Story highlights

Belmoktar has long been a target of French counter-terrorism forces

Analysts believe the attack is too sophisticated to have been planned in days

Belmoktar earns the nickname "Belaouar" -- the "one-eyed" -- after a battlefield injury

He allegedly is involved in smuggling drugs, weapon and people

The terrorist attack on a natural gas installation at In Amenas in eastern Algeria may be an isolated act of revenge for the French intervention in Mali – or an ominous portent of things to come in North Africa, where Islamist militancy is gaining traction fast.

The man claiming responsibility for the operation is a veteran jihadist who is also renowned for hostage-taking and smuggling anything from cigarettes to refugees.

Read more: Islamists take foreign hostages in attack on Algerian oil field

His name is Moktar Belmoktar, an Algerian who lost an eye while fighting in Afghanistan in his teens and has long been a target of French counter-terrorism forces.

Today, he leads a group called Al-Mulathameen Brigade (The Brigade of the Masked Ones), which is associated with al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM.) In the last few years, he has cultivated allies and established cells far and wide across the region.

Read more: Power struggle: The North African gas industry targeted by militants

Assault on In Amenas

The gas complex where Belmoktar’s followers struck at dawn Wednesday is in a region that has seen plenty of jihadist activity in recent years, in part because of the collapse of government authority across the Libyan border, just 50 kilometers (31 miles) from In Amenas.

Counter-terrorism experts differ as to how the attackers - in several pickup trucks - may have reached In Amenas, but there are several roads and tracks across uninhabited desert from Libya. On the other side of the border, a patchwork of militia prevails rather than any government presence.

A spokesman for Al-Mulathameen told Mauritanian news websites that the attack was in retaliation for Algeria permitting French overflights as part of the intervention in Mali. But regional analysts believe it was too sophisticated to have been planned in days.

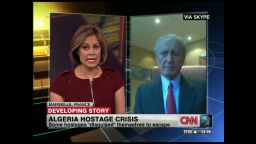

Robert Fowler, a former Canadian diplomat who was abducted by Belmoktar’s followers in Niger in 2008 – and met the man himself – told CNN, “I suspect they have an intelligence wing and they are constantly looking for ways to grab westerners and embarrass the West and confuse our options. And that’s exactly what they are doing.”

Read more: Fallout from Mali battle goes global after militants seize Westerners in Algeria

In a 28-minute video that appeared on jihadist forums last month, Belmoktar warned that Al-Mulathameen would soon act against Western interests in the region.

“This is a promise from us that we will fight you in the midst of your countries and we will attack your interests,” he said.

Announcing the formation of an elite commando unit called “Those Who Sign With Blood,” Belmoktar said it would be the shield against the “invading enemy.”

Wednesday’s attack in Algeria was claimed in the name of that unit, which Belmoktar said would include “the best of our youth and mujahideen, foreign and local supporters.”

Counter-terrorism analysts tell CNN the language suggests this group was dispatched to carry out an act of jihad rather than abduct foreigners for ransom.

Watch: Islamist militants attack oil field, two dead

“This feels much more like attacks staged in the past by other al Qaeda affiliates, rather than another attempt to exchange hostages for ransom, as has often been AQIM’s practice,” said Andrew Lebovich, a long-time observer of AQIM currently in Senegal.

“Belmokhtar likely wants to show he is still engaged in active operations and he is not moving away from the fighting - especially at a time when other Jihadists are in active combat against French troops in Mali,” he said.

But it is also possible that Belmoktar may try to bargain for the release of al Qaeda operatives held in Algerian jails.

In his December message, he said, “To our captive people…it is our promise and our debt as long as we live that we will liberate you, and we sacrifice our lives for you and everything we own to free you.”

Three al Qaeda operatives were detained last July by Algerian security services, but it’s not known whether they were close to Belmoktar.

Read more: Six reasons events in Mali matter

Marlboro Man

Born in 1972, Belmoktar grew up on the edge of the desert in southern Algeria.

He traveled to Afghanistan in 1991 in his late teens to fight its then Communist government. He returned to Algeria as a hardened fighter with a new nickname “Belaouar” – the “one-eyed” – after a battlefield injury, and joined forces with the Armed Islamic Group (GIA) in its brutal campaign against the Algerian regime and civilians deemed to be its supporters.

Belmoktar later claimed he met al Qaeda founder Osama bin Laden in the Sudan in the mid 1990s.

According to Jean-Pierre Filiu, a French scholar who has extensively studied AQIM, Belmoktar rose steadily through the ranks to become the GIA commander for the Sahara.

After a popular backlash against the terrorist group in Algeria, Belmoktar switched allegiance to a spin-off group – the GSPC – in 2000, and continued to operate in the sub-Saharan region.

The GIA was the forerunner of AQIM, which still counts many Algerians in its leadership. Belmoktar remains associated with this fissiparous group – but is very much his own man.

Abdelmalik Drukdal, the overall leader of AQIM, is said to have demoted Belmoktar late last year from his position as ‘Emir of the Sahel.’ Belmoktar also feuded with a rival commander - Abou Zeid - one of the most violent and radical figures in AQIM. More than most al Qaeda affiliates, AQIM is divided into often competing groups.

Citing regional security officials, Agence France Presse reported Belmoktar had been dismissed for “continued divisive activities, despite several warnings.”

Libyan sources tell CNN that Belmokhtar spent several months in Libya in 2011, exploring cooperation with local jihadist groups, and securing weapons supplies.

One Arab media report - cited in a US Federal Research Division report last year - said Belmoktar had attended an event organized by Wissam ben Hamid, an Islamist commander, in the town of Sirte. There is no way to verify that.

More recently, his center of operations was the dusty town of Gao in northern Mali.

Another offshoot of AQIM known as the Movement for Unity and Jihad has taken over Gao and introduced Sharia law, including public amputations and floggings.

To make money, “Belmoktar increasingly engaged in smuggling, earning the popular nickname ‘Mr. Marlboro’ … he also was involved in the smuggling of drugs, weapons, and illegal immigrants,” Jean-Pierre Filiu in a 2010 Carnegie Paper.

A wide theater

Criminality helped fund jihad.

In December 2007, Belmoktar’s followers murdered four French tourists in MaurItania. Two months later, they carried out a drive-by shooting on the Israeli Embassy in Nouakchott, Mauritania’s capital.

“We set an ambush to kill the ambassador of the Zionist entity in Mauritania before attacking the compound that housed the embassy and the nightclub that the ambassador was present in minutes before the attack,” Belmoktar told a Mauritanian journalist in November 2011.

Despite US satellite surveillance and the deployment of Algerian and MaurItanian troops to vulnerable areas, al Qaeda affiliates in the Sahel have grown in strength.

The vast distances and empty landscapes - as well as a complex relationship with local tribes - play to their advantage. Borders are difficult to seal: the rugged Algerian-Malian frontier is as long as the distance from New York to Chicago.

In February 2012, a cache of SAM missiles - looted from Libyan armories - was discovered buried in the desert not far from In Amenas.

Andrew Lebovich says the weapons - SA-7 nd SA-24 “seem to have been at a midway point in the delivery process,” their destination and customer unknown.

Many AQIM figures - Belmoktar and Abou Zeid included - know the region minutely.

Indeed, Lebovich says some suspect that it was relatives of Abou Zeid who kidnapped a local Algerian official a year ago - bundling him across the border into Libya.

In the view of one Libyan source with close contacts among the region’s jihadists, Belmoktar has often been a thorn in the side of AQIM’s leadership.

“He was seen as a loose canon, running things in his own way,” the source told CNN recently. “and the last thing the leadership wanted was to antagonize the United States just when it was trying to build up strength by stealth, below the radar.”

However the hostage stand-off is resolved, that strategy has now been blown to pieces.