Story highlights

Stepped up fighting in Damascus signifies the beginning of end, one Syrian says

Rebel gains in past month: Taking oil fields, downing aircraft, getting weapons

Observers: Climate has changed in Syria, the war may be wrapping up

Hell came to Damascus months ago. It’s loud and scary in Syria’s capital. But now, this week, something seems different.

It feels worse. And that makes Leena feel better.

The Damascus resident, who sides with the rebellion, says it means the forces fighting to oust President Bashar al-Assad are winning.

“The rebels are winning, can you see?” she insisted during a Skype call Wednesday. “The regime feels threatened. They are scared. You can feel it here. It’s so tense.”

Leena, a former teacher in her 30s, told CNN that she’s hearing more helicopters hovering over her home this week. Traffic near the presidential palace is more hectic. Checkpoints are more intense. Blink, she said, and the price of gas goes higher.

U.S. spearheads diplomatic push on Syria

But the chaos, the uncertainty and booms of shells landing that keep her awake at night, now fill her with hope.

Damascus is the seat of al-Assad’s power. Rebel forces seem to be fighting harder than ever in the capital and, according to analysts and on-the-ground observers like Leena, al-Assad is acting like a boxer who fears his own knock-out is coming.

“The worse it gets now, the more we know the rebels will win,” she said. “We welcome this fight. It means we will wake up from this nightmare.”

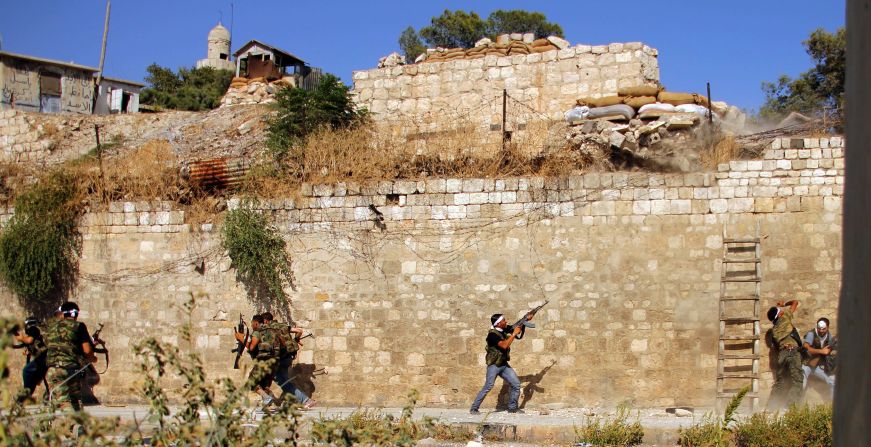

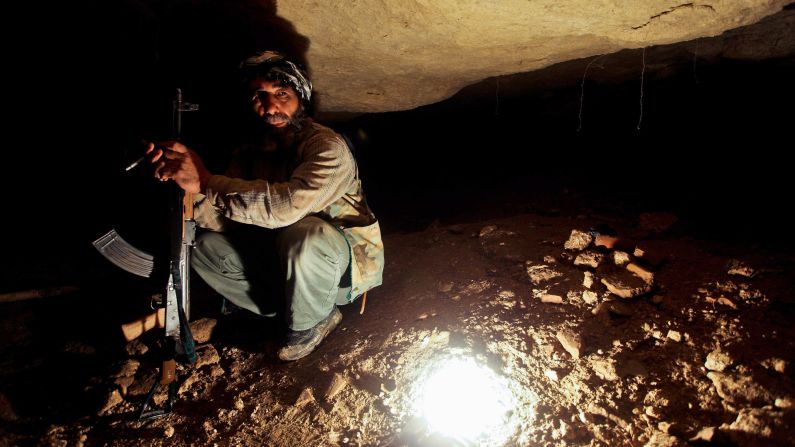

In the past several weeks, the rebels – once disorganized, dysfunctional and poorly armed – have made major strategic and psychological gains.

They have seized control of key oil fields and territory in important areas of the north. They have audaciously fired on the Damascus airport and downed several military aircraft.

Syrian rebels challenge al-Assad’s command of the skies

Rebels pounced on a key Air Force headquarters outside the northern city of Aleppo, seizing a large cache of weapons, and leaving the regime so desperate it bombed its own bases to prevent the rebels from getting any more.

It was another blow to Syria’s army, which experts say is spent, stretched thin by desertions and defections.

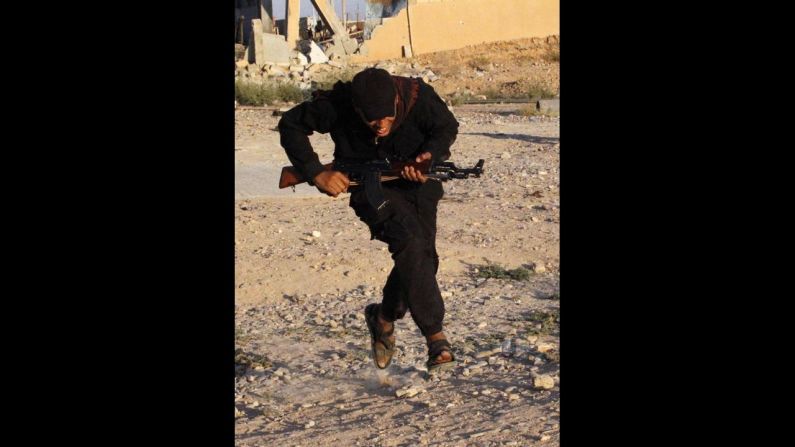

Syrian rebels in Damascus say they are more organized, better armed with heavy weaponry, and ready to “cleanse Syria” of government forces, Free Syrian Army spokesman Abu Qutada told CNN.

He said the rebels have “started the ending battle” of the war.

“We are conducting significant military operation inside the capital Damascus, this is a new stage,” Abu Qutada said Wednesday via Skype from the Damascus suburbs. “This is the decisive stage of our fight.”

And, international support for the rebels’ cause appears to be increasing. NATO recently approved sending Patriot missiles to Turkey, which supports the rebels. France and other pivotal European countries have said they also back the movement against al-Assad.

Those opposed to al-Assad – including the United States – have said for months that the Syrian leader’s days are numbered. Now, there are signs of desperation:

Al-Assad is reportedly considering his asylum options, despite insisting that he will “live and die in Syria.” He is also reportedly considering using chemical weapons on his own people.

And the Syrian government has been blamed for temporarily shutting down Internet service in the country last week, an alleged attempt to thwart rebel communication.

So, with key rebel advances in the north and signs of desperation in Damascus, many observers believe the end is in sight for Syria’s 21-month-old brutal civil war.

The regime is clinging to the capital, Damascus, as rebels chip away at the military, according to regional analysts. And the rebels don’t have the clout to go toe-to-toe with the government in the center of Damascus, according to senior analyst Joseph Holliday.

“It (the Syrian rebellion) will not be able to overthrow the Assad regime for the foreseeable future,” wrote Holliday of the Washington-based Institute for the Study of War.

But, he said, that doesn’t mean a certain victory for al-Assad’ forces.

“The regime does not have the forces required to hold all of Syria, and its control is steadily eroding across the country.”

Attack not best way to stop Syria’s chemical weapons

‘We thought it would be over fast’

If this is a crossroads inthewar, the road leading to it has been long and hard.

Syria’s conflict began in March 2011, when protesters like Leena took to the streets to peacefully call for more freedom. They were inspired by Arab Spring demonstrations that toppled dictators in Egypt and Tunisia.

“I have to tell you, we thought it would be over fast,” Leena said. “I never thought it would come this far. None of us expected to lose this many friends.”

She pauses, her voice breaking.

“We … knew the regime was strong, but not that … fierce. I guess we did not expect how terrible it would be.”

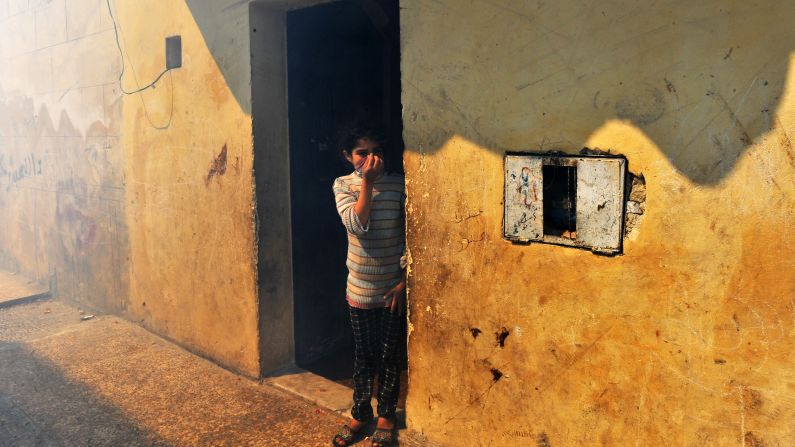

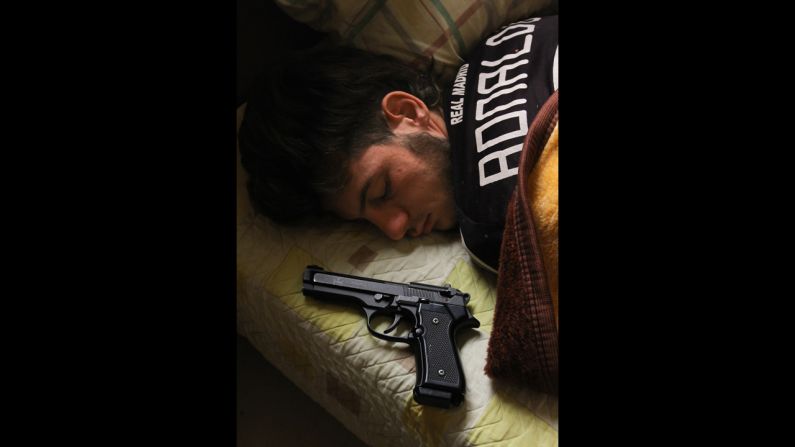

The most heinous acts man is capable of inflicting on others have happened in Syria.

Journalists, Syrians and human rights workers say the military has gone house to house and shot dead entire families.

Shelling kills 10 children on a playground

Children, they say, have been abducted, tortured and killed and dumped on their parents’ front door. There are allegations of underground torture facilities across the country.

The Syrian government denies it is targeting its own people, saying it has gone after “terrorists” that are seeking to overthrow the government.

While it’s tough to pin down estimates of regime forces and rebel fighters, most analysts agree that the Syrian government still retains vast superiority in firepower over the rebel fighters.

Yet there’s a “turning process” going on in Syria, according to analyst Jeffrey White, who recently visited the region.

“Morale, combat spirit (within regime forces) seems to be degrading,” said White, a defense fellow at The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. “The rebels are getting stronger, they keep forming units, they keep getting defectors, they keep getting personnel.”

The rebel movement has grown bottom-up, a fighting force replete with Syrian army defectors, Syrian citizens, and Islamists – from inside and outside the country. Regional commands are emerging, and units are working together.

The government has ceded huge swaths of territory in the north, and hasn’t been able to oust rebels from the most populous city of Aleppo, which is almost fully under rebel control.

As fighting subsides, Aleppo residents find little left

“The opposition pretty much owns Syria,” said Michael Weiss, research director at the UK-based Henry Jackson Society. “The regime hardcore – they are in the red in the ledger now, not in the black.”

The rebels have now emerged as a “quasi-professional army.” He said their advances have made make it “much easier to impose a no-fly zone in the north of Syria”– if that happens.

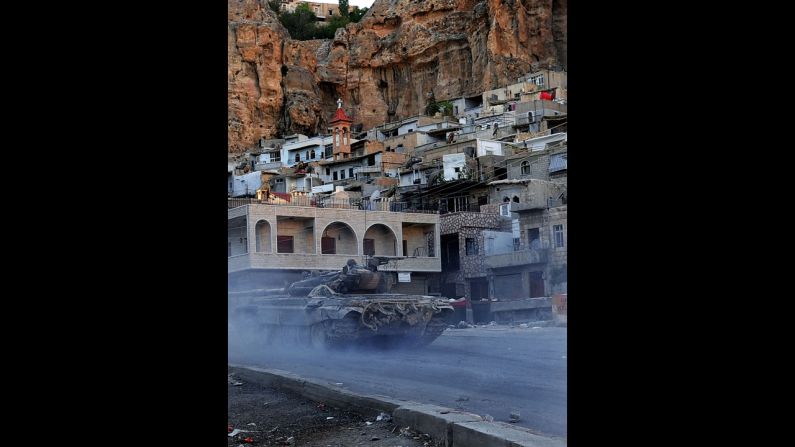

Yet, the Syrian military hopes to gain advantage with its superior firepower by locking down key urban centers, such as Damascus and Homs.

But Weiss notes that the government hasn’t had a major military victory in the north of Syria for months, and the rebels have effectively encircled Damascus.

It also hasn’t embarked on major ground offensives, like the one in Aleppo earlier this year. Such activity puts the army at risk of more defections and desertions.

Syria’s Assad regime has fight left despite rebels’ advances

Frustration, optimism

As analysts study every move by the rebels and government forces to determine Syria’s endgame, the people living there – some filled with hope, others mired in frustration – want to know when it will end.

Echoing a common sentiment among many Syrians, a Syrian blogger in Homs, who calls himself “Big Al,” says recent attempts by the international community are all too little, too late.

“Syrians are doing things on their own and no one will help them,” he told CNN.

“The world watched and is still watching Syrians get slaughtered and did nothing and will continue to do nothing, so empty threats mean nothing to us,” he said.

He dismissed recent reports that NATO had approved deploying Patriot missiles near the Turkey-Syrian border as an “empty threat.” He also rejected the recent outcry over the threat of chemical weapons against Syrians, saying, “the only reason they’re saying these threats is to pretend that they might actually do something and they won’t.”

“They only don’t want chemical weapons to be used against Israel but I know, and everyone here knows, that if they were used against Syrians, nothing will happen and no threats will come true.”

In Damascus, Leena remains optimistic about an impending rebel victory – but she admits that the nearly two-year-long road to revolution has changed her and others risking their lives for a new Syria.

Back then, they were idealists, beginner revolutionaries.

“You want your freedom, democracy, better healthcare, work, education,” she said. “We wanted dignity.”

She loved her life before, but she is going to love it even more when the rebels win.

Because they will win, she insists. Soon.

“Haven’t we shown that?” she asked. “Doesn’t the world understand that by now?”

Syria’s chemical weapon potential: What is it, and what are the health risks?

CNN’s Yousuf Basil contributed to this report