Story highlights

A diverse coalition joined forces to bring historic change on same-sex marriage

Minnesota parents of a fallen soldier who was gay worried his death would be in vain

Republican in Maine feared backlash but broke with party line anyway

A preacher in Maryland spoke up to counter media dominance of right-wing pastors

After their son was killed in battle in Afghanistan, Lori and Jeff Wilfahrt crisscrossed their home state of Minnesota. They spoke at churches, schools, book clubs. They spoke of Cpl. Andrew Wilfahrt’s love of country and the Constitution.

They spoke, too, of grief. They are a mother and father who utterly miss their son, a soldier who was openly gay.

On Tuesday, November 6, the Wilfahrts entered their polling station in Rosemount to vote against a state constitutional amendment defining marriage as solely between a man and woman. Both parents wondered: Had their boy died protecting homophobes who would deny him rights back home?

In Frederick, Maryland, the Rev. Barbara Kershner Daniel had lived with guilt for nearly 25 years. A fellow preacher who was gay had asked her to officiate his wedding with his partner. She told him no.

“Why did I do that?” she has asked herself ever since.

Mark Ellis, the former GOP state chairman in Maine, knew where he stood on the issue of same-sex marriage. Yet he struggled with whether it would hurt him professionally to break from his party.

In the northern suburbs of Seattle, middle school band and orchestra teacher Michael Clark had always spoken of dignity and respect for all. He and his partner of 18 years sat together at their dining table to vote early this year.

Their ballots weren’t just votes. They were an affirmation of their love.

iReporters share stories, images from same-sex weddings

From Minnesota to Maryland, from Maine to Washington, this mixed coalition of voters – grieving parents, a preacher, a lifelong Republican and a gay couple – joined forces to push for historic change on same-sex marriage.

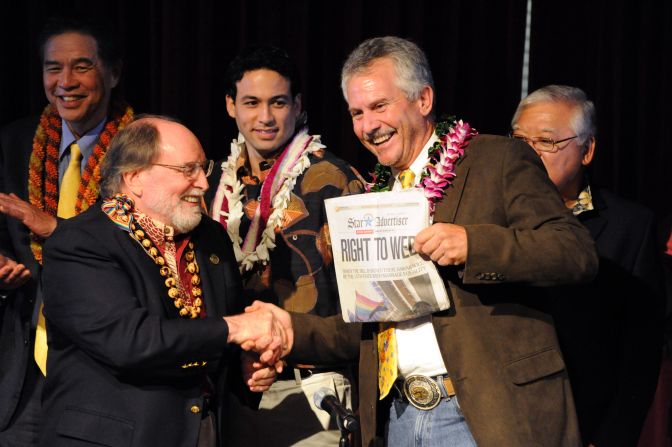

Never before had a state rejected a constitutional amendment to prevent gays from marrying. Minnesota did just that, in part spurred by the Wilfahrts’ activism.

Never before had voters approved laws allowing same-sex marriage. Maryland, Maine and Washington did just that. Those states may not have garnered enough votes if ordinary citizens like Daniel, Ellis and Clark had remained quiet.

Each took up the cause for personal reasons shaped by life experiences. Together, they surprised America; their voices emerged as a sign of a more progressive electorate that’s grown tired of arguments that say marriage between two men or two women undermines the institution and the very fabric of society.

This shift in beliefs was captured in a recent Pew Center poll that found 48% of Americans now favor same-sex marriage. Just four years ago, only 39% felt that way.

Before the election, gay marriage had been approved in six states – Connecticut, Iowa, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York and Vermont – through the courts or legislatures. What made November 6 a watershed moment was that the people decided.

The issue, though, is far from settled. Despite the recent victories, 32 states have altered their constitutions to ban same-sex marriage, and it seems inevitable that the Supreme Court will weigh in this term.

The Supreme Court justices this month will begin considering several cases involving same-sex marriage, including one testing the constitutionality of California’s Proposition 8, which says “only marriage between a man and a woman is valid or recognized in California.” Other cases challenge the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act, which, among other things, deprives same-sex couples of federal benefits.

The Wilfahrts would have preferred not to have been thrust into the debate. They’d give anything to celebrate Thanksgiving with Andrew at their oak table once more. But their fate changed on February 27, 2011, the day Cpl. Wilfahrt, 31, was blown up while on foot patrol.

On Election Day, the Wilfahrts received something so powerful, so poignant, so unexpected – a feeling they had not experienced since that awful knock at their door.

Purging guilt

Rev. Barbara Kershner Daniel was a brand new preacher living in Pennsylvania 24 years ago. She had given birth to her first son. While she was on maternity leave, a pastor filled in for her at the pulpit. “A very nice man and incredible preacher,” she remembers.

He was gay, and he asked her to officiate a ceremony for him.

“I declined,” she says. “I was in my first parish. I wasn’t sure what the reaction would be, and I’ve regretted that ever since.”

Like so many, she struggled with the concept of civil unions versus marriage, too. It’s not that she didn’t like gay people. She was welcoming to friends and congregation members who were gay. “I was always really aware of this group of folks in the church who were disenfranchised.”

As she thought about the issue more and met more gay people over the years, Daniel’s view evolved. “When you say civil union, it doesn’t have the same meaning.”

Same-sex couples find their stride

Daniel is now pastor of the Evangelical Reformed United Church of Christ in Frederick, Maryland. The United Church of Christ passed a resolution in 2005 affirming marriage equality. Daniel’s church voted two years later to be an affirming congregation, allowing gays and lesbians to be active in all aspects of the church.

“We’re a church where people are welcome, where families are nurtured, where families are families.”

She believes right-wing preachers get too much air time, that for far too long, conservative pastors have drowned out the voices of progressive people of faith.

The Maryland legislature passed marriage equality, and the governor signed it into law earlier this year. But opponents gathered enough petition signatures to force a vote this year.

Daniel watched from the sidelines last year as conservative clergy led the charge to try to block the legislation and ban gays from marrying. “Not doing anything this year was not an option,” she said.

She and other leaders helped form an interfaith group called AMEN – Advocating for Marriage Equality Now. They received social media training on how to spread posts rapidly across Facebook. They knocked on doors, placed hundreds of phone calls and wrote letters to the editor to area newspapers, anything to reach out to the state’s more progressive electorate.

“The evolution on my journey is: Ever since that time I said ‘no,’ I’ve said, ‘Why did I do that? They love each other. Why is that any different than the other couples I’m marrying?’”

As she cast her ballot, she thought of all the families that could be made whole. “I must admit that it was a bit emotional,” she wrote on her Facebook page.

The Sunday after the vote, she stood before her congregation and declared, “We are generous, we are passionate about justice and we support love for all families. Let’s give it up for Maryland!”

The more than 200 members cheered wildly.

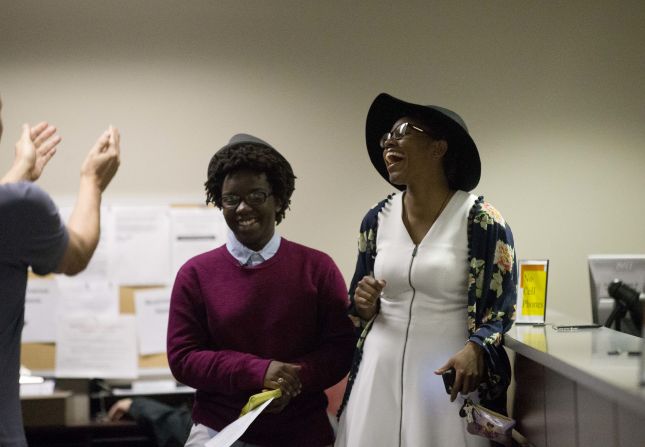

In the church bulletin, a gay couple who have been together for more than 25 years invited everyone in the church to their wedding on January 5.

Daniel will marry them.

Fighting bigotry

When Mark Ellis was about 3 months old, a white couple from Maine adopted him in the Philippines. His father was in the Air Force and stationed there. For years, they lived the rolling stone life of a military family, moving from base to base. Ellis played with kids from all walks of life, of all different races.

But when he was 10, his father retired, and the family moved back to Maine. Ellis was suddenly dropped into an all-white environment, the only kid of a different race.

“I had never experienced racial bigotry until we got back to my father’s home state,” he says.

He heard sneers. Kids mocked him in their pretend Asian voices. They called him “gook.”

Being bullied would shape him and his views. “My perspective was built up on being different on this journey through life.”

Now 51, Ellis was drawn to the Republican Party during the Reagan era. He found Then-President Ronald Reagan’s calls for personal responsibility and growing the economy through private enterprise inspiring. He’s been a Republican ever since, eventually becoming the chairman of the GOP in Maine. He is currently the communications director for Maine Senate Republicans.

As this election neared, Ellis thought long and hard about how vocal he should be about same-sex marriage.

“That’s something I had to work through personally with an eye on who I’m going to offend and am I going to limit myself professionally or politically. I was sort of weighing all of those things on how public I should be.”

He couldn’t help but recall his own marriage, 28 years ago. He knew the nation once barred interracial couples like him and his wife, who is white, from marrying. Opponents then used arguments that sound eerily similar to those against gays today, he thought.

Ultimately, Ellis joined a coalition of Republicans for marriage equality and took to his blog to broadcast his support.

“My vote of ‘yes’ is not based in some radical desire to toss tradition out on its ear or to discount marriage as we know it today,” he wrote. “My vote comes from the simple notion that acknowledges the powerful, positive potential [that] loving and committed couples hold for their families, communities, and society.”

A vote for dignity

Michael Clark, 35, blazed a trail early on. He was the first openly gay person in his high school in southern Oregon. He faced constant bullying, but he also had “people around me saying that I deserve respect and dignity.”

“I had teachers, I had friends, I had community members who would jump to my defense,” he says.

At Southern Oregon University, he and his partner were among the first to get a domestic partnership in the town of Ashland. He was 20. “We just knew early on that we wanted to spend the rest of our lives together.”

Yet they longed for more. They got married in Canada in the early 2000s, but it felt empty. “It was odd knowing that we were married and equal people in Canada,” he says, “but the moment we crossed our borders again, it was all bets off.”

They have been together half their lives now. Living in the suburbs of Seattle, the two were anxious to vote on same-sex marriage in Washington.

“My husband and I are not a Norman Rockwell painting, but we’re a family that loves one another,” he says. “I don’t want to be domestically partnered forever and ever. I want to be married to the person that I love.

“Here’s the exciting thing to me. We get to define what America is, and America continues to evolve.”

As a teacher who hopes to become a principal, Clark kept his political beliefs to himself inside the classroom. Casting his ballot, he thought of the leaders within the gay rights community who had gone before him; of his partner; and of the future generations who would grow up knowing “they can love and marry whomever they want.”

“It really felt like it was a vote for dignity and respect and standing up for that,” he says.

Fellow teachers visited his classroom the day after the election. They offered congratulatory hugs.

On December 6, he and his partner will call in sick. That day they will wed.

A parents’ love

Among the items in the Wilfahrt home in Minnesota is a pen from President Barack Obama. It was used to sign the repeal of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” the policy that required gays in the military to hide that part of their lives or risk being kicked out.

The White House sent the pen to the Wilfahrts after Andrew was killed in Afghanistan, the first gay soldier killed after the repeal.

Cpl. Wilfahrt became a rallying cry for gay rights supporters. Floats bearing his image have wound down the streets of Minneapolis and St. Paul at the annual pride parade the last two years.

Republican state Rep. John Kriesel, a war veteran who was nearly killed by a roadside bomb in Iraq, passed around Wilfahrt’s image at the legislature. He told his colleagues: “I cannot look at this picture and say, ‘Corporal, you were good enough to fight for your country and give your life, but you were not good enough to marry the person you love.”

Kriesel’s speech was turned into an advertisement by supporters of marriage equality and broadcast around Minnesota before Election Day.

Lori Wilfahrt worried her son’s death would be in vain if they failed to stop the amendment.

Jeff Wilfahrt told anyone who would listen that his son and other gays were citizens of the state who should never be denied rights. “Very early on,” he says, “we took a position to protect citizenship.”

Never afraid to voice his opinion, Jeff once challenged opponents as to how they would prove a couple who wanted to get married were a man and a woman: “Will you as a human being, as an American, as a Minnesotan, be asked to open your trousers or to have your skirt lifted when applying for a license to marry?”

On Election Day, the Wilfahrts arrived at their polling place and waited as the poll worker scrolled through the list of registered voters. They both saw it: Right above Jeff’s name was Andrew’s.

They told the poll worker their son was killed in Afghanistan, that his name shouldn’t be on the list. She was embarrassed and said, “I know. I’ve seen both of you on television.”

The two then went in to mark their ballots. Lori checked hers about 10 times before casting it. “To me, in some ways, it’s the last thing I can do for him.”

As they prepared to leave, an election judge pulled them aside. They were asked to sign an official deceased voter voucher.

“Here you are before your government declaring your son is dead after that vote,” Jeff says. “I can’t even put it into words: Why now? Why this place?

“It was like a really weird closure.”

Another strange, daily reminder of their profound loss.

That night, Jeff went to bed early; he lost his own bid for a state representative seat. Lori stayed up, alone, awaiting the results on the amendment issue.

Four years earlier, she’d spent election night with Andrew, a joyous occasion when the two celebrated Obama’s victory. Minnesota had tried then to amend the Constitution to add a sales tax to help wildlife causes. Andrew told family members: “Oh, no, you don’t want to do that. You hardly ever want to amend the Constitution!”

That conversation kept going through her mind this election night. Finally, in the wee hours Wednesday, came the news: The Constitution would not be amended to limit marriage.

It was a victory Andrew would embrace.

“His life was very meaningful, and I feel like now in death, there is meaning in that, too,” she says. “Before, it would have been our grief to bear as a family and that would have been it. Now, his name is out there and he will be associated with a movement and a change, and I think that’s quite a legacy.”

Their son, although a soldier, was a peace activist, too. He had a favorite saying: “You can make change in the smallest of ways just by being nice to somebody.”

At least for now, Mom and Dad can rest. Change has arrived.