Story highlights

CDC: One in 88 U.S. kids is thought to be autistic

Joseph Sheppard, 42, is a person with autism who works on autism research

He runs an autism writing group in Victoria, British Columbia

Joseph Sheppard has an IQ above 130. Ask him about his life or worldview and he’ll start drawing connections to cosmology and quantum mechanics. He’ll toss around names of great intellectuals – Nietzsche, Spinoza – as if they’re as culturally relevant as Justin Bieber.

It might not be obvious that Sheppard has a hard time with small tasks that most of us take for granted – washing dishes, sending packages, filling out online forms. Or that he finds it challenging to break out of routines, or to say something appropriate at meaningful moments.

Sheppard, 42, has high-functioning autism. He found out only about six years ago, but the diagnosis explained the odd patterns of behavior and speech that he’d struggled with throughout his life. And it gave him the impetus to reinvent himself as an autism advocate.

“I was invisible until I found my inner splendor,” he told me in one of many long, philosophical, reflective e-mails earlier this year. “My ability to interpret and alter my throughput of judgments, feelings, memories, plans, facts, perceptions, etc., and imprint them all with what I chose to be and chose to do.

“What I choose to do is change the course of the future for persons with autism, because I believe in them and I believe, given the right support and environment, they will be a strong force in repairing the world.”

U.S. health authorities announced in March that autism is more common than previously thought. About 1 in 88 children in the United States have an autism spectrum disorder, according to the report. Autism spectrum disorders are developmental conditions associated with impaired social communication and repetitive behaviors or fixated interests.

Early therapy can change brains of kids with autism

Diagnoses have risen 78% since 2000, partly because of greater awareness, and partly for reasons entirely unknown. Most medications don’t help, and while some find improvements with intense (and expensive) behavioral therapy, there is no cure.

Rates appear to be similar in adults. England’s National Health Service found in 2009 that about 1 in 100 adults are on the autism spectrum. People with more severe forms of autism may not be able to live independently or hold complex, social jobs. But those considered high-functioning can have a wide range of careers; you may even have a classmate or coworker with high-functioning autism who isn’t as vocal about it as Sheppard, or who never got a diagnosis.

For World Autism Awareness Day in April, when organizations hold fundraising and awareness events to get the word out, Sheppard gave a talk at a local mental health facility about assisting people with autism in his idyllic Vancouver Island city of Victoria, British Columbia.

“The stigma environment is huge,” Sheppard told me in February over sushi at the University of Victoria’s cafeteria. “People can learn that you have autism and they can talk to you differently, they can treat you differently; you can feel like you’re less than human, your voice doesn’t matter.”

iReport: The invisibles: Autistic adults

Giving voice to people with autism

Sheppard found out he had autism after a relative’s diagnosis spurred him to get tested himself. His own diagnosis inspired him to help others. But to become fully involved and do his own research, he needed to return to school.

“I did a psychology degree in some ways to heal myself, and to bring myself into a higher level of functioning,” he said. “I had a real yearning to contribute to my maximum potential.”

In 2007, he went back to the University of Victoria – where he’d studied philosophy in the 1990s – for a second bachelor’s degree. He hopes to attend graduate school.

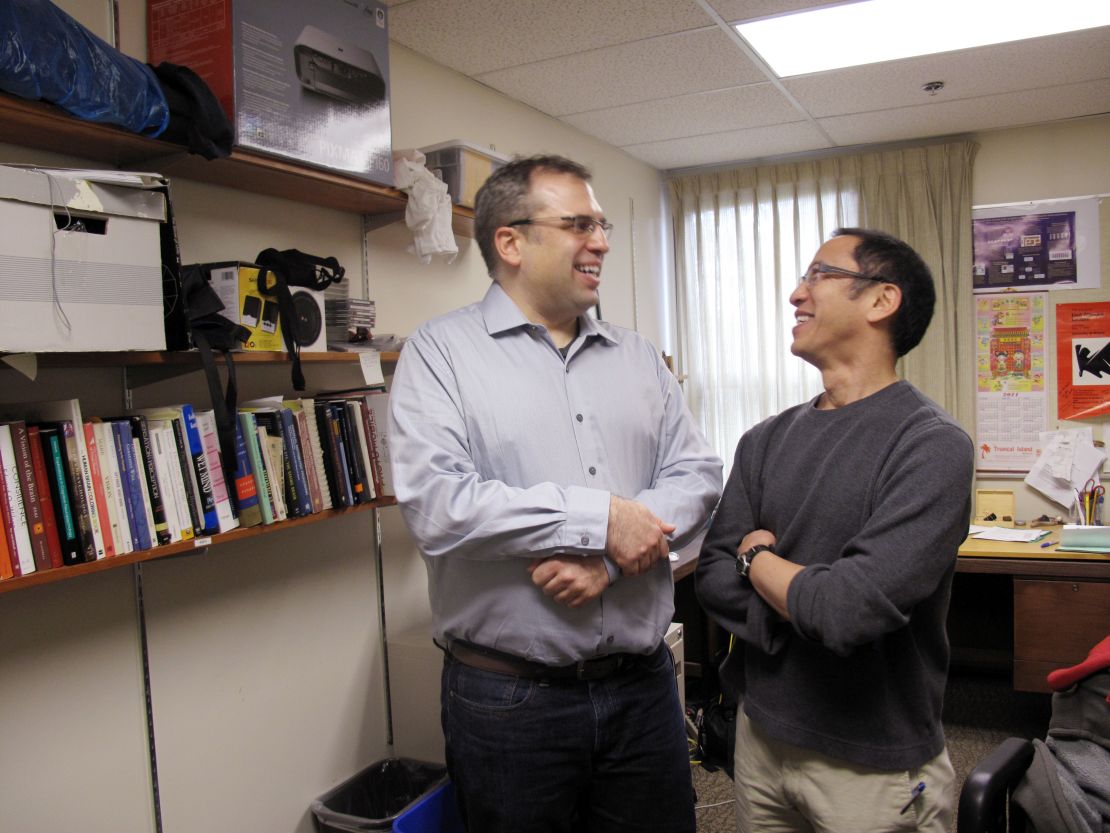

Last year, one of Sheppard’s advisers, psychology professor Jim Tanaka, brought him on as co-director of the Centre for Autism Research, Technology and Education (CARTe), which launched officially in November. The center uses technology to help people with autism.

“We have this dream of making UVic the destination campus for people on the spectrum,” Tanaka said. He and Sheppard want to actively recruit the emerging generation of young adults with autism who are applying to universities and help them thrive on campus.

Already, Sheppard and Tanaka are working with university students and children in Victoria who’ve been diagnosed with autism.

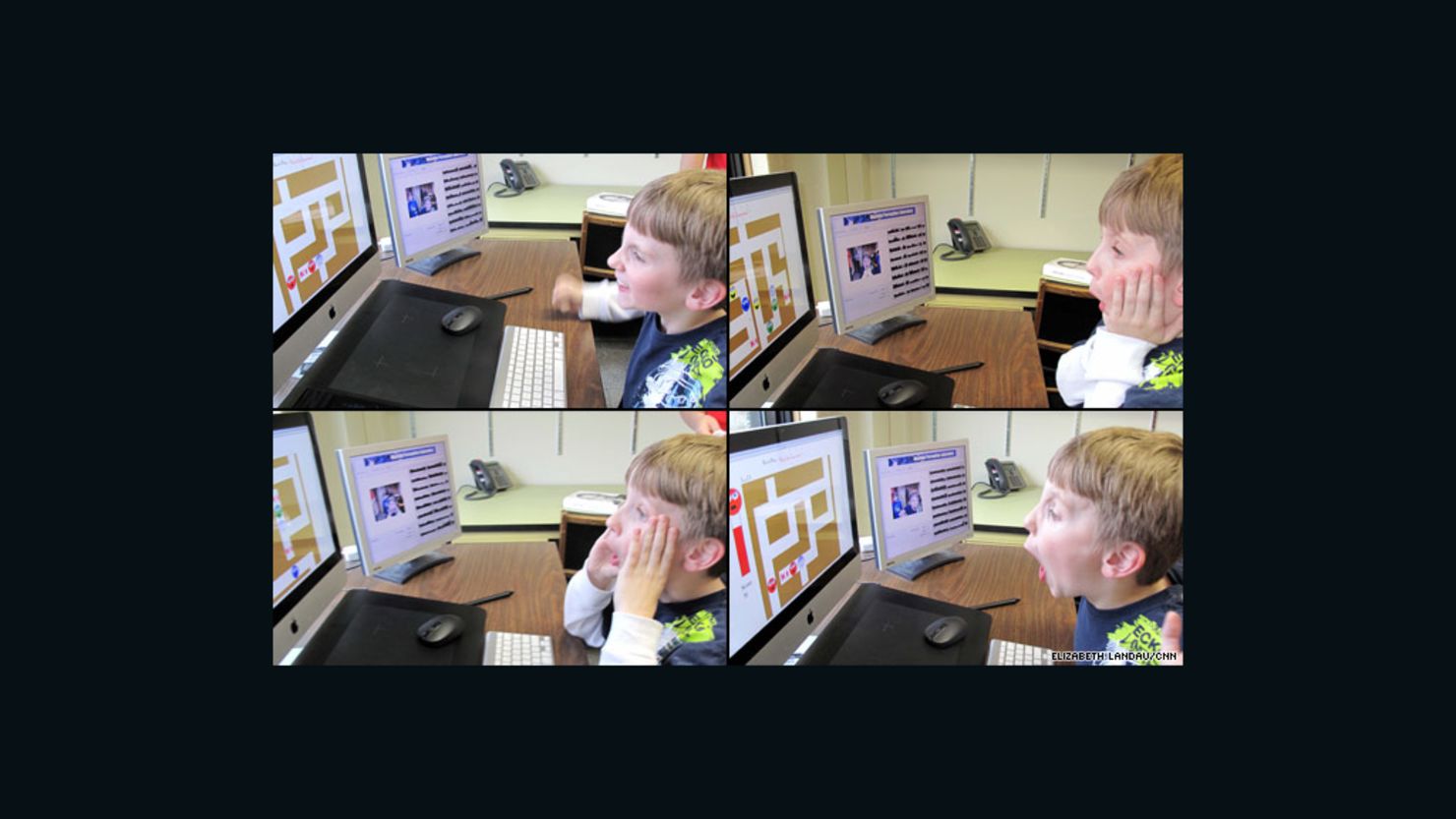

Their center is currently testing computer games Tanaka and colleagues at the University of California, San Diego developed, targeted at kids on the autism spectrum who need help recognizing and interpreting facial expressions.

In a game called FaceMaze, kids are challenged to mimic circle-shaped cartoon characters’ facial expressions on a computer screen. Another program is in development for the iPad that will feature short videos of people a child knows making different expressions.

The philosophy behind these games, Tanaka said, is that “if you’re better at expressing emotions, you’re better at perceiving them.”

The games appear to have some benefits – the quality of the kids’ facial expressions is improving, Tanaka said – but the research is still preliminary, and it remains to be seen if it will have an effect on everyday interactions.

Games like these are tested on weekends in a program called Face Camp.

On a recent weekend, they hosted about 20 kids on the autism spectrum at a middle school. Sheppard tried out an idea he had called Emotion Roller Coaster. He invited the kids to board an imaginary roller coaster that zoomed up and down the hallways. At each stop, one of Tanaka’s psychology students would prompt them to tell stories related to particular emotions. “The kids were just loving it,” Tanaka said.

“He’s the visionary of our center, and I just try to make it happen,” Tanaka added.

One of Sheppard’s big projects is to start a publication consisting entirely of fiction and nonfiction stories about autism by persons with autism. “Autism’s Own Journal” is aimed at helping people understand the subjective experience of having autism. According to its website, the inaugural issue will be published in April 2013.

The journal would be the work of a group Sheppard runs called Authors with Autism, where people on the autism spectrum can meet, talk and write together, “to take the power of their own kind of freedom and put down on paper what their needs and desires really are,” Sheppard says.

Sheppard developed a format for the group in which each person gets three minutes to share something related to writing or autism. Between sharings, everyone writes whatever they want for five minutes. About eight or nine people are involved; some are students at the University of Victoria. One of them, Philip, has made friends with almost everyone in the group.

“Joseph acts as a facilitator, and he encourages us to be our own leaders, and that gives us a lot of potential for individual expression,” said Philip, who asked that his last name be withheld.

At one of the first sessions this winter, during a sharing segment, a friend of one of the participants poked his head in, and the conversation stopped, Sheppard recalls.

“I think there’s just this judgment that happens whenever there’s a neurotypical in the room,” Tanaka explains, using the autism community’s term for someone who doesn’t have a neurological disability. “Part of the magic that’s happening is because neurotypicals are not allowed.”

iReport: I always knew he was special

A way of seeing the world

I met Sheppard and Tanaka at the University of Victoria during the week of an international science event in Vancouver in February. I had learned about their work from a contact at the university. Victoria is only accessible by air or water, so I took a sea plane to the quaint island port.

Towering over Tanaka at about 6 feet tall, Sheppard has imposing broad shoulders and large hands, but his demeanor is warm and considerate. His friendly hazel-green eyes don’t give away that he’s conscientiously trained himself to make eye contact during conversations, or that it still doesn’t come naturally.

Sheppard speaks passionately about autism and the need for more support. And in bolstering his arguments, he’s exceptionally thorough. For our first conversation, he had prepared a stack of dozens of peer-reviewed articles about autism to back up the facts that he planned to mention, so I wouldn’t have to take his word for it.

In March, we corresponded by e-mail, partly for efficiency, and partly because I quickly realized how well Sheppard expresses himself in writing, and that he had a lot to say in response to simple questions. And while a single article could not contain most of his copious reflections that flooded my inbox, he maintained a certain self-consciousness and humor about it. He titled one e-mail thread with the subject, “Could the man with autism I am interviewing be sending yet more long e-mails?”

Sheppard expresses his view of autism through science and science fiction metaphors. He’s writing a sci-fi-like book that attempts to articulate what autism feels like. Creating an alternate vision of the world helps Sheppard make sense of everyday relationships that might otherwise confuse him.

“The way I experience the world is so different that I have to learn how other people experience the world and talk in that language,” he told me.

To begin with, he views his body as a spaceship. He doesn’t fully understand the mechanics of that spaceship, so he reads a lot about science, and studies it, to try to learn more.

And, in his view, each spaceship – every person – has a different central computer delivering judgments about the spaceship’s mission and what it encounters, much like HAL in “2001: A Space Odyssey.” Sometimes, he says, those judgments make other people unkind to those with autism because they seem different.

Judaism also has informed his perception of the world and himself. (He’s writing a book called “The Dharma-Torah: Autism Space Flight Manual,” and friends call him by his Hebrew name Yossi). Sheppard did not grow up observant, but he has some Jewish heritage, and in the past seven years he has become an active member of the Orthodox Jewish community of Victoria.

He believes the religion’s rituals – the wrapping of teffilin, the prayers, the observance of the Sabbath – have given him a regimented routine that helped him overcome certain autism-related behaviors, such as repeatedly playing the same level of a computer game to the point that his work suffered. “Before I practiced Judaism, it was like all the rituals of the world crashed in on me and I could not move as a consequence,” he said in an e-mail.

Adults with high-functioning autism typically have difficulties perceiving the nuances of speech and behavior – for instance, friends say Sheppard often misses sarcasm and takes some phrases too literally.

And Sheppard has other day-to-day challenges, such as filling out online forms. “Sometimes I forget about that because Joseph is such an exceptional person,” Tanaka says.

Tanaka has helped Sheppard fill out online applications for scholarships and funding. Beyond the name and address fields, categories such as “subject area of study” don’t immediately make sense to Sheppard. It’s like “trying to fill out an IRS form when you have no clue what the questions are,” Tanaka explains. Meeting deadlines is also a challenge for Sheppard, who can talk or write on and on in long “monologues” about particular subjects.

Jacqueline Bush, a graduate student at the University of Victoria who tutored Sheppard in statistics, found him extremely bright and quickly realized he didn’t really need tutoring– only structure. They’ve stayed good friends, in part because of Sheppard’s spontaneity and “contagious” excitement about life, she said.

“He’s an incredibly genuine person with a real passion to help everybody,” Tanaka said.

Journey to diagnosis

Sheppard’s family moved around a lot when he was a child: England, Peru, Boston, New Mexico, British Columbia. His parents owned stores that sold sacred objects from all over the world, he said.

He remembers that whenever his father was cross with him, his father always thought Sheppard was smirking, and as a boy he had trouble telling his father how he felt. His friends were stuffed bears: Beary and Mary were a couple, who were also friends with Larry, Terry, Jerry and Gary. Typical of his ability to see patterns, he notes that, today, his rabbi’s name is Harry, and the name of his ex-common-law wife rhymes with Beary.

After studying philosophy in the 1990s, Sheppard became a professional event planner in Victoria, organizing everything from hip-hop concerts to fashion shows to go-kart races to the 1997 North American Indigenous Games. As an independent contractor, he didn’t have to keep to anyone else’s schedule. He would work anywhere from about 20 to 60 hours a week, at any time of day or night. What others consider a “normal” 40-hour workweek is an impediment for Sheppard: “Keeping myself on the schedule becomes my focus and accomplishment, not creating something that is super successful.”

Sheppard later taught life-coaching workshops in Arizona. But after the 2000 burst of the dot-com bubble and the World Trade Center attacks of 2001, Sheppard found that people were less open to innovative, quirky ideas and more concerned about money. He delved deeper into his reading and writing, and homeschooled his children for 3 1/2 years.

By 2005, Sheppard was unemployed and physically ill. He had untreated asthma, Celiac disease, sleep apnea and migraines.

Around that time, a young relative he didn’t want to identify was not speaking in full sentences at the appropriate age. Sheppard talked about it with a school principal he knew, who suggested the child get tested for autism. A team of specialists evaluated the child and arrived at a diagnosis of autism.

After Sheppard read that autism can run in families, some of his odd behaviors and challenges fell into place.

“Suddenly my past started making sense in ways I cannot describe. I then decided to be brave like my relative and accept being tested,” he wrote in an e-mail. In 2006, he underwent about eight hours of tests, which helped a clinical psychologist conclude that Sheppard had high-functioning autism.

“He was able to look back on his life and make sense of a lot of things,” Bush said. “For sure, I think he felt that getting that diagnosis was very helpful in understanding how he’s different.”

Within a year of the diagnosis, Sheppard’s relationship with his common-law wife underwent a steep decline, and they ended it a year and a half later. Their three children don’t live with Sheppard, but he still sees them.

“I do not blame the diagnoses or my ex or myself” for the end of the relationship, Sheppard wrote in an e-mail. “My illnesses had something to do with it I think, I just was not functioning properly, and a family most often needs parents that can function fully.”

Later-in-life diagnoses of autism are not uncommon, says Leslie Speer, clinical psychologist at the Cleveland Clinic Center for Autism in Cleveland, Ohio. While doing autism evaluations in Salt Lake City, where she got her doctorate, she identified many adults as having high-functioning autism in their 30s, 40s and 50s.

“The individuals I met, they were often depressed,” Speer said. “They couldn’t understand why they had so many difficulties in their social relationships, why their wife had left them and why they couldn’t keep down a job.”

Some of these patients took comfort in knowing there’s a name for the problems they’d been having, a community of others who share those difficulties and counseling resources available, Speer said.

Autism as an identity

Reflecting on his life, Sheppard noted that it may seem to an outsider as though he suddenly emerged from obscurity since his diagnosis. And in a way, he did – after finding an identity as a person with autism, he suddenly had a mission and purpose.

–Not look at objects when another person points to them

–Avoid eye contact and want to be alone

–Prefer not to be held or cuddled or might cuddle only when they want to

–Appear to be unaware when other people talk to them but respond to other sounds

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

One issue of identity that troubles him and others in the autism community involves a proposed change in the next edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the essential guidebook for mental health professionals.

The DSM-5, to be published in May 2013, will no longer include a separate diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome, which is basically high-functioning autism without any childhood delay in cognitive or language development.

Many experts, including Speer, say the majority of people who meet current autism spectrum disorder criteria would still qualify for services under the revised definition.

But Sheppard remains concerned that the changes will become an excuse to limit diagnoses and support for individuals with high-functioning autism, as well as those who aren’t able to correctly describe their autism-related behaviors. He supports the conclusions that science backs up but also recognizes that a deeper identity issue is at play when it comes to autism.

“Autism identity is something different than the condition,” he said. “Just like gender is not the same as biological sex. And, so, if someone … is identified through Asperger’s, then I think that if it’s important to them it should be recognized.”

For instance, his friend Philip, who attends Sheppard’s writing group, identifies as having Asperger’s syndrome specifically, while Sheppard does not. But Philip recognizes that he and Sheppard, while having individual strengths and weaknesses, are in similar places on the autism spectrum. And they share a passion for helping others with autism.

“His goals with helping autistic individuals transition from high school to university, or from university to the work force, that’s what really matters to me,” Philip said.

Toward a better future for people with autism

Sheppard has big dreams, but the reality is there are plenty of people with more severe autism who won’t get to university. It’s a big issue as to what happens when they are no longer legally eligible for educational services in the United States – it’s generally age 22, but varies by state.

Some go to a workshop setting where they get paid minimally to do work, said Dr. Max Wiznitzer, a pediatric neurologist and autism expert at Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital in Cleveland. Others find appropriate part-time work such as cleaning, shelf-stocking and grocery-bagging. Sometimes, it’s glorified daycare.

Some sit at home because there aren’t any real opportunities in their community, or their parents are concerned someone will abuse or take advantage of them.

“The idea is to make sure that they don’t have to sit in front of a TV all day,” Wiznitzer said. “But it is an issue in terms of making sure that they have some opportunities for gainful employment at their developmental levels.”

In Canada, where Sheppard lives, the availability of government-funded services and programs for autism varies widely according to province, and sometimes there are significant waiting lists. Such resources are even more limited for older children and adults, according to Autism Speaks Canada.

As a person with autism himself, Sheppard approaches low-functioning individuals as “valued elders” – they are wise but need to be cared for and are not expected to go full speed through life, he said. In his vision of helping these people, Sheppard doesn’t want to change people with autism, but rather provide better support for them, and allow them to thrive.

“He brings out the best in the people,” Philip said. “He makes them feel like a winner.”

Such optimism is greatly needed as autism gets diagnosed ever more frequently. Many parents struggle financially and emotionally to support their children on the autism spectrum, hoping they grow up to live independently and have meaningful careers – but it doesn’t always happen.

In the face of stigma, bureaucracy and ignorance, the community needs a guide to help people see the good in themselves and reach their own potentials – in a word, a shepherd.