Editor’s Note: Ruben Navarrette is a CNN contributor and a nationally syndicated columnist with the Washington Post Writers Group. Follow him on Twitter: @rubennavarrette.

Story highlights

Mexico's incoming president Enrique Pena Nieto meets with Obama on Tuesday

Ruben Navarrette: His election means a return for PRI, party that held presidency for 71 years

Mexican people are tired of crusades such as drug war, want a return to basics, he says

Navarrette: Obama, Pena Nieto have opportunity to help each other and their nations

On a recent trip to Mexico City as part of a delegation of Mexican-American and American Jewish leaders, I heard a joke that is circulating among the intelligentsia:

“Mexicans are observing daylight savings time in a major way. On December 1, they’ll turn the clocks back 100 years.”

Actually, it’s not quite a century. The reference seems to be to 1929, when the Institutional Revolutionary Party (or an earlier version of it) kicked off what would be a 71-year hold on the presidency. In the 20th century, PRI became notorious for the brutality, corruption, election rigging, and brazen thievery of its leaders and their cronies.

Now, after 12 years out of power, the PRI is returning to the scene of its crimes. The party is about to retake the reins of power thanks, in large measure, to the popular appeal of a handsome, charismatic and personable 46-year-old lawyer who seems to have stepped right out of central casting. He is even married to a beautiful telenovela actress.

Enrique Pena Nieto is set to take office on December 1.

Mexicans feeling persecuted flee U.S.

Get our free weekly newsletter

This has been a Hollywood ending for a political party that was, just a few years ago, on the brink of extinction.

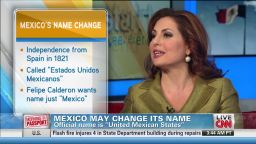

The first blow came in 2000 when the National Action Party’s Vicente Fox broke the PRI’s hold on the presidency. Then came heavy losses for the PRI in Congress during the 2003 midterm elections. That was followed by another victory for the PAN in 2006, when Felipe Calderon took the presidency – and the PRI candidate came in last among the top three political parties. But then, the PRI regained some ground in the 2009 midterm elections – in part, it seems, because the Mexican public was so battle-weary after three years of Calderon’s bloody war against the drug cartels.

Don’t get me wrong. The drug war is messy but necessary, and that’s true in both the United States and Mexico. Legalizing drugs and making them more readily available would, in either country, increase the number of addicts, lead to more street crime to feed consumption habits, destroy scores of families, make people less productive and more dependent, and empower criminals by surrendering the fight.

Opinion: Mexico, U.S. ties ripe for major expansion

And yet, it all comes at a high cost. South of the border, the drug war has resulted in the deaths of more than 50,000 Mexicans. And, because it has become more difficult to move drugs to the United States and Canada, it has brought to Mexican society a domestic drug consumption problem that Mexicans have long been content to export to the United States.

Even the man who started the war – or, as Mexicans like to say, stirred the hornet’s nest – now claims that it’s not winnable. Calderon, the outgoing president of Mexico, recently conceded in an interview with The Economist that ending the consumption of drugs and drug trafficking is “impossible.” As Calderon sees it, the real goal of the drug war is to disrupt the drug trade and keep money out of the hands of killers who terrorize the Mexican people.

Those people are now taking another look at the PRI. The way they see it, the party may have been corrupt, but at least it was competent. Unlike the PAN, whose leaders seem obsessed with causes and crusades – for Fox, defending Mexican immigrants in the United States, and for Calderon, the drug war – the PRI kept the trains running on time.

Can Enrique Peña Nieto save Mexico?

As many Mexicans see it, the country needs to move on to other business. They expect Pena Nieto to lead the way. They may not want a complete and unconditional surrender to the drug cartels, but they could live with an accommodation that included an end to the violence.

The battle against the drug cartels is sure to be on the agenda Tuesday when Pena Nieto is scheduled to visit the White House and meet with President Barack Obama.

I had the chance to meet Pena Nieto during my trip and hear about his vision for building a new and improved Mexico. Despite the knocks that he has taken from the Mexican press and the elites for not appearing to be book-smart, he has more than his share of “EQ” – emotional intelligence. This will carry him far with a Mexican public that, at this point, wants to have leaders that it can relate to, who will address its everyday concerns.

Like a certain recent U.S. president from Texas, Pena Nieto is taken lightly by many as he enters the office. Yet sometimes being underestimated can be helpful. And just as George W. Bush reached the height of his popularity after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Pena Nieto might yet surprise his critics and rise to the challenge of dealing with a major crisis when faced with one.

In his meeting with Obama, the Mexican president-elect is likely to dwell on what he believes the U.S. can accomplish for Mexico. This will probably include delivering the last few hundred million dollars worth of equipment and supplies that is owed to Mexico to help it fight the drug cartels under the $1.4 billion Merida Initiative; safeguarding the rights of Mexican immigrants in the United States regardless of legal status; and supporting the creation of a North American trade alliance (the US, Mexico and Canada) that could compete with Asia and the European Union on the stage of global commerce.

But Pena Nieto should also focus on what Mexico can accomplish for the United States. He could pledge to continue the drug war and keep the pressure on the cartels, in the spirit of the Merida Initiative; vow to create more jobs and better-paying jobs in Mexico, especially in the poorest regions that produce most of the illegal immigrants to the United States; commit himself to addressing the severe inequalities between Mexicans, closing the huge gap between rich and poor, and expanding the middle class in a country where more than 50% of the population still lives in poverty; and pledge to open up the Mexican petroleum industry to investment from North America and partnerships with American and Canadian oil companies.

All of this would benefit not only the relationship between Mexico and the United States, but also the lives of Mexicans. Those people seem to be tired of crusades. Now, it appears that they want their leaders to focus on the basics: creating better-paying jobs, protecting the population, expanding trade, improving access to technology, developing infrastructure in rural areas, and improving relations with foreign countries and trade partners.

Those are some of the challenges facing Enrique Pena Nieto. How he addresses them will tell us whether the Mexican people who elected him, and returned his party to power, made a wise choice or a bad mistake.

Follow @CNNOpinion on Twitter

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Ruben Navarrette.