Editor’s Note: Michael Halpern works with the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists. He is an expert on the use of science in government policy and writes on the intersection of science and politics at The Equation. Follow him on Twitter @MichaelUCS.

Story highlights

Michael Halpern: We need scientific research on gun violence to inform policy

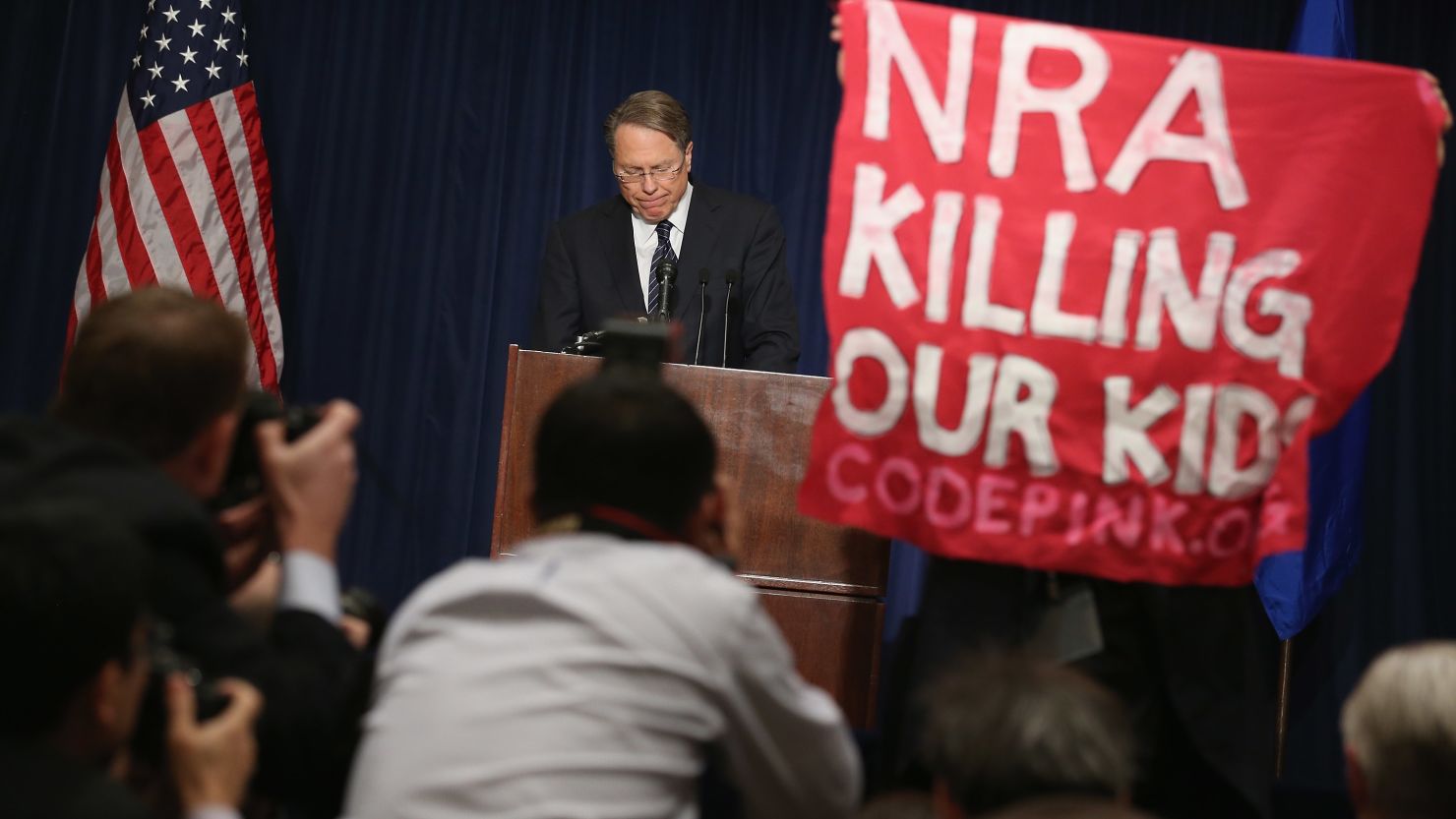

Halpern: The NRA pressured Congress to end gun violence research at CDC

Researchers free from conflicts of interest should work with policy makers, he says

Also, we must open our minds to findings that disagree with our beliefs, he writes

Since the December 14 mass killing in Connecticut, we’ve seen a lot of finger pointing. Too many guns. Not enough guns. Powerful lobbyists. Insufficient mental health services.

Discussion of possible explanations is often neither civil nor constructive, and based on a closed-minded and entrenched belief that those who disagree with us have their facts wrong.

The victims in Sandy Hook, Aurora and Fort Hood – all killed or wounded by gun violence – deserve better.

There are two major ways we can zero in on facts and foster a more informed discussion.

The first is to further develop and meaningfully consider high quality scientific research on violence prevention and mental health. The second is to create more opportunities for public policy discussions that incorporate this research.

Politics: New Congress, new push for gun laws

The scientific literature regarding violence prevention is considerable. Yet important research that focuses on gun violence has been shut down for political purposes. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention once considered gun violence a public health issue. The science agency had the freedom to ask important questions: Does having a gun in the home make a family safer? Do concealed carry laws increase or reduce gun fatalities?

Get our free weekly newsletter

But in 1996, the National Rifle Association pressured its many supporters in Congress to put the squeeze on the CDC by cutting funding that went to gun research, with the stipulation: “None of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.” Gun-related research ground to a halt.

In 2009, scientists funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism looked into whether carrying a gun increases or decreases the risk of being shot in an assault. In 2011, Montana Rep. Denny Rehberg inserted a provision into a funding bill that extended the CDC restrictions to the rest of the Department of Health and Human Services, ending that similar research. Even Obamacare has been touched by the NRA: The new health care law restricts doctors’ ability to collect data about patients’ gun use.

“Criticizing research is fair game,” Drs. Arthur Kellermann and Frederick Rivara wrote in opposition in the Journal of the American Medical Association last month. “Suppressing research by targeting its sources of funding is not.”

Science and engineering research can answer important questions. For instance, can we cost-effectively engineer firearms to be used solely by the registered owner? What’s the best way for law enforcement agencies to share gun violence data? Does media attention focused on the killers encourage copycat crimes? Does better access to mental health services reduce criminal activity?

Some findings could lead to policy choices that aren’t yet on the table or help determine where we should best focus our attention. Republicans and Democrats alike are warming up to the idea that adequate research can lead to more informed policy decisions. Former Rep. Jay Dickey, the Arkansas Republican who led the charge against the CDC in 1996, recently expressed regret for suppressing firearm safety research.

Just as important, how do all these pieces of the puzzle fit together? Having an informed debate means relying on credible syntheses of expert studies.

To come up with answers, scientific organizations, such as the National Academy of Sciences, could convene independent panels to piece together what is known and what is not known and to evaluate various policy options. The commission set up after the 2010 British Petroleum oil spill is one such example. The 9/11 Commission is another.

When independent experts who are free from conflicts of interest come together in good faith to study an issue, they can have a profound and constructive influence on government policy. At a more basic level, national and state legislative committees should hold more hearings designed to study evidence rather than using hearings as theater to advance a political point of view.

Nongovernmental organizations, including the one where I work, can redouble their efforts to bring scientists and policymakers together. This is especially important after the demise of the Office of Technology Assessment, a research office within Congress that, until the mid-1990s, provided independent analyses on issues up for congressional debate.

In the absence of a reliable base of information we can all agree on, we guess. We interpret the facts to suit our beliefs. We put our faith in the institutions or individuals we trust, whether it’s the NRA, religious leaders or gun control groups. And we keep on having the same broken debate.

Of course, the evidence can only take us so far. Moral, economic, legal and political arguments can and should carry weight. But robust research can set the baseline for a discussion and help us make the best decisions for society.

The more polarized, caustic and poorly analyzed an issue, the more intractable it becomes. We need to develop venues for rational discourse about research that is resilient to political pressures.

More robust partnerships among scientists, policymakers and the public can help us work together to address critical challenges, even after they fall from the headlines.

Vice President Joe Biden is leading a task force to address our country’s problem of gun violence. One critical step the task force should embrace is to lift restrictions on the research public health scientists can do. And we can all reject attempts to discredit evidence that challenges our beliefs.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter.

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Michael Halpern.