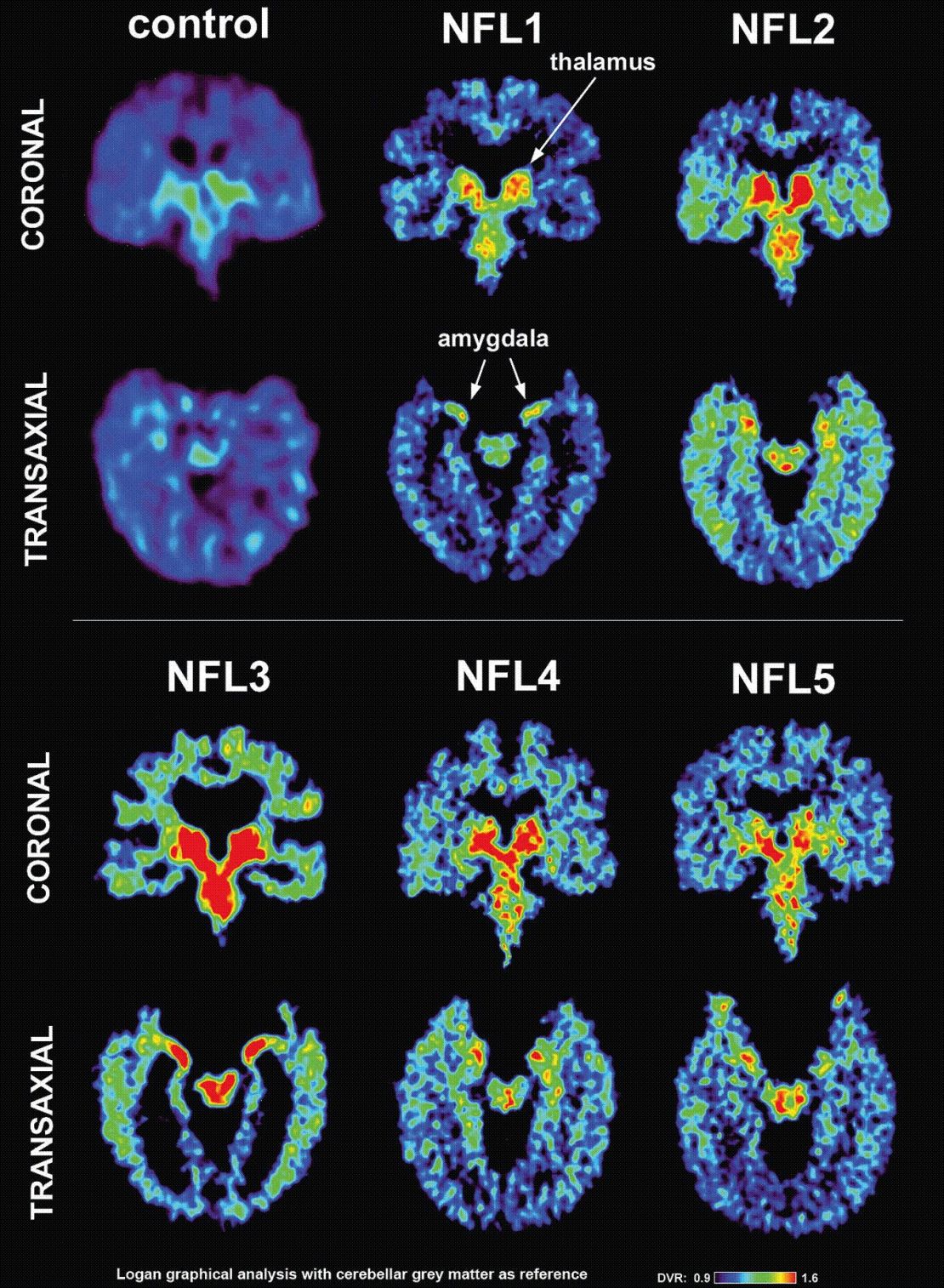

Using a scan called positron emission tomography, or PET – typically used to measure nascent Alzheimer’s disease – researchers injected the players with a radioactive marker that travels through the body, crosses the blood-brain barrier and latches on to tau.

Then, the NFL retirees had their brains scanned.

“We found (the tau) in their brains, it lit up,” said Dr. Gary Small, professor of psychiatry at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior at UCLA and lead author of the study, published Tuesday in the American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry.

What was startling, said Small, was the specific pattern of the tau they found: “It was identical to what’s seen in a condition called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, CTE, that has only been diagnosed at autopsy.”

CTE is the disease that most likely played a role in the deaths of former NFL players like Dave Duerson, Ray Easterling, Shane Dronett, and Junior Seau.

What has stymied researchers for years is that tau can only be uncovered after death. Finding it in living players is considered by many researchers to be the “holy grail” of concussion research, according to Bailes.

“After a while it gets old and not so fulfilling to take the brain out when (an athlete) is dead,” said Bailes, a neurosurgeon and director of the Brain Injury Research Institute, which focuses on the study of traumatic brain injuries and their prevention. “At that point there is no solution, no answer.”

More cases of brain disease found in football players

The research provides the beginnings of an answer, according to Bailes and Small. But the study is tiny, and poses looming questions.

“This is a very exciting but preliminary study,” said Robert Stern, co-founder of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at the Boston University School of Medicine. “The researchers did what so many of us have been wanting to do for the last couple of years.

“The problem is that the type of PET scan they used is really not specific to what we’re looking at with chronic traumatic encephalopathy.”

The marker used in the PET scan – the one that binds to tau – is called FDDNP. The problem with using that marker, said Stern, is that it is not specific enough. It binds not just to tau, but also to another protein called beta amyloid, which is commonly seen in Alzheimer’s disease patients.

“In CTE, only tau is found in abundance,” said Stern, an Alzheimer’s expert. “What researchers saw was parts of the brain lighting up and showing abnormal findings. … But we don’t know if what is lighting up is tau alone, or beta amyloid, or both.”

It’s the location of the protein that is important, Small said. In Alzheimer’s disease, tau is typically found in the outer part of the brain, called the cortex.

“It’s different from Alzheimer’s,” said Small, director of the UCLA Longevity Center, adding that he found tau in deeper structures of the brain.

“The patterns of the scans are identical to what’s seen at autopsy in other people (with CTE),” like Seau, Duerson and Easterling, he said. “And we know at autopsy it’s primarily tau.”

When tau lodges into those deep brain structures – for example, the amygdala, which is associated with rage and other emotions, or the hippocampus, a seat of memory – it causes major disruptions to those areas.

Questions linger about long-term impact of subtle hits to the head

That disruption may be related to depression, memory problems and suicidal behavior common in cases of CTE studied thus far – not just in retired NFL players, but in athletes in other sports and members of the military.

The hope among the study’s authors is that a diagnostic brain scan might one day detect burgeoning CTE in all sorts of people who suffer concussions.

But the current study is drawing some skepticism, doubts that likely will not ebb until future research examines a larger study group.

“Sometimes I wish (study authors) would hang on and wait until they have a more meaningful sample size,” said Kevin Guskiewicz, a concussion expert and director of the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “I think that then people would be less skeptical of the findings.”

Still, Guzkiewicz is encouraged by the study results.

“Unfortunately we tend to identify these (CTE) cases when they’re already on the slippery slope toward dementia and it’s too late to do anything,” said Guskiewicz. “I’m all for trying to build on studies like this.”

Building on the research – expanding the study population – is what Small and Bailes are working on now. In the meantime, they are optimistic about their findings.

“Right now, the (FDDNP) PET scan is the only method that we know of that can measure tau protein in living people,” said Small. “It’s not the perfect holy grail … but for now it seems to be showing us what we’re looking for.”

Football players more likely to develop neurodegenerative disease