Story highlights

Voters in Colorado and Washington approved legalizing marijuana for recreational use

The federal government, which still considers marijuana possesion a crime, hasn't weighed in

There are many similarities in the move to legalize pot and the end to alcohol Prohibition

Detractors of both drugs have also used similar tactics, including stoking racial fears

Turn on a television show or open a magazine in the United States today and you’re bound to see someone with a drink in hand – something unthinkable nearly a century ago.

Advocates of marijuana hope that someday that drug will emerge from its current “prohibition” period, the same way alcohol did, and become not only legal but as socially acceptable as having a drink.

Could that happen? Depends who you ask. Advocates point to the November ballot in Colorado and Washington, where voters approved legal pot for everyone, not just for those who have a medical reason.

Detractors of marijuana legalization say there are serious health consequences, and argue the drug is often a gateway to more harmful, addictive substances.

However pot’s future is going to play out in this country, its recent path to limited legalization has interesting parallels to alcohol, which was banned by the federal government in the 1920s and early 1930s. The Prohibition era gave rise to an underground market for booze, produced by unregulated bootleggers and moonshiners, and consumed in back-alley speakeasies.

A few years after Prohibition’s repeal, the federal government banned marijuana, hardly as popular and socially acceptable as alcohol. It would be decades before supporters of pot would mobilize and successfully get the drug legalized in some states.

Advocates and detractors for both drugs seem to have read from the same playbook,stoking fears based on prejudices and questionable scientific studies.

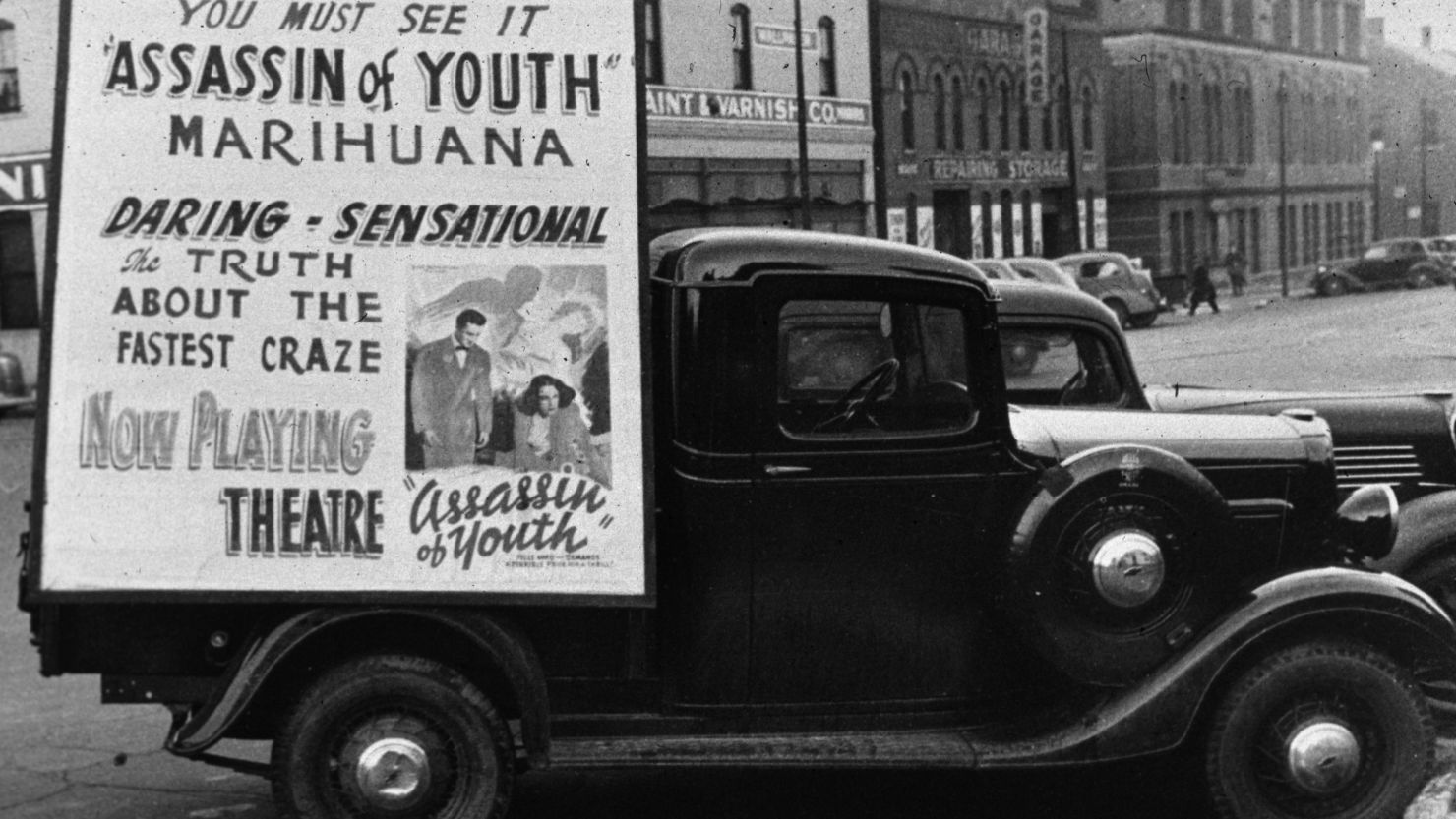

Rather than discuss issues of substance, opponents of marijuana in the early 20th century preferred to exaggerate its effects and pin its use on foreigners and black entertainers.

It was a familiar tactic that had panned out well in pre-Prohibition days.

In a 1914 speech before the House, Rep. Richmond Hobson of Alabama warned that booze would make the “red man” savage and “promptly put a tribe on the war path.” He added, “Liquor will actually make a brute of a Negro, causing him to commit unnatural crimes.”

Twenty-three years later, while arguing for marijuana prohibition, Harry Anslinger also played on Americans’ fear of crime and foreigners. The Bureau of Narcotics chief spun tales of people driven to insanity or murder after ingesting the drug and spoke of the 2 to 3 tons of grass being produced in Mexico.

“This, the Mexicans make into cigarettes, which they sell at two for 25 cents, mostly to white high school students,” Anslinger told Congress.

The term marijuana itself was intended to stoke alarm, as many Americans in the 1930s were already familiar with other terms for the drug, according to Michael Aldrich.

“(The drug’s opponents) preferred the word marijuana instead of cannabis or hemp because people thought it was some new devil drug from Mexico,” said Aldrich, the former curator of what is now Harvard University’s Fitz Hugh Ludlow Memorial Library, a collection of psychoactive drug-related literature.

“All of a sudden, there’s this new thing being introduced by outside people,” Aldrich, who is credited with writing the first dissertation on marijuana myths and folklore. “It was all a bunch of crap.”

‘Reefer Madness’ vs. ‘Medicinal marijuana’

In the shaky, handwritten opening lines of the 1936 movie “Reefer Madness,” marijuana is described as a “violent narcotic” that first renders “sudden, violent, uncontrollable laughter” on its users before “dangerous hallucinations” and then “acts of shocking violence … ending often in incurable insanity.”

Watching the movie today (available on YouTube) might provoke “uncontrollable laughter” – even from those who oppose marijuana legalization. Yet the movie’s message was based in part on scientific studies that were considered legitimate at the time.

There were similar claims about alcohol in the years leading up to Prohibition. While the Anti-Saloon League painted drinking as un-American and immoral to convince counties and states they’d be better off saloonless, they also leaned on hokey research, according to Garrett Peck, author of “The Prohibition Hangover.”

The ASL used “quack medical experiments” to demonize beer, wine and liquor, Peck said. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union went into classrooms purporting to demonstrate the effects of alcohol by pouring it directly onto sheep and cow brains, quickly transforming the pink organ to a grayish hue, he said.

“It was scientifically without merit because when you drink, it goes through your stomach,” Peck said. “Otherwise, most of us would be lobotomized.”

That’s not to say there aren’t substantial health detriments to alcohol and marijuana use.

Both can have impacts on brain development in younger users. Smoking marijuana can cause respiratory issues. Long-term alcohol consumption is linked with a host of cardiovascular and nervous system problems, not to mention cirrhosis. And that’s the short list.

But just like opponents have overplayed the drugs’ detrimental effects, advocates have exaggerated their benefits.

Think “medicinal.” In 2010, ahead of California’s failed marijuana-legalization referendum, several medicinal marijuana users shared their symptoms and ailments.

Among them were AIDS patients who needed it to boost their appetites. The husband of a cervical cancer sufferer recalled how cream-based marijuana soups eased his wife’s agony more effectively than the powerful painkiller Dilaudid.

Others, however, told CNN of lesser maladies. One said with a smirk that he’d jammed his thumb. Another said he’d been stressed out at work and explained how less-reputable dispensaries had doctors in back rooms who prescribed pot for almost anything.

It was no different when alcohol was banned, Peck said. Despite the American Medical Association saying alcohol had no medicinal value, the Volstead Act, which led to the federal ban on alcohol, stated that no one could prescribe alcohol except “a physician duly licensed to practice medicine” – much to the delight of the nation’s Jay Gatsbys.

“Yes, medicinal whiskey – all of a sudden, all of these doctors are saying we need to prescribe this because there’s so much money to be made. You could prescribe a pint a week,” Peck said. “We know enough about alcohol now; it’s not medicinal.”

As Prohibition expert Daniel Okrent wrote in 2010, “… all too often, ‘medicinal’ has been a cynical euphemism for ‘available.’ “

John Kane, a U.S. district judge in Colorado, explained that while there was a medical exception to alcohol Prohibition, health had little to do with its repeal.

No one was clamoring to make brandy legal to cure the country’s headaches, explained Kane, whose father was a pharmacist during Prohibition and prescribed brandy to his patients.

Rather, the nation had grown weary of the organized crime that accompanied Prohibition, he said.

Many of the immigrant groups vilified by the teetotalers formed the organized crime units that plagued Prohibition days, he said. Prior to the ban on alcohol, gangs generally ran numbers, extorted folks or charged fees for protecting neighborhoods.

“Then Prohibition came along, and that basically gave them an American Express black card,” Kane said. “It subsidized criminal activity in this country.”

The price of legalization

Just as Prohibition bore Al Capones and strengthened the Frank Costellos and “Lucky” Lucianos, American drug prohibition has spawned a host of cartels south of its border. They wage war against each other for the rights to the most lucrative illegal drug market on Earth – the United States – which by some estimates, consumes two-thirds of all the illegal drugs in the world.

Yet there is a major difference between Capone’s henchmen and the Mexican cartels: “The violence is not to the scale of what’s going on in Mexico,” Peck said.

The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre of 1929, one of the most heinous crimes of the era, left seven dead. That many could be murdered in a Mexican border town on your average Wednesday.

How big a hit the cartels would take if the United States legalized pot is a matter of debate, and conclusions vary widely. While U.S. officials said in 2009 that 60% of cartel revenue came from weed, the RAND Corporation said the following year that “15-26 percent is a more credible range.”

A report this month by the Mexican Competitive Institute predicted Mexican drug organizations, namely the Sinaloa Cartel, could lose almost $2.8 billion just with the legalization votes in Colorado and Washington.

When Prohibition was repealed in 1933, states saw two immediate benefits aside from neutering the criminal gangs, the first being that they could regulate the product.

Under Prohibition, unscrupulous bootleggers had manufactured moonshines and bathtub gins that could render tipplers blind or dead. Once alcohol was legal, you had a return to quality control, Peck said.

The second immediate benefit? They could tax the hooch.

“It was a huge consideration. The Great Depression was going on at that point,” Peck said. “FDR pays for the New Deal with excise taxes on alcohol and tobacco.”

In President Franklin Roosevelt’s first two terms, federal taxes jumped from $1.6 billion in 1933 to $5.3 billion in 1940.

How that might translate to marijuana taxation today is debatable, and the ends of the gamut are nowhere near middle ground.

“Medical marijuana helped save the economy in California … The counties north of San Francisco survived the recession through marijuana,” said Aldrich, the marijuana historian.

He was referring to the Emerald Triangle, which is known for producing and exporting some of the country’s highest-grade cannabis.

On the other side, you have President Barack Obama’s drug czar, Gil Kerlikowske, who emphatically denied that marijuana legalization would prove a boon to state coffers. Taxes on alcohol, he told CNN in 2010, amount to $14.5 billion a year, where as the social costs are closer to $185 billion.

Ahead of the recent ballot initiatives in Colorado and Washington, the Colorado Center on Law & Policy estimated that legalization would yield $60 million in state and local revenue and savings by 2017, and perhaps double thereafter. And Washington’s Office of Financial Management estimated that a “fully functioning” marijuana industry could bring in nearly $2 billion in revenue over the next five years.

“Fully functioning.” Therein lies the rub.

Both the Colorado and Washington estimates came with caveats explaining the obvious: Any revenue projection is contingent on the federal government not enforcing the laws that still render possession of an ounce of marijuana illegal – even in Colorado and Washington.

University of Virginia law professor Richard Bonnie, co-author of “Marijuana Conviction: A History of Marijuana Prohibition in the United States,”said it’s a tricky equation.

“There is something attractive about saying you’ve got this underground market that’s not going away, that you’re missing a tax opportunity,” he said. “The amount of tax revenue you’re going to derive from it is going to depend on what your regulatory approach is going to be.”

Bonnie was part of the commission that futilely recommended marijuana decriminalization to President Richard Nixon in the 1970s, but he is quick to emphasize that states must step gingerly if marijuana is legalized.

There were many problems with regulating alcohol post-Prohibition, and there still are today. More than a third of eighth-graders say they’ve used alcohol, and almost three-quarters of high schoolers have gotten drunk.

“You have to have a model that doesn’t seem to actively encourage use in ways that are harmful to society and the individual,” he said, noting the modern regulation of cigarettes provides an admirable model.

Though the Tax Policy Center reports state and local governments collected $17.3 billion in tobacco taxes in 2010, cigarette use, especially among youngsters, has dropped almost 33% since 2000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Looking into the crystal ball

When alcohol Prohibition was lifted in 1933, regulation was left to the states. Oklahoma stayed dry until 1959, Mississippi until 1966.

Bonnie said he sees marijuana legalization advocates leaning toward a similar model. But, he warns, “there is a social cost to a regulatory regime that taxes and becomes dependent on the revenue.”

Overtax it, and you create another dilemma: black markets and the smuggling of marijuana from state to state, a la post-Prohibition. Canada and Sweden learned that lesson with cigarette taxes in the 1990s.

All of this is putting the roach before the joint, of course. Marijuana, no matter what Colorado and Washington say, remains illegal at the federal level.

Experts are reluctant to forecast when that might change. Aldrich predicts federal legalization by 2017, but he concedes that in 1969 he predicted the federal government would relent by 1979.

Judge Kane said he foresees marijuana following a similar path as alcohol. Toward the end of Prohibition, judges wantonly dismissed violations or levied fines so trivial that prosecutors quit filing cases, he said.

While he sees marijuana laws that target kingpins, traffickers and those who engage in violence remaining in place, he believes possession laws are endangered, he said.

“The law is simply going to die before it’s repealed. It will just go into disuse,” Kane said. “It’s a cultural force, and you simply cannot legislate against a cultural force.”