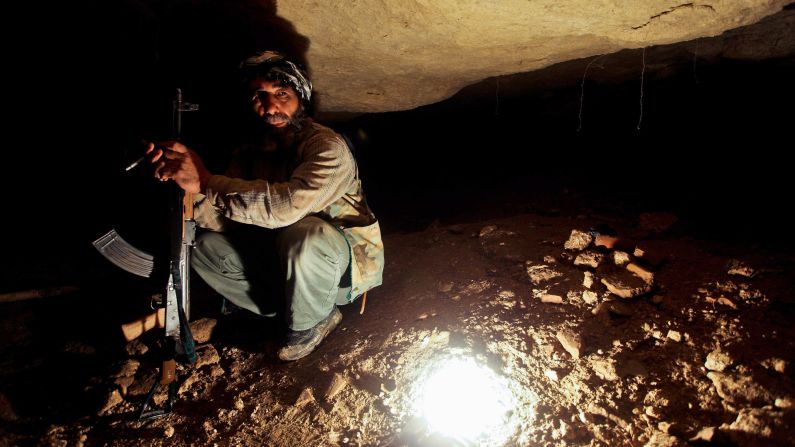

Story highlights

CNN's Nic Robertson and Nick Paton Walsh examine what the future may hold for Syria

Paton Walsh: 'Very little doubt' the rebels will defeat the regime of Bashar al-Assad

Robertson: It will take years to rebuild the country's infrastructure, economy

Syria’s civil war has been grinding on for nearly two years now, resulting in the deaths of more than 60,000 people, according to estimates from the office of the U.N. Human Rights Commissioner.

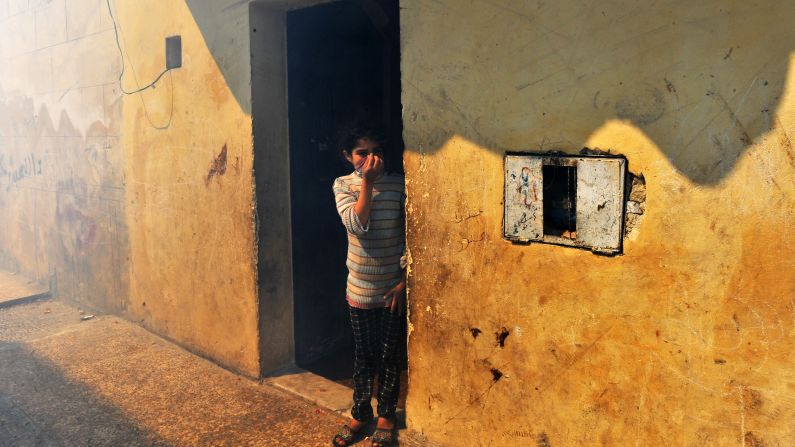

More than 500,000 Syrians have sought refuge in neighboring countries, and the U.N. believes that number could top a million in the coming year.

Will the situation improve in 2013, or will the bloody stalemate continue? There have been encouraging signs lately for the opposition, which has made military gains against the regime of President Bashar al-Assad. But some observers say al-Assad’s grip on power remains strong.

CNN’s Nic Robertson and Nick Paton Walsh, who have reported from inside Syria, analyze the conflict and what the future may hold.

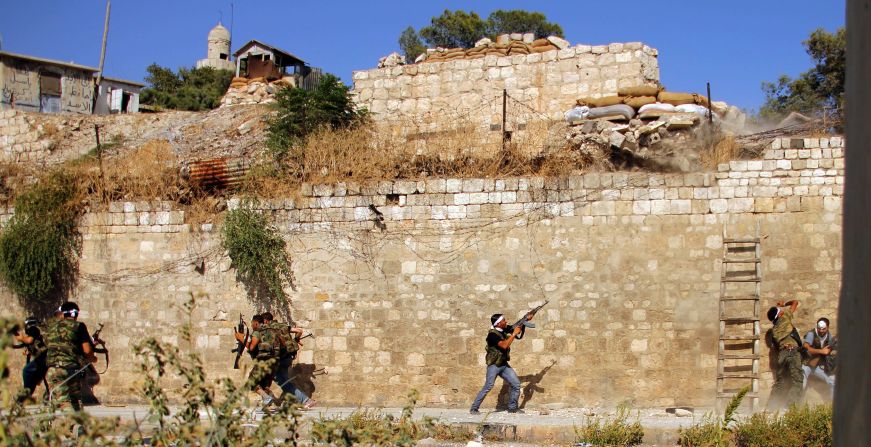

Will the rebels defeat the regime?

Nick Paton Walsh: I think there’s very little doubt that will happen. It’s not going to be one day in which there’s a decisive changing of the flags over a building in Damascus and then the whole country turns 180 degrees in terms of its government. But there have been weeks now of consistent bad news for the regime. …

That affects not only how people feel inside the regime’s inner circle, it affects how their sponsors feel. And, of course, it boosts morale for the rebels as well. So that real sense of momentum has been in place for months. It’s beginning to nip around the capital, and I don’t think any observer at this point thinks that the Assad government really has a chance in terms of retaining long-term power over the country.

Will al-Assad stay and fight until the end as he has said? Or will he go?

Nic Robertson: The rebels have said that they won’t rest until Assad is completely gone; they won’t negotiate with them. But he’s showing no signs of leaving whatsoever.

Perhaps there are early indications that Assad does realize that he cannot hold on to complete power as he has in the past. So perhaps what we’re seeing is the regime entering a new phase now where, rather than fight to hold on to everything, they’re fighting to have a better negotiating position in the future.

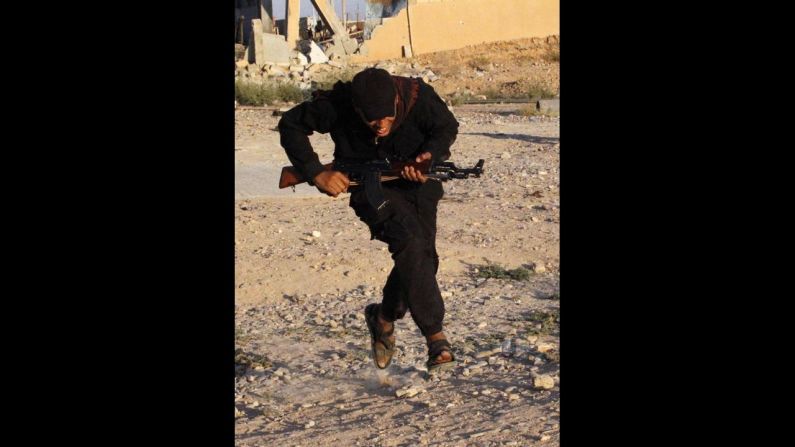

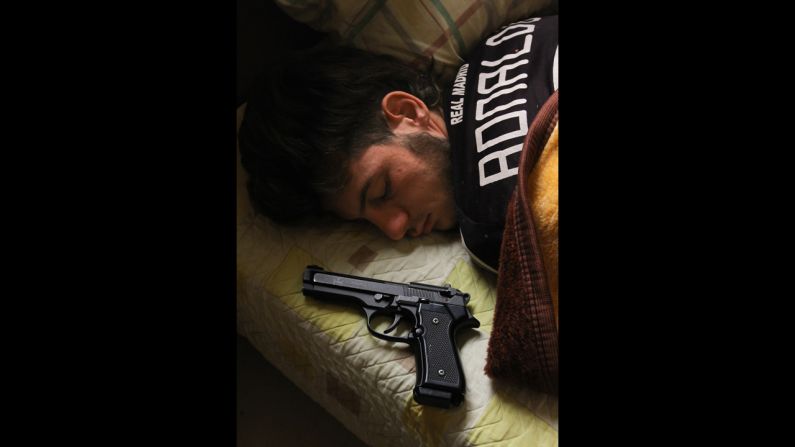

Paton Walsh: The question really is how messy is that final stand of Assad actually going to be? You’ll see pockets of these regime forces, particularly in the north, being left to their own devices. … The real problem of course is going to be how does the rebel militia, how do these disparate groups deal with these Allawi military prisoners once they’ve actually taken them into custody?

If al-Assad is overthrown, then what?

Paton Walsh: There will be a period of definitely chaos, warlordism perhaps, and sort of a vacuum whilst the armed groups who won the rebellion struggle for some degree of control over territory.

I don’t really agree with the more dramatic visions of a nightmare future in Syria that’s something between “Mad Max” and the Taliban. I think it’s going to be a much more watered-down version of that. I think there’s an optimism, perhaps amongst many Syrians, that they are educated, moderate in terms of the Islamic values they have. And remember also, this wasn’t really a rebellion started over Islamic principles. It is not Iran or Afghanistan. This was about trying to reject what they saw as a corrupt and repressive regime. …

It’s classic in these situations, once the major battle is finished, for world attention to radically drift elsewhere onto the next crisis. But that will be the moment when Syria needs help at its most. It will be the moment where the Syrians finally expect the West to actually step in now that the complicated issue of who’s arming who and who’s fighting who has been put aside.

What kind of help will Syria need?

Robertson: The economy in Syria is completely destroyed, and it’s going to take years to rebuild. So any notion that there can be a quick turnaround in 2013 is fiction.

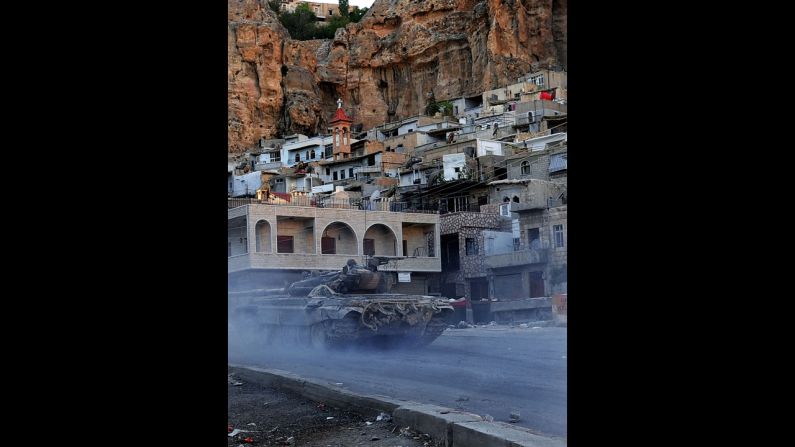

What we’re going to see in 2013 are large numbers of displaced people, millions internally inside the country. Thousands, tens, possibly hundreds of thousands of people without shelter, their homes have been destroyed. Large areas of Damascus, Homs, Hama, Aleppo have been destroyed, people without homes. And they’re going to be desperate for food.

Paton Walsh: I think once the majority of the violence ends, once the nuts and bolts of the civil war are behind them, then food, utilities will come back reasonably quickly because of the nature of where Syria is and who it’s bordered by.

The real question though is, how do you rebuild a country where so many districts of so many of its cities have already been flattened in many ways? I mean, two or three months ago, Aleppo was in pieces, really struggling to keep anything going.

Robertson: You have this whole opposition that hasn’t even engaged yet with the opposition outside of the country and the opposition that’s fighting there. So to see how they’re going to get together and govern together is very difficult. … Any sort of sense of these opposition groups want to coalesce around democracy, those are not the indications we have at the moment. They’re talking about “We won’t stop until we get rid of Assad.” These are not people who are showing a great ability to compromise so far.

How will the world respond or help or engage with the new Syria?

Paton Walsh: I think, in many ways, the process of that is under way, with the U.S. trying to influence a government in exile (and) many opposition figures gathering in Doha or Turkey to try and work out how that government would look like.

But the problem is that might not relate to the daily struggles people are facing on the ground inside Syria after what would be a two-year long war. And bridging that gulf between the men in suits in five-star hotels … and people on the ground who may be starving or missing the roof of their house from shelling is going to be the enormous challenge.

Robertson: Distrust is endemic region-wide. The distrust of the United States and Europe is deep-rooted in the culture in Syria already from 40 years of Assad rule, from watching what’s happened in other Arab countries, from hearing what radical Islamists say what the West is trying to do with Islam.

All these things have been fomenting in the background. And now you have a scenario where the West hasn’t come to the aid of the Syrians, so people are deeply angry.

I don’t think we’re going to find friends quickly in Syria. We’re certainly not going to win trust there quickly. And that’s going to make whatever we want to see – the international community wants to see happen in Syria – that’s going to make it much, much harder to achieve.