Story highlights

Richard Ben Cramer, author of monumental "What It Takes," dead at 62

Cramer remembered as generous, warm, a little stubborn

"What It Takes" called one of the great books on American politics in 20th century

Cramer's other books included biography of Joe DiMaggio, thoughts on Mideast

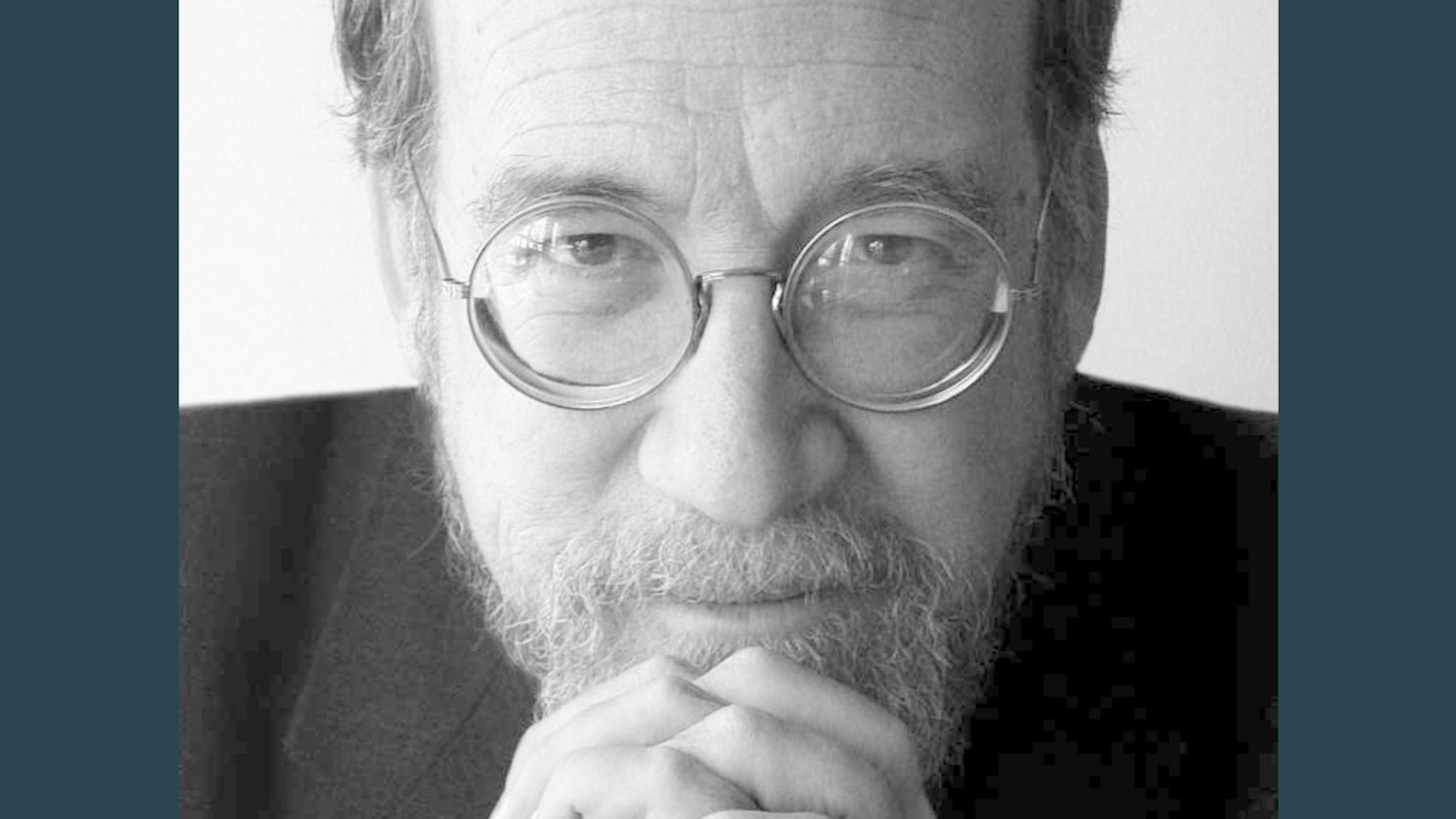

Richard Ben Cramer, the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer whose 1992 book “What It Takes” remains one of the most detailed and passionate of all presidential campaign chronicles, died Monday night, according to his longtime agent, Philippa “Flip” Brophy. He was 62.

The cause of death was lung cancer.

Cramer’s work – and work ethic – was legendary among reporters. He talked in firm, declamatory bursts in a growl of a voice tinged with cigars and alcohol. He was generous with other writers, dogged in his pursuit of information, and known for idiosyncratically “doing things in his own way, on his own schedule,” recalled Brophy.

“He was stubborn, charming and the most brilliant person I knew – and the warmest,” she said.

“He was an unmatched talent who set an enormously high bar for political journalism. I will miss him,” said Vice President Joe Biden in a statement. Biden and Cramer became friendly when the author was working on “What It Takes.”

CNN senior political analyst Gloria Borger, echoing many, attests to his generosity. She was a cub reporter for the old Washington Star when she was assigned to the Maryland statehouse beat. Cramer, then with The (Baltimore) Sun, took her under his wing.

“I was this new kid on the block, and he’d been around and knew Maryland politics very well, and he was smart and a brilliant writer – and kind to a new reporter on the beat,” she said.

Cramer put all his fury, emotion and eye for detail on the page in such works as “Joe DiMaggio: A Hero’s Life” (2000), “How Israel Lost” (2004) and especially “What It Takes,” a 1,047-page account of the 1988 presidential race.

“What It Takes” reads like Tom Wolfe on speed, like Theodore H. White left out in the wild. It’s fueled by Cramer’s determination to find out just exactly why people are crazy enough to run the obstacle course in pursuit of the nation’s highest office.

The book contains astute and sympathetic profiles of George H.W. Bush, Michael Dukakis, Joe Biden and particularly Bob Dole. The latter comes across as particularly rich, with his distinctive third-person speaking style and tossed-off “Aghs,” all rendered with Cramer’s painterly eye.

“Too much political journalism today, even in book form, is geared more toward staff feuds and soap opera and less to what Richard spent so much time in 1988 exploring: what makes these candidates tick, and what drives them to compete in such an arduous – and yes, at times, ridiculous process,” said CNN’s chief national correspondent, John King, who covered the Dukakis campaign that year.

Cramer plunged into the day-to-day drudgery of a presidential campaign with a vengeance, and what emerges is half winged exultation, half death march. (Indeed, the strain of doing the book made him very ill, though reports that it nearly killed him were “exaggerations,” said Brophy.) In the long history of campaign works, which includes White’s “Making of the President” series, Hunter S. Thompson’s “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72” and John Heilemann and Mark Helperin’s gossipy “Game Change,” Cramer’s tome looms large – “one of the most important books on American politics in the 20th century,” said Michael Pakenham, a former editor at the Philadelphia Inquirer and a Cramer colleague.

The book was hugely influential. “Richard Ben Cramer transformed a whole generation of political reporters with his sweeping chronicle of the 1988 campaign,” said Howard Kurtz, host of CNN’s “Reliable Sources” and Washington bureau chief for The Daily Beast. “While almost no one could write and report as he did, he set the bar higher for everyone.”

Cramer was fascinated as much by the machinery that produced power and hero worship as he was by the people at their center. “He was a journalist who listened and watched particularly well,” says Butch Ward, a senior faculty member at the Poynter Institute and another former Inquirer colleague. “He went places most of us aspired to, but he got there.”

Such determination didn’t often sit well with reviewers. “What It Takes” was criticized as self-indulgent; “How Israel Lost,” which painted a bleak picture of Cramer’s former Mideast stomping grounds, was knocked as simple-minded. And Cramer’s warts-and-all DiMaggio biography, though a bestseller, was slammed for the author’s blunt handling of the New York Yankee hero.

Cramer “relentlessly, pulverizingly tells us that the man wasn’t worthy of the legend built up around him,” Allen Barra wrote in Salon. The review was headlined “Joe Cruel.”

Cramer, of course, didn’t see it that way.

“I think among older fans there’s a sense that I’m somehow messing with their own memories, which was never my intent,” he told CNN at the time. “I can understand their annoyance. But to me the life of DiMaggio was always more interesting than the myth.”

Cramer was born in Rochester, New York, in 1950, and studied at Johns Hopkins and Columbia’s journalism school. He worked at The Sun in the 1970s and then at the Philadelphia Inquirer from 1977 to 1984. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his Middle East reporting in 1979.

As a freelance writer, he wrote a number of well-received profiles, including a Rolling Stone piece on Jerry Lee Lewis, an Esquire cover story on Baltimore mayor (and later Maryland governor) William Donald Schaefer, and a much-talked-about story on Ted Williams, later reprinted as the book “What Do You Think of Ted Williams Now?”

Despite his renown among journalists, he wasn’t always an easy sell, recalls Brophy. After she signed him – “intercepting” him from agency head Sterling Lord because she loved his newspaper and magazine work – she spent years funneling him book ideas from interested publishers. “He’d say, ‘No, no, no, no, no,’ and I would say (to others), ‘He’s really the type of person who needs to come up with his own idea.’ “

When he finally had his own idea, it was for “What It Takes,” a mammoth undertaking that frightened publishers. “I said, ‘Richard, that’s a great book idea, but it’s not a first book. It’s like a 10th book.’ And he went, ‘Sell it,’ ” said Brophy. “And I did.”

With just four books and a handful of magazine articles over his long post-newspaper career, Cramer operated on his own clock. Sometimes that meant literally, said Brophy. One morning, while researching “What It Takes,” he called her at 7:30, saying that he had missed a 7:15 flight. “What time did you get there?” she asked.

“7:20,” he replied.

But that was Cramer, agree his friends, an occasionally shambling presence who was also a keen observer, a raconteur, a baseball fan, a master of ceremonies. (He served the latter role at Pakenham’s wedding.) Ward imagines him in another time, another place, holding court with some other witty friends.

“It’s probably not too much a stretch to imagine Richard sitting at the Algonquin, sharing great thoughts with other people,” he said.

Cramer is survived by his wife, Joan Cramer, and a daughter, Ruby. An earlier marriage ended in divorce. According to The Sun, there will be no funeral at Cramer’s request.